Editor’s Note: Every week, Inside Africa takes its viewers on a journey across Africa, exploring the true diversity and depth of different cultures, countries and regions.

Story highlights

Until a decade ago, running water and electricity were nearly unheard of around the Atlas Mountains

Tourists are drawn by the remoteness of the mountain villages

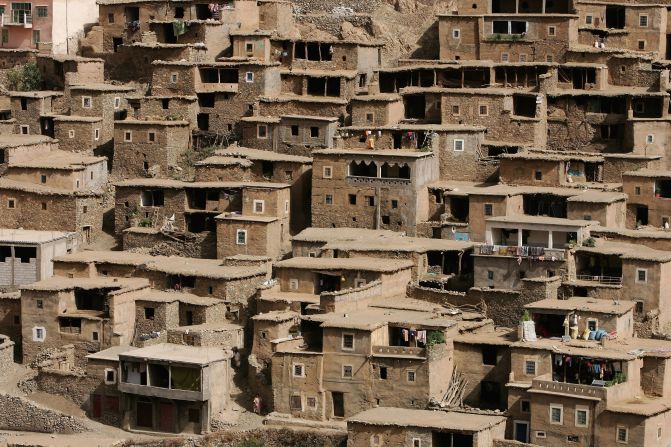

The Atlas Mountains have long been home to some of North Africa’s most remote villages.

Until a decade ago, running water and electricity were nearly unheard of, and even today are considered luxuries in most of the mountain towns.

The local Berber that populate the villages measure distances by hours and days – the amount of time it usually takes to travel between destinations. Because there aren’t any local shops, villagers rely on traveling markets to obtain goods. Many of the vendors still rely on ancient techniques.

“Our grandmothers were making carpets before us. The best carpets in the world can be found in Morocco. It’s an art,” says Fatima Imerhan, a local carpet weaver.

Morocco guide: 10 things to know before you go

Bring in the tourists

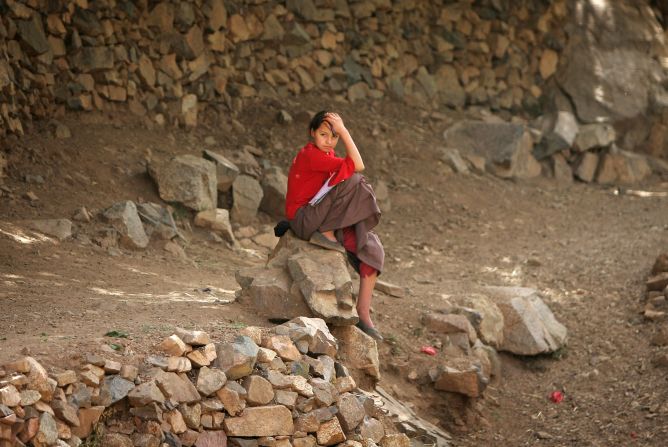

Many locals cite the tranquility that life in the Atlas Mountains has to offer as an asset.

“It’s better than a city because in cities there’s a lot of noise, cars, and pollution. But here it’s nice because it’s quiet, (and there’s) fresh air,” says resident Rachid Souktan.

This is a sentiment that is increasingly reflected worldwide, as tourists have started to arrive in increasing numbers in recent years.

The majority trek out to Imlil, which has become a kicking off point for skiers and mountain climbers alike. Kasbah Du Toubkal, the village’s first hotel, opened its doors in 1995. Kasbah started its life as a colonial mansion, but later fell into ruin.

“There was nothing at the Kasbah before. It was completely abandoned and mostly destroyed,” says Omar Ait Bahmed, the hotel’s manager and part-owner. Since, it has attracted some high-profile travelers, including Martin Scorsese, who shot parts of his film “Kundum” in the hotel in 1997.

10 street foods to try in Morocco

Falling apart

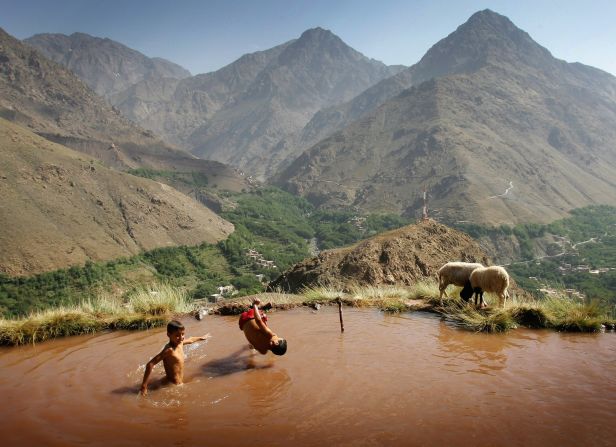

Unfortunately, tourism doesn’t just bring revenue to the region, it also brings problems.

Since becoming a travel hotspot the local river has become more polluted and trekkers have complained of garbage strewn along the path to the Mount Toubkal.

The hotel is doing its bit to protect the local environment, using solar panels and charging guests a 5% tax that goes into local cleanup efforts. Ait Bahmed’s partner, Mike McHugo, worries it may not be enough.

“(The villagers) have to be very aware that development doesn’t destroy their rich culture. And that’s one of the reasons tourists come here. So they also have to understand that they mustn’t spoil the environment, both physical environment and cultural environment, otherwise you’ll spoil the goose that lays the golden egg,” he says.