She’s become one of the most passionate and fearless shark advocates in the world, but Valerie Taylor had little interest in the predators during her younger years.

The pioneering Australian diver left school at the age of 15 with the intention of becoming an animator, and says she would have chosen to work with tigers if she hadn’t “gotten to know sharks.”

In the years that followed, Taylor became so well acquainted with them that she famously appeared on the cover of National Geographic magazine with her arm in the mouth of a shark while wearing a chain mail suit in 1982.

However, she admits that getting comfortable around the apex predators was a “gradual thing,” as “certain species are much nicer to get to know than others.”

“You befriend a shark, just like you befriend a dog, you give it a treat,” she tells CNN Travel. “And it follows you around saying it wants another treat.”

Taylor’s relationship with sharks began in the 1950s, when she began spearfishing with her father, and was asked to join a local fishing club.

“In the old days, when you’d speared a fish, you frequently had a shark come and try to take your fish,” she explains. “So I got to know them to a certain extent.”

She began competing in various spearfishing championships during her 20s, beating out many of her male counterparts.

Underwater legend

It was at one of these contests that she met the man who would later become her husband, Ron Taylor, who was also a competitive spearfisher at the time, as well as an underwater filmmaker.

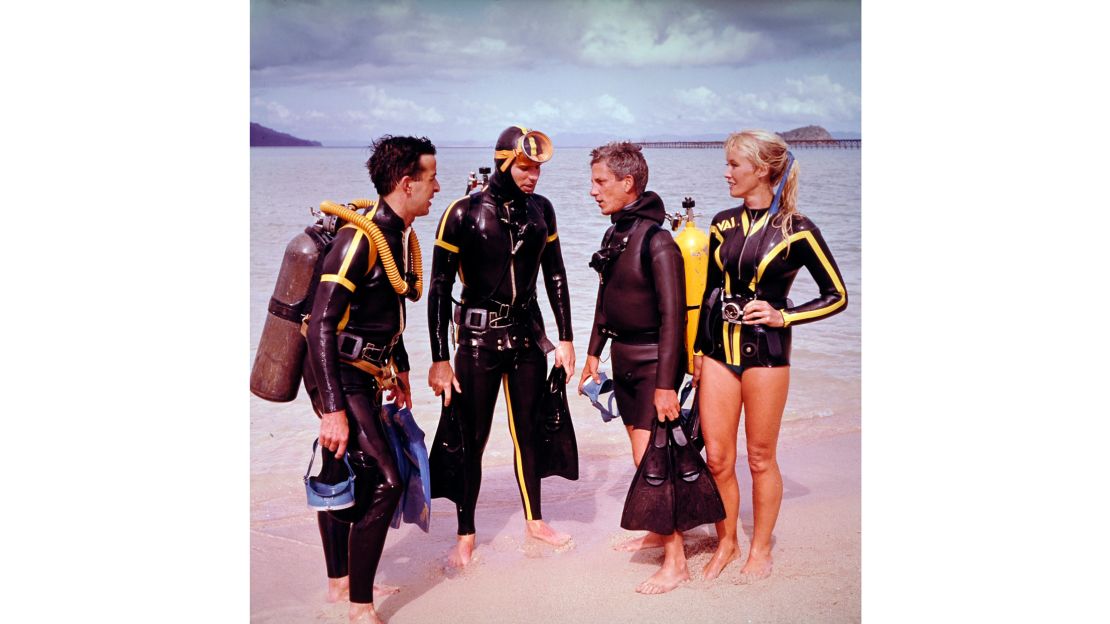

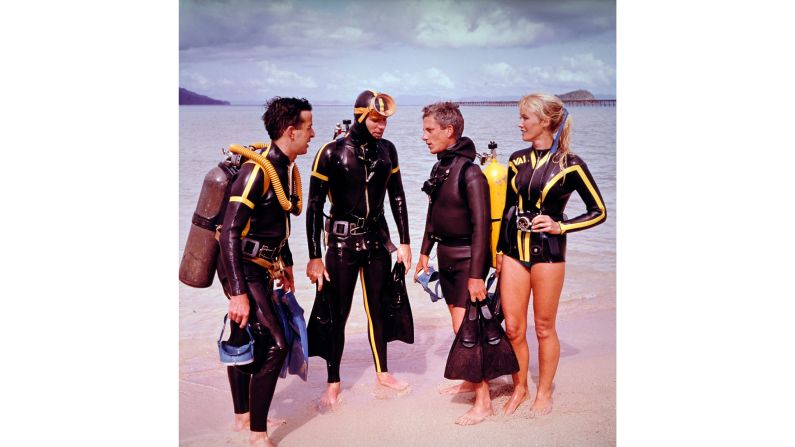

“I married Ron and he started filming me working with sharks, feeding them and playing around,” she says.

The couple quickly found that theaters and TV stations would pay good money for the footage, particularly if Taylor featured prominently.

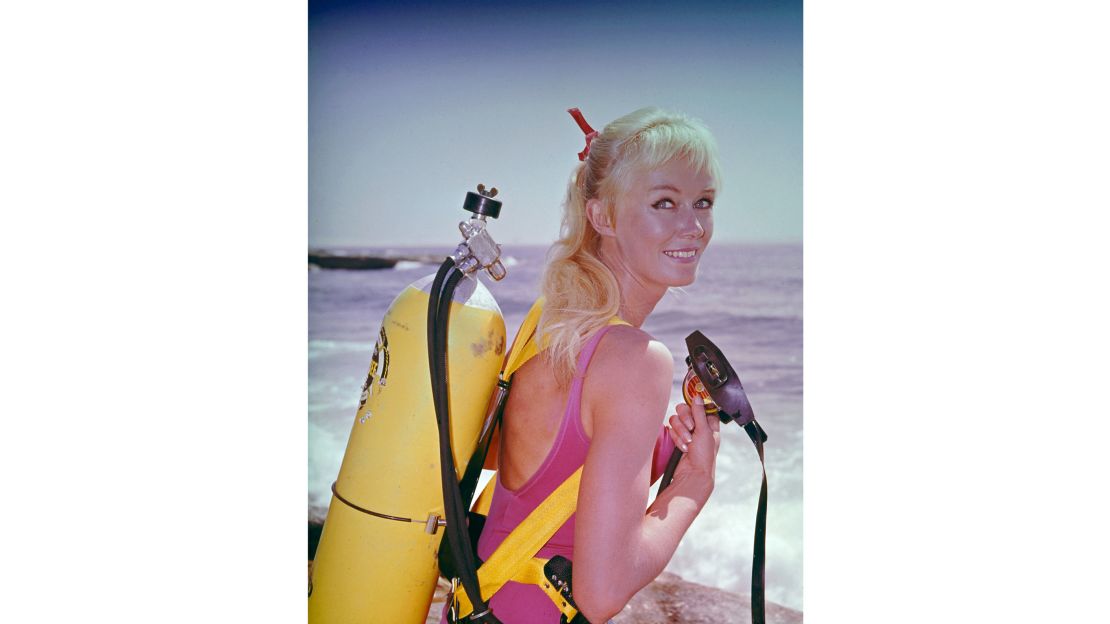

“We learned that if I swam around with the sharks in a bikini, it would sell better than if there was no person in the picture,” she explains.

“So every weekend, we’d be out on the water, trying to find sharks and film them. They weren’t interested in other marine animals. They were just interested in sharks. And we were trying to make a living.”

“In the beginning, we didn’t have a wet suit,” says Taylor. “We didn’t even have proper scuba gear. So we worked our way up all the years. And I can only say it was a great adventure.”

Her extraordinary life is the subject of a new documentary from National Geographic Films,”Playing With Sharks,” which includes incredible underwater footage taken by her husband.

“The first footage [from the documentary] was from when I was a child in New Zealand, filmed eight millimeter black and white, by my father,” she says.

“I’ve been filmed since I was 14 years old and I’ll be 86 in a few months. All those years, I’ve been on camera.”

In 1966, Ron Taylor shot the first ever film of a great white shark and his career quickly began to take off.

By then, both had quit spearfishing, opting to focus their attention on capturing marine life on camera rather then hunting fish for sport.

“I only ever killed one shark,” Taylor says of her spearfishing past in “Playing With Sharks,” which is directed by Sally Aitken. “I wish I hadn’t.”

In 1969, the documentary “Blue Water, White Death,” a collaboration with American director Peter Gimbel, gained the Taylor’s worldwide attention, and Hollywood soon came knocking.

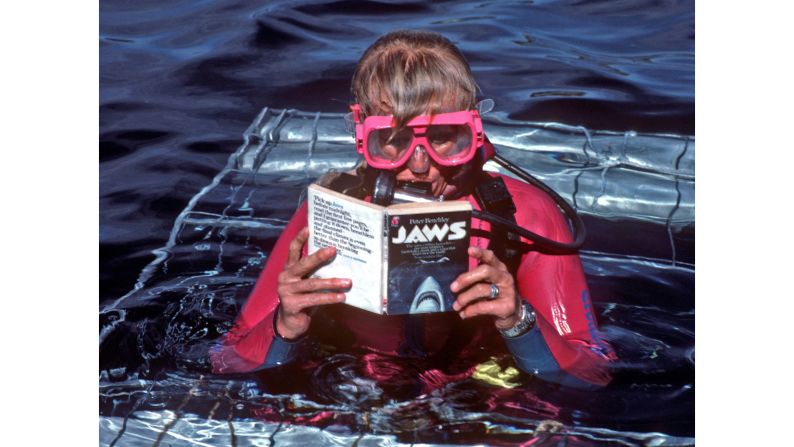

The couple were approached by producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown, who asked whether they thought that Peter Benchley’s novel “Jaws,” which centered around a shark that preys on a tiny resort town, would work as a movie.

“Of course we thought it would, because we could see work for ourselves,” says Taylor. “And the best way to make money in those days, and probably even now still, was working for Hollywood.”

After the producers purchased the rights to the book, they asked the pair to capture some live shark footage for the project.

The ‘Jaws’ effect

“You can’t direct a shark or a fish to do what you want,” explains Taylor. “It’ll do what it wants.”

They set off with a cage and a boat, in order to shoot the footage that would later be seen by millions of cinema goers across the world when “Jaws,” directed by Steven Spielberg, was released in 1975, generating $472 million at the box office.

“We had a bit of luck when the shark hit the side of the cage, broke it up and tore it off the side of the boat, winch and all,” she says.

“It [the boat] went tumbling to the bottom and Ron happened to be down there filming. They wrote that into the script.”

While they had a great time hanging out with the crew in the Massachusetts island of Martha’s Vineyard, where much of “Jaws” was filmed, Taylor admits both she and her husband were taken aback when they realized the impact the movie was having on the public’s perception of sharks.

“When the fuss broke out after the film was so successful, and people were so afraid, Universal [Pictures] sent Ron and I around America,” she says. “We did all sorts of talk shows, telling people not to be afraid.

“But it seems the average person likes to have a monster out there. And sadly, it’s a much maligned fish, the shark.”

Although she’s been bitten by sharks at least four times, Taylor insists she’s never felt afraid during any of her encounters with the predators.

“I was angry,” she says. “Fear is not a big thing with me. I was thinking, ‘Get away from me you brute. I knew not to pull away from the shark. I’ve very rarely felt afraid. My biggest fear is strong currents in the water.”

Taylor believes that the reason she’s always lived to tell the tale after having a shark sink its teeth into her skin is because she was able to remain still each time.

“If you stay really still when a shark grabs you and he realizes he’s made a mistake, he’ll let you go,” she says.

“The problem is, when something horrible happens, you always pull away. It’s an instinctive act. I’ve always stayed still, and the shark has let go.”

However, she does admit that one particular bite was “very, very bad.”

Problem of overfishing

“If you’re going to get bitten by a shark, make sure you’re working for Hollywood,” she jokes. “The surgeons are wonderful.”

For Taylor, one of the biggest misconceptions humans have about sharks is that they’re all dangerous.

“Out of several hundred species, there’s only about six or seven that are potentially dangerous,” she notes.

National Geographic estimates that humans have a one in 3.7 million chance of being killed by a shark. In fact, it’s actually sharks that are highly at risk.

A study published by British weekly scientific journal Nature earlier this year indicated that global oceanic shark and ray populations had declined by over 70% between 1970 and 2018.

Overfishing was cited as the main source for the decline, with around 273 million sharks killed every year.

Taylor has been very vocal about the impact of overfishing and points out that most of the sharks she and her husband caught on camera are no longer around.

“I’ve stopped seeing them when I go in the water,” she says. “Once you would see them every time. Now you don’t.”

“They’ve been fished for their fins,” she says. “Shark fin soup is a terrible thing. We’re depleting the number of sharks in the ocean at a rapid rate.”

There’s no doubt that the increasing demand for shark fin soup, considered a delicacy in Chinese culture, has contributed to this depletion. Hong Kong is thought to be the largest shark fin importer in the world.

The practice of shark finning, where a shark’s fins are cut off, often while it’s still alive, and the wounded predator is discarded, or thrown back into the ocean, is banned in many countries.

Vanishing sharks

Fishing practices, such as fish aggregating devices, which are floating objects designed and strategically placed to attract pelagic fish, are also thought to have contributed to the decline.

“There’s not that many fish left, especially edible fish,” says Taylor. “There’s not that many sharks left. And while we have harvest breeding aggregations, they’re not going to regenerate.

“We’re stupid. We’re greedy, and we’re pathetic. I won’t be here to see it, but we’re destroying the planet that supports us.”

Despite her frustrations with the state of the marine environment, Taylor, who’s spent over 60 years exploring the ocean, remains a committed and keen diver.

“I would have stopped, probably [if I’d had children], but Ron needed me,” she says. “He needed someone on camera, and I was the subject of his documentaries all through our lives.

“My mother wanted me to have children. But my brothers had the children and I had the adventure.”

Sadly, Ron Taylor died of leukemia in 2012 at the age of 78.

When she looks back on their life together, Taylor says she’s astounded that they managed to make a living while traveling the world, diving to the depths of the ocean and capturing it all on film.

“I’ve had the best life of anybody I know,” she says. “It’s been different to what my parents thought I’d have. But I think I’m one of the luckiest people in the world.

“I was loved by my husband and I was admired by my girlfriends. I think mostly because I had such a beautiful looking husband.

“We were always going somewhere exciting and doing exciting things. So I have no complaints.”

While Taylor has been linked to sharks for many, many years, she stresses that she has an affinity with most underwater creatures.

But she’s always found that people are simply more interested in sharks, even now.

“It’s a bit of a puzzle in a way,” she says. “Because there are other wild animals that are just as interesting and fantastic.

“It seems that the human race likes to have a monster out there, something to be afraid of. Once upon a time, it was witches and devils. Now it seems to be sharks.”

Taylor is keen to follow up “Playing with Sharks” with another project that puts the spotlight on all of her “underwater friends.”

“I’d like to make another documentary about all the guys I’ve known and loved over the years,” she says.

“I’ve had two octopus friends. Three moray eel friends and one manta ray friend,” she says. “All she [the manta ray] ever wanted was to be scratched on the stomach. My husband always filmed, so the footage is there.”

‘Easier to dive than walk’

“Playing With Sharks” is one of two National Geographic specials featuring Taylor to be screened as part of its annual Sharkfest summer event, which brings six weeks of shark related programming.

The second is “Shark Beach with Chris Hemsworth,” which sees her take the Melbourne-born “Thor” actor for a dive off the coast of Australia.

“It probably happened in just three or four days,” she says of her time with Hemsworth.

“We hopped on a dive boat, went out, had a dive. Then went out and watched the whales for a while. Then came in and had a long discussion.”

Taylor, who suffers from arthritis, hasn’t been able to go diving again in a while, but says she’s desperate to get back into her scuba diving gear once travel restrictions, admitting that she feels more mobile underwater than on land.

“It’s easier [for me] to dive than to walk,” she says. “Underwater, there’s no gravity fly. I drop into the water and I can go up or down, left or right with great ease.

“On land, I’m full of arthritis. I’m stumbling around. I can’t spread my wings and fly to the shops underwater. I think I’ll always dive. Even when I’m in a wheelchair. Wheel me in. I’ll be right.”

Although she struggles to dive in cold water now, Taylor is in her element while swimming in the warm waters found in the Indonesian archipelago of Raja Ampat, where she’s planning to head to as soon as it’s safe to do so.

She’s never lost her passion for diving, but admits to being devastated by the changes she’s witnessed in the ocean during her many decades of exploration.

“It’s been a sad change,” she says. “I’m lucky I saw it [the ocean] when it was at its best, when it was pristine.

“I’d drop into the water out of that dinghy to a world that no one else had ever seen or touched. And that’s a wondrous thing to do.

“It was a different world. I’ve lived a long time, and that world will never come back. It’s gone forever.”

But while she longs for the ocean she experienced in those early days, Taylor continues to find joy in the underwater world, and stresses that it’s “still a world of wonder, just depleted.”

“If you go diving, you’ll have a wonderful time [now],” she says. “Because you won’t know what you’re not seeing, what you’re missing.

“I guess it’s like a garden in winter, when the flowers aren’t blooming, but there’s still the odd little daisy poking up.”

“Playing with Sharks” will premiere on Disney+ on July 23.

![<strong>Swimsuit factor:</strong> "We [Ron and I] learned that if I swam around with the sharks in a bikini, it would sell better than if there was no person in the picture," Taylor tells CNN Travel.](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/210715163220-04-valerie-taylor-playing-with-sharks.jpg?q=w_2823,h_1588,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)

![<strong>Dedicated to diving:</strong> "I would have stopped, probably [if I'd had children], but Ron needed me," she says. "He needed someone on camera, and I was the subject of his documentaries all through our lives."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/210715164017-13-valerie-taylor-playing-with-sharks.jpg?q=w_1920,h_1080,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)