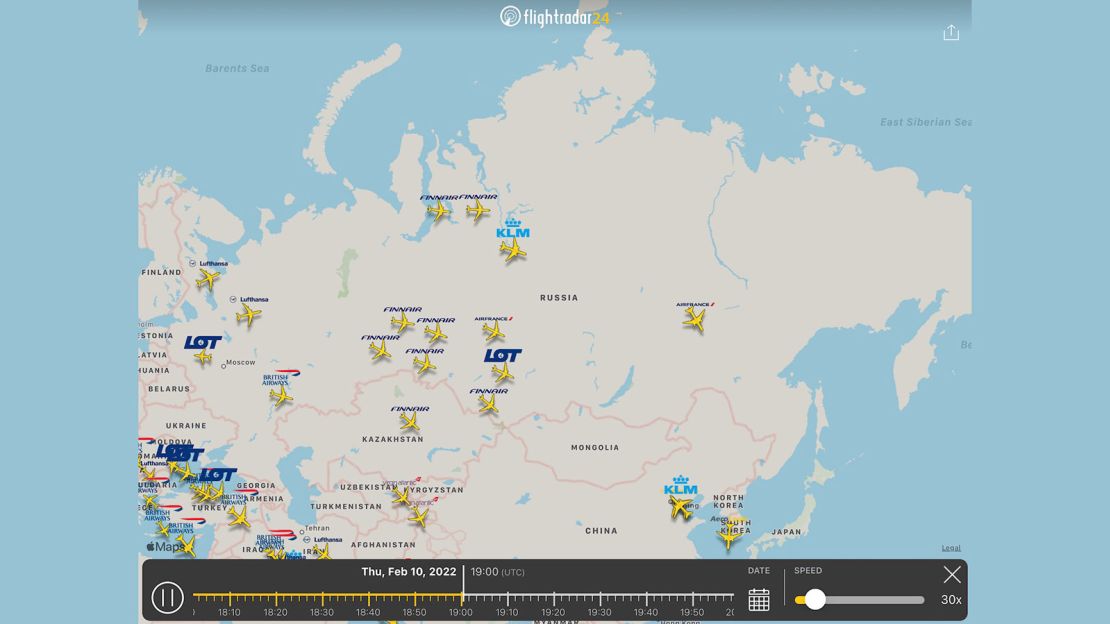

The closure of Russian airspace to some international carriers, including many in Europe, has forced airlines to seek alternate routes. For some flights, such as those linking Europe and Southeast Asia, that’s especially problematic since Russia, the world’s largest country, stands directly in between.

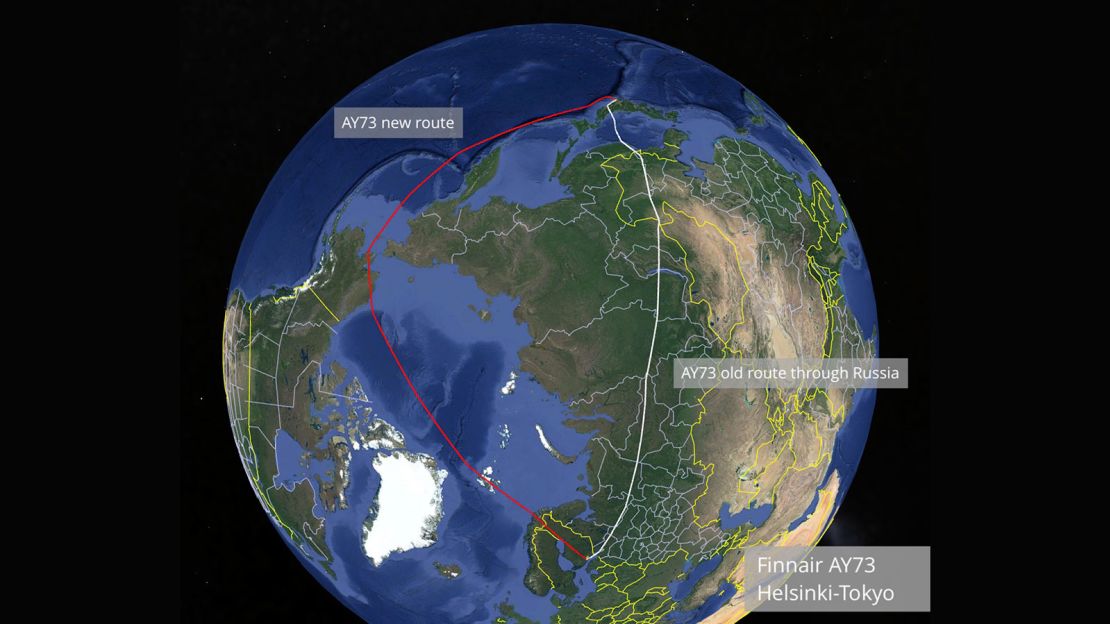

The problem is best illustrated by Finnair’s flight from Helsinki to Tokyo. Before the invasion of Ukraine, planes from Finland’s national carrier would take off and quickly veer into the airspace of neighboring Russia, crossing it for over 3,000 miles.

They would then enter China near its northern border with Mongolia, fly in its airspace for about 1,000 miles, before entering Russia again just north of Vladivostok.

Finally, they’d cross the Sea of Japan and turn south towards Narita Airport. The journey would take just under nine hours on average and cover nearly 5,000 miles.

The last such flight departed on February 26. The next day, Russia barred Finland from using its airspace, forcing the temporary cancellation of most of Finnair’s Asian destinations, including South Korea, Singapore and Thailand.

By that point, however, the airline’s route planners had long been at work to find a solution. “We made the first very rough calculation about two weeks before the actual closure of the airspace,” says Riku Kohvakka, manager of flight planning at Finnair.

The solution was to fly over the North Pole. Instead of heading southeast into Russia, planes would now depart Helsinki and go straight north, heading for the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, before crossing over the pole and Alaska.

Then they would veer towards Japan flying over the Pacific, carefully skirting Russian airspace. That’s not as straightforward as before: The journey now takes over 13 hours, covers approximately 8,000 miles, and uses 40% more fuel.

Safety first

Finnair started flying via the polar route to Japan on March 9. So, how does an airline completely redesign one of its longest flights in just over a week?

“All major airlines have their own computerized flight planning system, which they use to plan routes and change them,” explains Kohvakka. In the software, the airspace of specific countries can be crossed out and waypoints can be manually inserted to help it calculate alternative routes.

The next step is a new operational flight plan, which tells the crew what the planned route is, how much fuel they need, how much the plane can weigh and so on.

“From experience, we knew we had two possibilities: one via the north, and one via the south,” says Kohvakka.

In addition to the polar route, Finnair can also reach Japan by flying south of Russia – over the Baltics, Poland, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan to China, Korea and then to Japan. It’s longer, but if wind conditions are particularly favorable it can be used, resulting in a similar flight time.

Then, fuel consumption data, together with navigational fees, is used to estimate the cost for the flight.

“After that, we need to check what kind of terrain we are flying over. For example, to see if the elevation at any point of the route requires special planning, in case we lose an engine or pressurization – something that is always considered when preparing a flight,” Kohvakka says.

Once the new route is approved, the focus shifts to aircraft equipment and the associated processes and regulations.

Among them is one called ETOPS (“Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards”), which dates back to the 1950s, when aircraft engines were less dependable and more prone to failing. ETOPS is a certification provided to aircraft that determined how far a plane with only two engines could fly from the nearest airport, in case it needed an emergency landing due to engine failure. “We need to have a suitable airport where we can divert to within a certain time limit,” says Kohvakka.

The regulation was initially set to 60 minutes, but as airplanes grew more dependable, it was gradually extended. Just a few weeks ago, Finnair was operating under the widely adopted ETOPS 180 rule, which meant that its twin-engine aircraft could fly up to three hours away from the nearest airport at any time.

The new Arctic route, however, flies over very remote areas, where airports are few and far between. As a result, the airline had to apply for an extension of that protocol to 300 minutes, meaning the Airbus A350-900s it uses to fly to Japan can now stray as far as five hours away from the nearest airport, while still meeting all international regulations and safety protocols.

Cold War route

Airlines routinely deal with closure of airspace, for example during spacecraft launches and military drills, and prior conflicts have curtailed or halted flight over Afghanistan, Syria, and Pakistan. A closure of this magnitude, however, has not occurred since Cold War times.

Because overflight rights are negotiated between nations rather than individual airlines, Russia and Finland secured an agreement only in 1994, two years after the Soviet Union disintegrated.

Previously, Finnair, like most other European airlines, did not fly over the Soviet Union at all. When it began operations to Tokyo in 1983, it also flew across the North Pole and Alaska.

“So this route is not totally new to us,” says Kohvakka. Finnair was the first airline to fly the route nonstop, using DC-10 aircraft, whereas most others at the time had a refueling stop in Anchorage.

The new route increases fuel consumption by a whopping 20 tons, making the flights environmentally and financially challenging. For that reason Finnair is prioritizing cargo, where demand is stronger, and limiting passenger capacity to just 50 seats (the Airbus A350-900s used on the flights could carry up to 330 people).

“The extra trip length will make fewer flights economically viable,” says Jonas Murby, an aviation analyst at Aerodynamic Advisory. “They become very dependent on a high mix of premium passengers and high-yield cargo; this in an environment where overall demand for travel along these routes is still relatively low. I doubt this will be a widely adopted strategy.”

Japan Airlines is so far the only other airline using the polar route for its flights between Europe and Japan. The London to Tokyo service now flies over Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Iceland, which has increased the average flight time from just over 12 hours to about 14 hours and 30 minutes, according to Flightradar24.

Northern lights

An extra four hours of flight time also has an impact on passengers and crew, further increasing costs.

“Usually we fly to Japan with a crew of three pilots,” explains Aleksi Kuosmanen, deputy fleet chief pilot at Finnair, who is also a captain on the new flights. “Now we operate it with four pilots. We have a specific flight crew bunk where we can sleep and have a rest, and we have also increased the number of meals.”

Passengers have reacted cheerfully to the new route, according to Kuosmanen.

“I would say that people were enthusiastic,” he said. “Many were asking at what time we would be going across the pole and if northern lights were expected.”

There’s also an advantage to having a 300-seater capped at just 50 passengers: “I had a stroll through the cabin during the night and… let’s say, they had space.”

Finnair is also giving out stickers and “diplomas” that certify to passengers that they have flown over the North Pole.

Technically, the polar route doesn’t pose any extra safety risks.

“Cold weather is probably the first thing that comes to mind, and it’s true that there are regions with cold air masses at high altitude, but we’re fairly used to this when we fly northern routes to Tokyo in the Russian airspace anyway,” says Kuosmanen.

One issue could be that the fuel temperature becomes too low, but the A350 is particularly resilient against cold air, Kuosmanen says, which makes it ideal for the route.

There are other minor quibbles. For example, satellite voice communications don’t cover the whole Arctic region, so crews have to rely on HF radio, a technology that is almost 100 years old.

In addition to that, there are areas with strong magnetic radiation to be considered during the flight.

“We have a good old magnetic compass in the aircraft, in addition to several modern navigational aids, and it went a little bit haywire while we were flying over the magnetic North Pole,” says Kuosmanen. (This causes no harm to the aircraft at all).

Overall, from a pilot standpoint, the polar route makes things more interesting, but doesn’t fundamentally alter the job.

“The polar area is probably where every pilot who flies long-haul wants to operate,” says Kuosmanen. “But once one is well prepared and well briefed, it’s just another day at the office.”

Top image: Finnair is routing flights to Asia over the North Pole. Credit: Finnair