The 1918 influenza pandemic – often called the “Spanish flu” although it did not originate in Spain – killed more than 50 million people globally and about 675,000 in the US.

“The intensity and speed with which it struck were almost unimaginable — infecting one-third of the Earth’s population,” the World Health Organization said.

Fast-forward to 2020, the coronavirus is also spreading with astonishing speed as officials and medical experts grapple with how to slow the virus and keep people safe.

Some of the painful lessons learned from the 1918 pandemic are still relevant today and could help prevent an equally catastrophic outcome.

Here’s what we could learn from the past:

Lesson #1: Don’t let up on social distancing too soon

During the Spanish flu pandemic, people stopped distancing too early, leading to a second wave of infections that was deadlier than the first, epidemiologists say.

“The image that we have of this epidemic curve, we say we’re going to reach a ‘peak’ — we look at it, it looks like Mt. Fuji in our minds … a single, solitary mountain,” epidemiologist Dr. Larry Brilliant said.

“I don’t think it’s going to look like that. I think a better image is a wave of a tsunami, with echoed waves that follow. And it’s up to us, how big those other waves will be,” he added.

Lesson #2: Young, healthy adults can be victims of their strong immune systems

Young, healthy people are not invincible and their strong immune systems might work against them.

“In those cases, it is not an aged or weakened immune system that is the problem — it is one that works too well,” CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta said.

“In some young, healthy people, a very reactive immune system could lead to a massive inflammatory storm that could overwhelm the lungs and other organs,” he added.

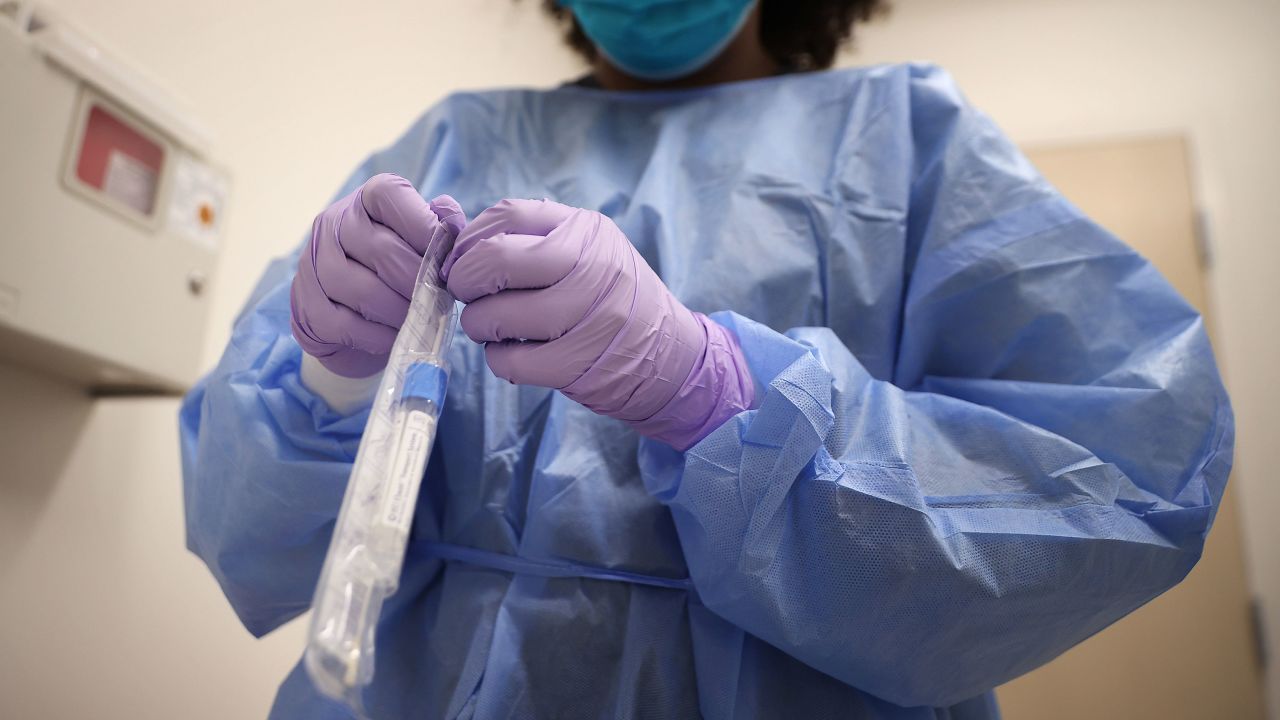

Lesson #3: Don’t throw unproven drugs at the virus

The Spanish flu and the novel coronavirus pandemics share two major challenges: the lack of a vaccine and the lack of a cure.

Back in 1918, remedies “varied from the newly developed drugs to oils and herbs,” according to a Stanford University research post.

“The therapy was much less scientific than the diagnostics, as the drugs had no clear explanatory theory of action,” the post said.

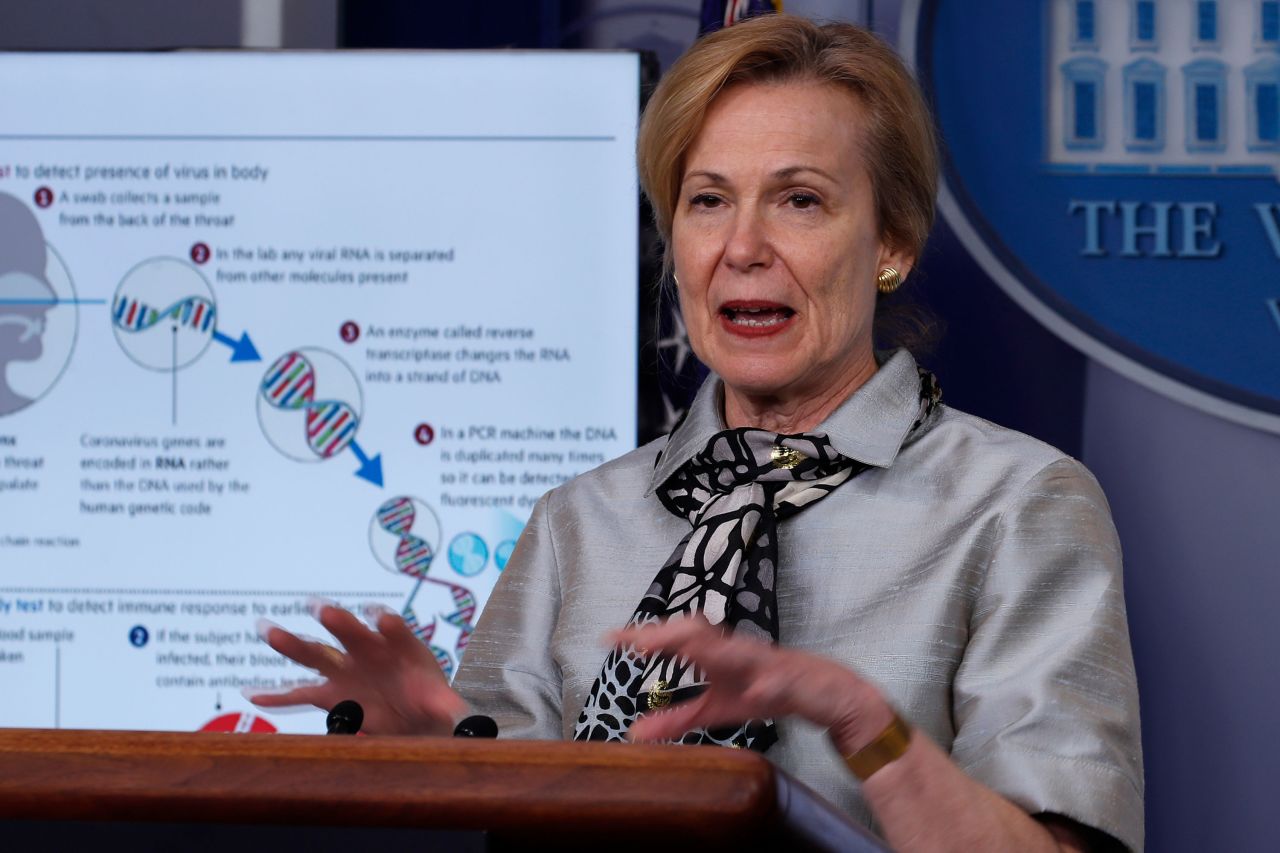

In 2020, there is widespread speculation about whether hydroxychloroquine – a drug used to treat malaria, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis – could help coronavirus patients.

The bottom line: It’s still not clear whether some drugs will cause more harm than good in the fight against coronavirus.