Editor’s Note: This CNN Travel series is, or was, sponsored by the country it highlights. CNN retains full editorial control over subject matter, reporting and frequency of the articles and videos within the sponsorship, in compliance with our policy.

The Qatari desert is home to rolling sand dunes and dramatic limestone cliffs – and lately, to otherworldly art installations.

About an hour’s drive north of colossal monolithic sculptures installed by US artist Richard Serra, the rock formations and desert plants dotting the remote landscape give way to a cluster of striking twisted structures.

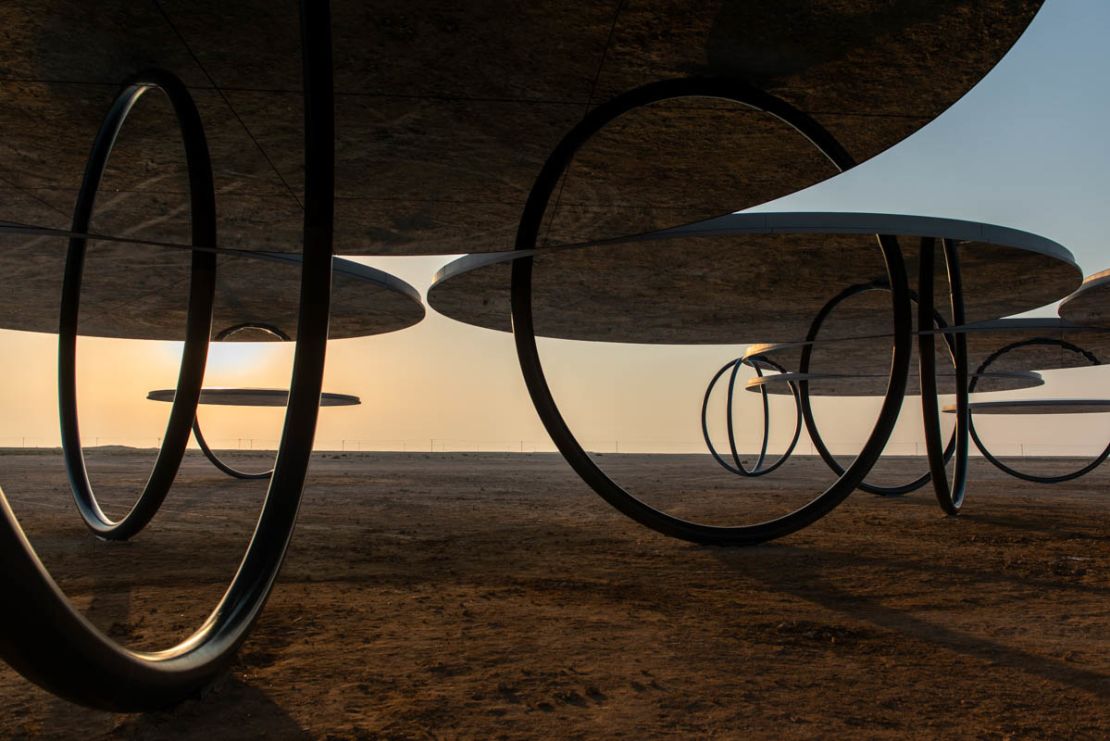

These free-standing rings and silvered-glass mirrors are the work of Olafur Eliasson, an Icelandic-Danish artist known for his exploration of humanity’s deep-rooted connection to nature.

Titled “Shadows Travelling on the Sea of the Day,” the artwork was installed in 2022 in northwestern Qatar. It comprises 20 large circular shelters, three single rings and two double rings that are placed according to the axes of a fivefold symmetrical pattern.

Up close, the geometric shapes seem both grandiose and in harmony with the infinite horizon.

The mirror ceilings playfully blend the boundaries between the sandy ground and the vast sky, while the interaction of sunlight and shadows streaming through the pavilion creates continuously changing panoramas.

Eliasson, who lives and works in Copenhagen and Berlin, says he was drawn to this remote corner of Qatar by its surprising similarities to the terrain of his family’s windswept homelands in the North Atlantic.

The Iceland connection

Despite the appearance of barren desert, he said he was also amazed by the discoveries he made there.

“When I first visited Qatar, it struck me that it is in a sense not unlike Iceland, which I know well, since my parents are from there,” Eliasson tells CNN. “It has these vast landscapes that appear to be at the periphery of the inhabitable.

“Upon closer inspection, of course, they are teeming with life, but to the uninformed viewer, the desert can appear blank, monolithic.”

He says his work documenting the repeating patterns of Iceland’s rivers, caves and hiking shelters gave him a perspective on Qatar that drew him away from the gleaming new skyscrapers of its capital city, Doha.

“I felt very drawn to the Qatari landscape and viewed the country through various lenses: the environmental and geological history of the land, which stands out in stark contrast to the phenomenal new architectural projects,” he says. “I am fascinated by these contrasts.”

While Eliasson is known for blockbuster artworks like his Weather Project, which bathed London’s Tate Modern Gallery in the orange light of a giant mirrored sun, his Qatar work is located in such an empty spot that it won’t enjoy quite the same audience numbers.

“It is reached by driving through the rugged desert northwards from Doha, past Fort Zubarah and the village of Ain Mohammed.

“To visit the work, you have to make some effort.”

Above and below

Although the location is devoid of significant historic landmarks or topographical features such as mountains or valleys, Eliasson says the artwork can help transform visitors’ perceptions of it.

“The artwork, its mirrors and structure invites you to see the landscape anew, the location you may take for granted as plain, empty, or everyday, and hopefully it will offer you a new relationship to the ground beneath your feet and to the earth.”

Eliasson says the structures are designed to draw people in, to interact with the installation and to encourage them to contemplate their surroundings.

“From a distance, the mirrored undersides of the cluster of circular shelters and free-standing rings can be seen shimmering on the horizon,” he says. “Up close, you see how the half-pipes are reflected in the mirrors and become full circles.

“This creates a kind of environment that wraps around you in all directions when you stand among the structures. The mirrors reflect the land below and they reflect you within this landscape, and you are entangled with it, so to speak.”

Human movements, says Eliasson, are amplified by the reflections.

“All the while, as the sun moves across the sky, the cool, hospitable shadows travel across the sandy ground and color of the soil reflected above and around you. In the ceilings fitted with large mirrors, you may also – with the right amount of patience – detect these cyclical journeys.

“Looking up, you come to realize that you are, in fact, looking down – at the Earth and at yourself. Above and below, sand envelops you, together with anyone else sharing the space.”

Reality check

Eliasson recommends waving a foot or arm when beneath the mirrors to enhance the experience.

“It is a kind of reality check of your connectedness to the ground. You are at once standing firmly on the sand and hanging, head down, from a ground that is far above you. You will probably switch back and forth between a first-person perspective and a destabilizing, third-person point of view of yourself.

“This oscillation of the gaze, together with the movement of your body, amplifies your sense of presence, while the curving structures seem to vanish into the surroundings, dematerializing and becoming landscape.”

The artist says his work is intended to create a sense of passing time and of disconnecting from our standard perception of time.

It’s also, he hopes, a way to fire up imaginations – perhaps to contemplate different ways of living to help alleviate the climate crisis which, he says, art should play a key role in tackling.

“Unlike climate activism, for instance, art is often slow and circuitous. I see ‘Shadows Travelling on the Sea of the Day’ as inviting reflection on how we can rebuild relationships with the planet; how we can create new narratives for transitioning to different ways of being on and caring for Earth.

“It offers embodied experiences and space for self-reflection while providing an opportunity to share one’s experiences with others across communities and cultures.”