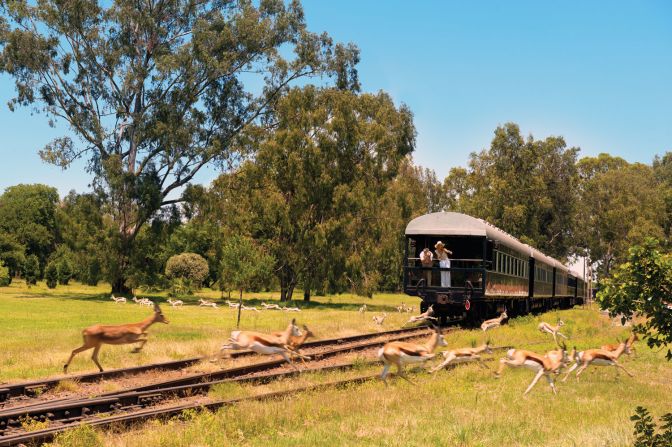

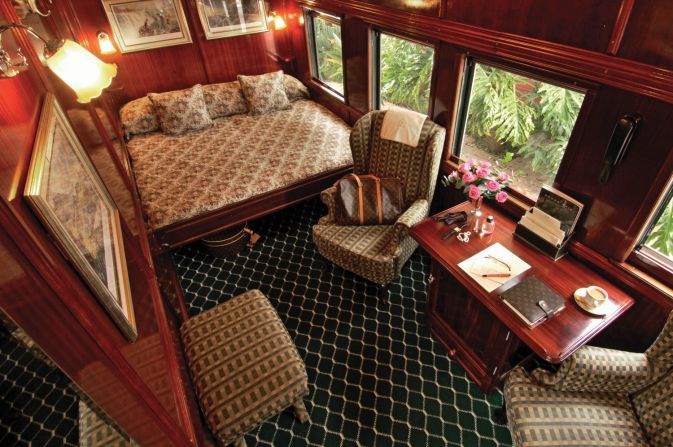

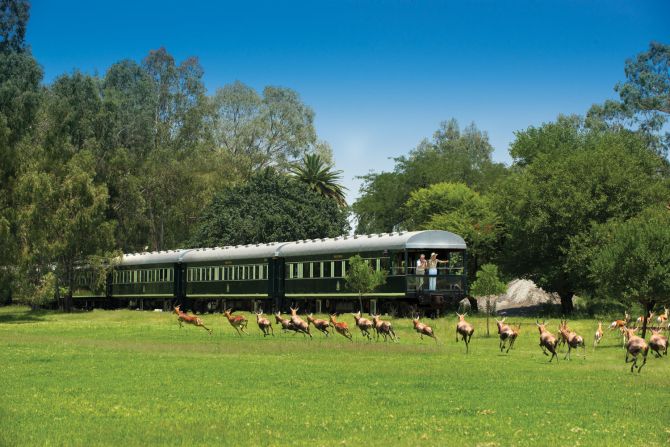

Sometimes, there’s something to be said for slow travel. Sure, a plane ride between South Africa’s Cape Town and Pretoria will take two hours, but it won’t have the same romance as a two-day train journey.

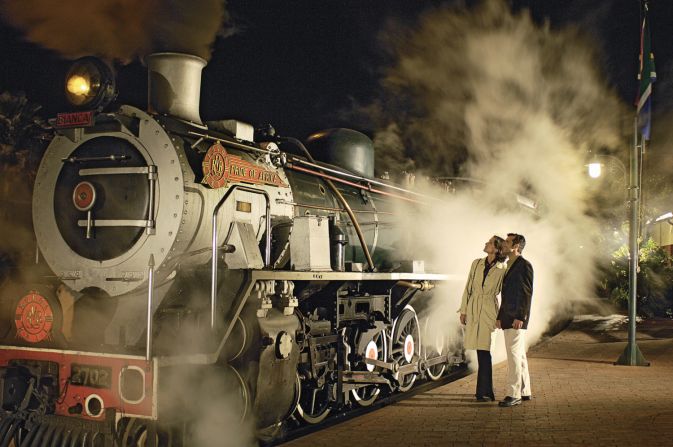

Enter Rovos Rail, a luxury steam train company that offers a series of journeys across South Africa and beyond, and which allows passengers the opportunity encounter the region’s spectacular scenery and some of the big beasts that roam it.

We take a closer look at some of the more extraordinary stops on the 1,000-mile journey.

A Victorian toilet

One of the first stops, 150 miles outside of Cape Town, is Matjiesfontein, a small railway village preserved in the same Victorian style it was built in 125 years ago.

There sits the Lord Milner Hotel, where South Africa’s first flushing toilets, electric lights and telephone dwell. Matjiesfontein is a national heritage site, and one guide John Tienasen is proud of.

“Tourists come from all over the world,” he says. “Here you can see no evil, do no evil, and just listen to the history.”

Bling things

Rovos Rail has more than one route to Pretoria. The train that passes through Durban also hits up Oudtshoorn, a small town with a big reputation.

Known as the “ostrich capital of the world,” Oudtshoorn made a fortune from ostrich feathers, which in the 19th century were all the rage in women’s fashion. Today these giant feathers still have their uses, and local company GM Klein Karoo International sells them to Apple manufacturers in China and luxury car makers to dust off their products.

However the wealth generated by the bird feathers pales in comparison to what lies in Kimberley, on the journey via Johannesburg.

World's most luxurious train journeys

Known as “The Big Hole,” Kimberley’s most famous diamond mine was prodigious in its past, yielding three tons – or 14.5 million karats – of the precious stones.

Further up the road, however, in Johannesburg, is the center of yet another glimmering source of wealth: Gold.

Historian and sociologist Prinisha Badassy argues that by the end of the 19th century, the discovery of gold led to a South African gold rush.

“As word spread around the world, prospectors and gold mining companies came in their droves to South Africa, specifically Johannesburg.”

The growth of the city and its economic boom was not without its pitfalls, however.

“Gold mining created a group of South Africans called the Rand Lords,” she explains. “Below that you’d have white collar workers, and really below that your blue collar workers… And so you start to see the segregation, the racial segregation, of different classes of people in the city.”

When the gold dried up, Johannesburg’s economy was forced to diversify, but the barren mounds of earth extracted from the mines remain, testament to its industrial past.

From the country’s largest city, the train passes on to Pretoria and journey’s end, where Rovos Rail has its own private station – a location that doubles as a workshop to renovate old carriages. It’s a fitting symbol for the journey from Cape Town: a link both between present and past; nurtured and flourishing in the 21st century.