From chilli crabs to chicken rice, char kway teow to laksa, Singapore’s open-air hawker markets are a must-visit destination for those in search of the rich yet cheap offerings the Little Red Dot is known for.

But travelers exploring the city’s buzzy local food scene may have missed out on one special dish: rojak – aka the Singapore salad.

Singaporeans have an intense, almost obsessive, adoration for this regional creation, which is nothing like the leafy green salads known to the Western world.

Meaning “mixed” in Malay, rojak is a traditional salad of fruits and vegetables commonly found in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. In Singapore, its storied past harks back to the glory days when rojak was hawked from pushcarts and bicycles on city streets.

Across the Malay Archipelago, this humble salad dish commonly features pineapples, jicama (Chinese turnip), prawn paste and tamarind but, over time, serving styles have invariably been adapted to reflect the cultural influences of each locale.

In Singapore, rojak is a mishmash of fresh tropical fruits like pineapples (sometimes star fruit) as well as raw and blanched vegetables like water spinach, bean sprouts, cucumber and jicama. It’s mixed on the spot in a gigantic bowl, topped with youtiao (deep-fried dough fritters), toasted beancurd, a sprinkle of ground peanuts and a dash of torch ginger flower.

For many, however, the highlight is its punchy dressing – a cocktail of prawn paste, sugar, tamarind, lime juice and chilli paste. Headlining the dish, it delivers a melange of pungent, sweet, sour and tangy flavors with every bite.

At Lau Hong Ser Rojak, a 46-year-old rojak stall located on the upper floor of Singapore’s Dunman Food Centre, second generation owner Lim Khai Ngee still cooks the dough fritters, fried beancurd puffs and dried cuttlefish that grace his rojak offerings over a charcoal grill – a rare sight.

But Lim’s rojak sauce too deserves high praise – an unusually thick, gooey and sticky prawn paste ambrosia that coats the pineapples, jicama, cucumber and medley of other ingredients with a heady umami, making this age-old stall a necessary pit stop for rojak lovers.

Not to be mistaken for Indian rojak, which shares the same name but is an entirely different beast of mostly deep-fried snacks — think dough fritters, battered prawns, beancurd and potatoes — served with a sweet potato-thickened chilli dip, rojak is typically sold by Chinese vendors like Lim while Indian rojak is hawked by the Indian Muslim community.

The origins of rojak

Despite its wide-spread consumption, rojak’s exact origins are murky. But to Damian D’Silva, chef of Restaurant Kin and an authority on Singapore heritage food, its link to Indonesia is clear as day.

“Rujak (Indonesian) or rojak (Singapore/Malaysia) has its roots in Indonesia,” says D’Silva. “In fact, rujak has been around in different provinces in Indonesia for hundreds of years.”

The Singapore variant of rojak, he adds, is an eclectic mix of Malay, Chinese and Peranakan influences, with prawns and dough fritters representing the Chinese influence; torch ginger, chillies and tamarind being the Malay/Peranakan influence.

“In the past, this dish was sold by pushcart hawkers and they were served on opeh leaves, folded and secured with a toothpick,” says D’Silva, who had his first taste of rojak at a pushcart on Hill Street in the 1960s.

He adds that the ingredients were always a little different, depending on the fruit season. Occasionally, there were green mangoes, rose apple, buah kedongdong and kwini (fragrant mango) but cucumber, jicama, pineapples, kangkong and dough fritters have always been fixtures.

In Indonesia, where rujak has been served as part of a traditional Javanese prenatal ceremony called Naloni Mitoni (meaning seventh month), multiple variations of rujak are rife, with some variants indigenous to certain regions.

“Aceh serves a unique rujak called the rujak Blang Bintang (a district in Aceh),” says William Wongso, a culinary expert from Indonesia. “Apart from the usual fruits that you’ll find in rojak buah, the salad also features unusual ingredients like sago palm and shell of the kawista fruit.”

According to Wongso, the most common type of rujak in Indonesia is rujak buah (fruit rujak), in which unripe fruits like mango, pineapple, papaya or rose apple are tossed in a sweet and spicy dressing of palm sugar, tamarind, chillies and shrimp paste.

Local comedian and host Hossan Leong claimed in 2015 that rojak “best represents the history of Singapore food culture” because “it’s a very nice melange of the different sort of tastes we have.”

Elevating the Singapore salad

Due to its popularity with locals, this dish has increasingly found a new home in less humble surrounds, giving chefs – and their menus – a greater sense of place.

Three Michelin-starred Odette, which has been ranked number one on the Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants list two years in a row, introduced “Promenade a Singapour” on its modern French tasting menu in April 2019.

An ode to his adopted city’s well-loved salad dish, chef Julien Royer’s “rojak” is an assembly of five baby greens and about 10 different flowers, including blue pea flower and torch garlic flower, all farmed in Singapore, tossed with almost 10 other ingredients including jicama, peanuts and pickled ginger flowers and finished with a dressing of shio kombu powder sprinkled over a drizzle of extra virgin olive oil.

Even in the absence of piquant shrimp paste, the restaurant pulls off a refined take that most local diners will undoubtedly identify as uniquely Singapore.

Over at one Michelin-starred Labyrinth, chef Han Li Guang’s “Homage to My Singapore” tasting menu also features a rojak dish that puts the spotlight on about 10 different types of local flora. Amongst them are cat whiskers, Okinawa spinach and Indian borage.

They are flanked by a scoop of cempedak and jackfruit ice cream and a sprinkle of peanuts. His dressing hews closely to the classical taste with a simple concoction of shrimp paste and an acidic-tasting stingless bee’s honey from Batam, Indonesia.

While it’s held on to its monopoly status as arguably the only local salad known to Singaporeans, rojak has in recent years been joined in restaurants by kerabu.

Described by The Star newspapers as a “riotous, tropical local salad made using vegetables and herbs, and dressed with a fiery sambal, coconut and lime,” kerabu is a forgotten dish that emerged over time in Malay cuisine “as a way to utilize both raw and cooked leftover ingredients.”

But to D’Silva, who has a Nyonya maternal grandmother and Eurasian paternal grandfather, kerabu is “heritage salsa”.

“The most common kerabu are the ones that we still see at some Nasi Padang stalls,” he says. “It’s a dish of bean sprouts, winged beans, daun pegaga, onions and toasted coconut flavored with lime juice and salt.”

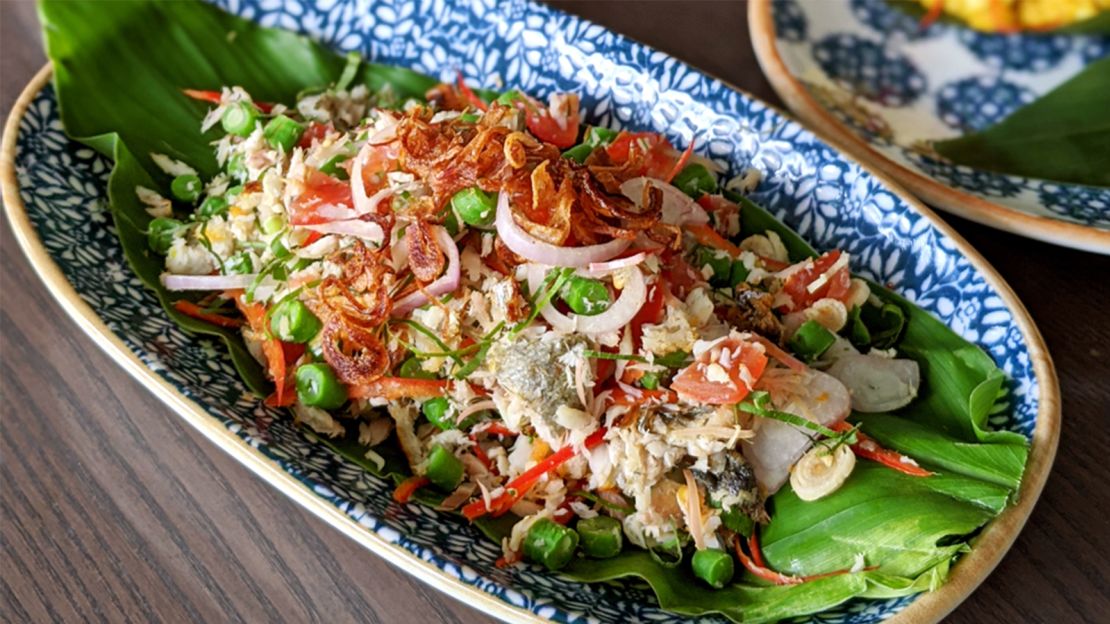

At Restaurant Kin, where he commands the kitchen, he has recently introduced Kerabu Ikan Goreng. Served as an appetizer, wild-caught Spanish mackerel is matched with fresh tomatoes, quick blanched long bean, shallots, chilli, turmeric leaf as well as ginger flower, and dressed with calamansi.

“There are many different types of kerabu,” says D’Silva, “But we don’t hear about them because many of the ingredients that go into these salads – like the papaya flowers – have disappeared.”

But the self-taught chef is hopeful that in time, and only with the help of local farmers, some of these “forgotten” flora will thrive once again.

With that, he is optimistic of giving more varieties of kerabu its much-needed place on his heritage menu.