Picture something extremely British. Now double it. Did you imagine the Beatles, striding across Abbey Road — the twist being that their classic album cover is rendered in the contents of a full English breakfast?

In 2012, food artist Paul Baker cooked up this exact scene. John is the (scrambled) eggman, while vegetarian Paul is tastefully made out of mushrooms. Abbey Road is re-surfaced in baked beans, a bacon Volkswagen Beetle pulled up on the side. Slabs of white and brown toast form the marked crosswalk.

In one fell swoop of edible absurdism, Baker’s artwork demonstrates the cultural heft of the full English breakfast. Devoured in the nation’s “greasy spoon” cafes and motorway stop-offs — not to mention some of its ritziest hotels and restaurants — this gut-busting symphony of bacon, eggs, sausage and various other cooked ingredients (invariably sluiced down with a steaming cup of tea or coffee) has become shorthand for Britishness.

It is as big as the Beatles, bigger. Like “Abbey Road” itself, the full English — or “fry-up” or “full monty” or “cooked breakfast” — is both revered as a thing of godlike genius, and has its sour-faced critics; those who claim it is too chaotic, too self-indulgent for its own good.

So where did the full English originate? How did it come to define a nation? And come to think of it, what exactly is it?

The evolution of the full English breakfast

English Breakfast

Historically, English breakfasts were a modest affair. For Britain’s Roman invaders, it was the least important meal of the day. Its medieval Norman conquerors were happy starting the morning with a hunk of bread and a slurp of weak ale.

It’s true that meat was sometimes eaten first thing (in 1662, diarist Samuel Pepys recorded “a breakfast of cold roast beef”) but the genesis of the fry-up wasn’t really sparked until the Victorians came along. As Kaori O’Connor writes in “The English Breakfast,” “Large breakfasts do not figure in English life or cookbooks until the nineteenth century, when they appear with dramatic suddenness.”

It was in the grand houses on country estates that these languorous, buffet-style breakfasts made their debut — the kind depicted in shows like the Edwardian-era “Downton Abbey”, where diners help themselves to hot viands piled high in silver chafing dishes.

Aristocratic socialite and writer Lady Cynthia Asquith recalled breakfasts with “crisp, curly bacon, eggs (poached, boiled and fried), mounds of damp kedgeree (made with salmon), haddocks swimming in melted butter, sputtering sausages and ruddily exuding kidneys.”

As well as being an indulgent display of wealth, writes O’Connor, the English breakfast was a robustly patriotic retort to the hors d’oeuvres-loving French: “There were no such things as a French breakfast… So breakfast time became the bastion of Englishness, and breakfast emerged as the national meal.”

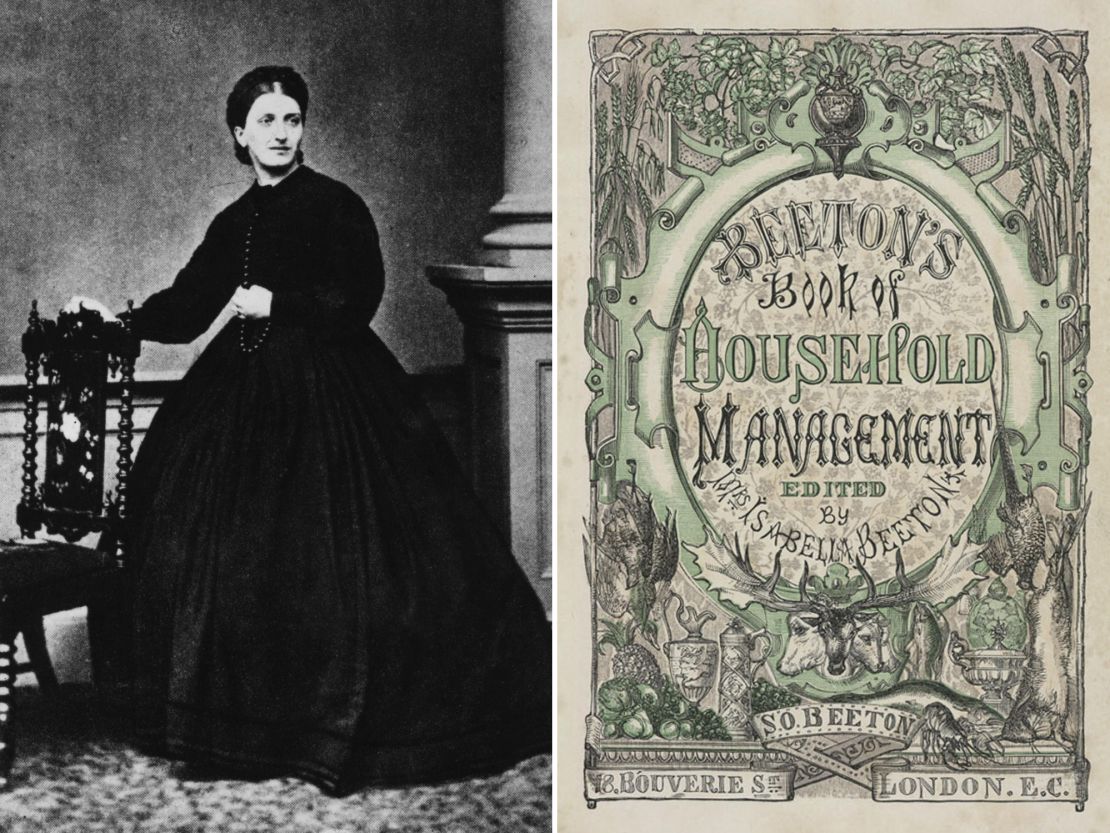

The middle classes soon cottoned on, encouraged by celebrity cook and domestic goddess Isabella Beeton. In 1861 Beeton published her “Book of Household Management,” which featured recipes for breakfast dishes including “fried ham and eggs” and “broiled rashers of bacon.”

A trend soon emerged in the publishing world: “The Breakfast Book” (1865), “Handbook for the Breakfast Table” (1873), “Breakfast and Luncheon at Home” (1880), “Breakfast Dishes for Every Morning of Three Months” (1884). In 1874, the Edinburgh Evening News wrote of “An English Farmer’s Breakfast,” consisting of rashers of bacon “bubbling with grease and laid on thick slices of bread.”

Other publications from the time carried ads for bacon and sausages. “For first-class breakfast bacon,” ran an ad in The Blyth Times in 1890, “try Thompson’s English rolled flitch.” By 1921, a Lady Jekyll was telling readers of The London Times that “no breakfast table is complete without eggs and bacon.”

What exactly is a full English breakfast?

It’s easier said than done to spell out what a full English is.

While various components (fish, marmalade, kidneys) gradually fell by the wayside, others were tacked on. Heinz beans — canned haricot beans in tomato sauce considered by many now to be an integral element of the fry-up — arrived in 1886, when the young entrepreneur Henry Heinz sold five cases to London department store Fortnum & Mason: “I think, Mr Heinz, we’ll take the lot!”

HP Sauce — a spicy brown ooze, its bottle emblazoned with the Houses of Parliament — registered its name in 1895, and has smothered sausages the length and breadth of the country ever since. The many nuances of the full English are best appreciated by gazing into the window of any given greasy spoon, where you’ll be greeted with variations along the lines of:

“Set 1: Egg, Bacon, Beans, Sausage, 2 Toast, Tea or Coffee

“Set 2: Egg, Tomato, Sausage, Mushroom, 2 Toast, Tea or Coffee

“Set 3: Egg, Bacon, Tomato, Sausage, Mushroom, Toast, Chips, Tea or Coffee…”

On and on it goes, like the workings of some brainiac trying to break a calorific Enigma code. The mapping of a fry-up becomes all the more convoluted when you take into account its Celtic cousins, the full Scottish (with the addition of haggis, and traditional sausages switched out for square Lorne sausage); the full Irish or Ulster fry (often featuring soda bread and white, rather than black, pudding); and the full Welsh (where leftfield laverbread and fresh cockles get a place at the table).

Even more confusingly, despite being called a fry-up, these days the ingredients are not necessarily fried.

At least some aspects of the breakfast are easier to pigeonhole. Sausage, bacon and egg are usually a given, as is some form of bread with which to mop up the residue. Black pudding (aka blood pudding, a favorite of the late Anthony Bourdain), mushrooms, tomatoes (fresh or tinned) and chips regularly feature, but tend to be the diner’s choice.

Every Brit has their own dream team of ingredients, their own thoughts on each ingredient realizing its full potential. Eggs might be fried, poached or scrambled. Bacon smoked or unsmoked. Bread could be fried, toasted, or left as is. A dollop of tomato ketchup or brown sauce may or may not adorn the side of the plate.

In the sitcom “I’m Alan Partridge,” the eponymous local radio host provides a pompous postmortem on his Ukrainian girlfriend’s stab at a cooked breakfast:

“Bacon, 10 on 10. Button mushrooms, bingo. Black pudding, snap. Minor criticism — more distance between the eggs and the beans. I may want to mix them but I want that to be my decision. Use the sausage as a breakwater. But I’m nitpicking. On the whole a very good effort. Seven on 10. Let’s make love.”

Some ingredients should be disqualified altogether, argues Guise Bule from the English Breakfast Society, a group of volunteers who celebrate the history and tradition of the English breakfast. “Reconstituted potato hash browns are a lazy replacement for bubble and squeak,” he announces, with the air of scientific fact. Onion rings are another component that have elbowed their way onto British breakfast plates in recent times, in a move that many traditionalists consider sacrilege.

One thing most fry-up lovers can agree on is that the breakfast should be heavy on the stomach, light on the wallet; something “Kitchen Nightmares” chef Gordon Ramsay is now painfully aware of since diners chided him for charging £19, or nearly $25, for what they perceived to be a particularly stingy spread.

Such accusations cannot be leveled at the Dalby Cafe in Margate, Kent, which went viral after local rock star Pete Doherty demolished its infamous “mega breakfast” in under 20 minutes, earning himself a place on the coveted wall of fame. And you thought biting the head off a bat was rock ‘n’ roll.

The fried breakfast today

Like most English inventions — the flush toilet, the iron bridge, the hovercraft — the fry-up has not always enjoyed an easy ride. World War II brought severe food rationing, a broadside that took the fry-up years to recover from.

Nonetheless, as mass-processed foods like sausages, battery-farmed eggs and sliced bread rocketed in the 1950s, the English breakfast became a national obsession. Any cafe or hotel worth its salt cooked one. Brits visiting the Spanish package vacation resorts of Benidorm and Majorca demanded eggs and bacon served beachside. In 1953, when thieves broke into a west London secondary school, they made time to fry themselves a few eggs and brew a pot of tea.

But in today’s age of kale smoothies and overnight oats, the iconic breakfast faces a fresh reckoning. “To eat well in England,” the playwright Somerset Maugham once said, “you should eat breakfast three times a day.” Yet recent research shows younger Britons are eating just two or three fry-ups a year. In an acutely health (and time) conscious society, some are beginning to ask if the full English is dying out.

If that is the case then British society is making a good job of hiding it. TV broadcasts constant reruns of “Four in a Bed,” a low-budget reality show in which bed-and-breakfast owners judge each other on the freshness of their duvets and the standard of their English breakfasts. Seaside resorts hawk miniature English breakfasts in hard candy form. On most high streets in the country you’ll find a branch of low-cost pub chain Wetherspoon slinging bacon, sausage and egg for as little as £2.99 a pop.

At the other end of the restaurant spectrum, where Gordon Ramsay flubbed his lines, others have got the memo. The Hawksmoor restaurant chain recently reinstated its redoutable take on an English breakfast following public outcry when it was briefly paused. “We’ve never been so inundated by requests to bring something back,” explains Huw Gott, one of Hawksmoor’s co-founders.

Every Saturday, Hawksmoor branches in London, Edinburgh and Liverpool pile up 50-80 plates with sugar-pit bacon chop, Victorian-style sausages, Moira black pudding, hash browns, grilled bone marrow, trotter baked beans, fried eggs, grilled mushrooms, roasted tomatoes, unlimited toast, and HP Sauce gravy. “Warning,” runs the breakfast’s tagline, “Not for the faint-hearted.”

Far from simply being a ritzy take on Dalby Cafe’s angina-inducing food challenge, Hawkmoor’s breakfast is a paean to the early days of the hearty English breakfast. “We use a recipe from the Victoria era for our sausages made with pork, beef and mutton with plenty of herbs and spices,” says Gott.

Elsewhere, the English breakfast continues to evolve, just as it always has. In April 2024, home appliance manufacturer Breville opened a “Grease-Less Spoon” pop-up, showing how ingredients could be cooked more healthily in an air fryer. Veggie and vegan options now appear on many breakfast menus. A brand established by Paul McCartney’s late wife, Linda, does a roaring trade in meat-free sausages, many of them ending up at the breakfast table.

Something else hints at the fry-up’s immortality; who’s ordering it.

“We have people from all over the world coming along hunting out a perfect British breakfast,” says Hawksmoor’s Huw Gott. Social media has ratcheted up this appreciation a notch or two.

On TikTok, Francophile twists are attempted on this most British of breakfasts. American food presenter Adam Richman of “Man Vs Food” fame recently traveled to Bury Market in the north of England to savor lumps of Chadwick’s famed black pudding.

The English breakfast was created as a statement piece, and in many ways it remains just that. A meaty calling card for Brits. A delicious tourist attraction. Something for foreigners to gawk at, sometimes bungle horrendously when they have a go at it themselves — but ultimately, relish and applaud.

So long as there’s tourism in Britain, you can be sure the fry-up will follow. Just as, while there are Brits vacationing in Benidorm, the scent of sizzling bacon will continue to waft along the esplanade.