Editor’s Note: CNN Travel’s series often carries sponsorship originating from the countries and regions we profile. However, CNN retains full editorial control over all of its reports. Read the policy.

Story highlights

Singapore's street food stalls are disappearing due to high costs and lack of succession

A new crop of "hawkerpreneurs" is striving to preserve the city-state's culinary legacy

Other chefs are exploring creative neo-Singaporean cuisine

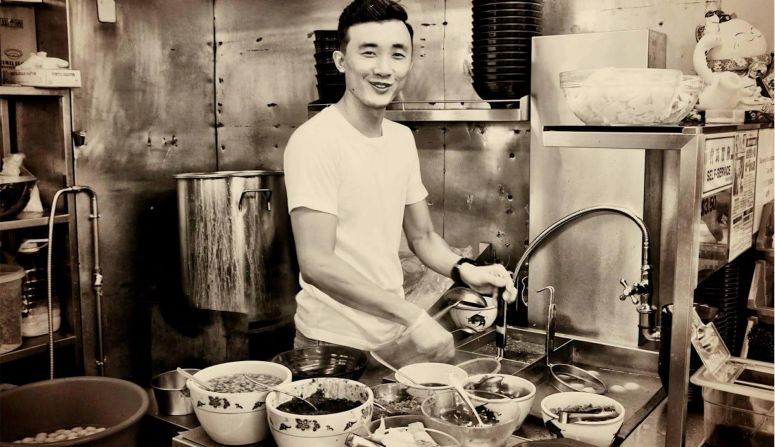

Douglas Ng, 24, is a rare fresh-faced “hawkerpreneur” at Golden Mile Food Centre, a hawker center in Singapore.

The owner/chef of Fishball Story, Ng arrives to work during the dark hours of the morning to prep for the day.

He kneads fishball dough, prepares sambal-spiked chili paste and fries condiments like lard and shallots. Ng’s fishballs are unique and legitimately old school. They’re prepped exclusively with yellowtail fish and seasonings, without the addition of flour, the way most fishballs are made nowadays.

After one-and-a-half years working this space with many 12-hour days, Ng takes home just about S$1,000 ($712) each month. When he recently increased fishball prices from S$3 to S$3.50, he was met with a 40% plunge in business.

Editor’s note: Since being interviewed for this story, Ng has temporarily closed his stall. He tells CNN he plans to reopen his business soon in a new location.

Singapore’s hawker foods: Vanishing tradition?

Singapore’s aging hawker trade is increasingly facing a dire future. Stalls are stymied by a host of issues that are endangering this once-prized commodity.

“Our hawker heritage differentiates us from other countries,” says Willin Low, the chef-owner of Wild Rocket, Wild Oats and Relish local restaurants, and the man widely regarded as the godfather of modern Singaporean cuisine. “It unites Singaporeans from different ethnic backgrounds, but it looks like the heritage is thinning.”

One reason is lack of ownership succession.

“The hawker trade is not something that the young generation fancies,” says Ng. “It’s a tough and unglamorous job. It does not pay well and there isn’t much work-life balance. Rentals are high, labor is hard to find and the cost of ingredients is increasing.”

A growing local resistance to paying what hawkers say is a fair price for street food doesn’t help.

“We’d better eat soon kueh now before it’s too late,” says Low, referring to the local handcrafted dumplings traditionally made with turnip and bamboo shoots. Making the beloved street snack, he says, is becoming a lost art.

10 Singapore street foods guaranteed to make you hungry

New crop of ‘hawkerpreneurs’

There is hope on the streets. Even as hawker culture faces difficulty, a new band of innovative “hawkerpreneurs” has emerged.

If they’re rare, their motives at least seem pure.

“Many people wonder why a young man like me came into this industry,” says Ng. “I am here to preserve the hawker heritage, to find a way to make money and, most importantly, be happy. I believe my perseverance will pay off one day and I will be successful and prove to young people that they can do it too.”

Nick Soon started One Kueh At A Time eight months ago, selling teochew kueh (a glutinous rice-based snack with sweet or savory fillings) at Jalan Berseh Food Centre.

His stall sells four types of artisan kueh – all for S$1 apiece – including steamed-to-order ku chye kueh (chive kueh) and soon kueh (with turnip but not traditional bamboo shoots).

The 40-something former insurance executive, who makes all of his food entirely by hand, sees his mission as part of a family legacy.

Soon’s mother had been taking orders and making kueh from home since 1983. Now that she’s in her 80s and retired, Soon wants to continue her tradition.

Filial duty

At Jin Ji Braised Duck and Kway Chap stall in Smith Street Food Centre, 37-year-old Melvin Chew is helming the hawker stall that his parents founded when he was just five.

After his father passed away last year, Chew left his job as a garage technician to run the business full time. He says he wakes up at 5 a.m. to reach his stall by 7 a.m. and doesn’t leave until about 8 p.m.

Apart from selling traditional teochew-style kway chap (flat rice noodles in meat broth served with a selection of pig offal, braised duck and condiments), Chew has introduced a bento set to reach out to a younger generation of eaters.

The set bundles the stall’s traditional offerings with newly introduced soft-centered eggs and a choice of yam rice bowl or kway chap.

“We’ve more than a 30-year history selling kway chap,” says Chew. “Even though being a hawker is hard work – just think of all the pig intestines and stomachs I have to wash daily – and involves long hours, I want my parents’ legacy to live on.”

11 best new restaurants in Singapore

Creativity meets tradition

The move to preserve Singapore street food has also moved into more traditional restaurants, whose chefs have giddily given the city’s classic plates an update.

At the decade-old Wild Rocket, Low serves contemporary Singapore cuisine adapted from the city’s favorite cheap eats.

Laksa, a popular Peranakan noodle dish with spicy broth flavored with coconut milk, is reinvented as a pesto sauce and paired with pasta.

On Low’s newly introduced “omakase” menu, bak chor mee (minced pork noodles) steals the spotlight. Low’s version is made with glass noodles cooked in Iberico pork fat topped with torched mixed tuna and scallions.

At 3-year-old Candlenut, Malcolm Lee recreates Singapore’s ubiquitous ayam buah keluak (chicken with Indonesian black nut) as a rich paste blanketed on sous-vide wagyu beef short ribs.

Lee introduced an “ahmakase” menu – the name is a play on “ah ma” (grandma) and omakase (a Japanese meal with dishes selected by the chef) – with creations like a thick broth of buak keluak with beef cheek, shallots and aromatics.

At Restaurant Labyrinth, chef-owner Han Liguang does a new take on chili crab.

The former banker has remade Singapore’s de facto national street dish with deep-fried soft shell crab flanked by a dollop of piquant chili crab ice cream with man tou (Chinese steamed bun).

It’s another effort to save, or at least evolve, the country’s legacy dishes.

“Neo-Singapore cuisine is an expression of myself growing up in the modern age whilst being exposed to traditional flavors, some of which are being lost through time,” says Han. “Singapore celebrated its 50th birthday this year (2015), I want my cuisine to celebrate modern Singapore while also remembering our roots.”

Candlenut, 331 New Bridge Road, 01-03 Dorsett Residences, Singapore

Jin Ji Braised Duck and Kway Chap, Blk 335, Smith Street 02-156, Singapore

One Kueh At A Time, 02-61 Berseh Food Centre, 166 Jalan Besar, Singapore

Restaurant Labyrinth, 8 Raffles Ave., 02-23 Esplanade Mall, Singapore

Wild Rocket, 10A Upper Wilkie Road, Singapore, Singapore

This story was originally published in December 2015.

Evelyn Chen is a food and travel writer and the regional academy chair for World’s 50 Best Restaurants and Asia’s 50 Best. In between dinners and writing assignments, the former Zagat editor blogs about food at bibikgourmand.