Kim Kyung-seop recalls going to cheap bars after class with his friends, where they binged on as much makgeolli as possible.

“You know the saying, ‘alcohol consumes men?’ It was like that.”

Makgeolli, the milky and often sweet traditional rice wine from Korea, was chosen for its price, not flavor.

In 1989, when Kim entered college, half a gallon of makgeolli cost about 40 cents. He and his friends would sit around a table, pouring makgeolli from a brass kettle into individual brass bowls, as is tradition.

Kim, now an adjunct professor at Global Cyber University in Seoul, has been teaching makgeolli brewing techniques for 10 years. Yet he remembers his early encounter with the drink being unpleasantly sour and bitter.

“When we were with women, we would drink beer. But among the boys, we drank makgeolli.” Makgeolli – with its less chic reputation – was unfit for impressing women.

Two decades later, in bars across South Korea’s capital, the lackluster drink from Kim’s memory was becoming trendy, this time in the hands of a young generation of entrepreneurs and brewers.

“We worked very hard to get rid of the established images people hold of makgeolli,” says Kim.

Kim Min-kyu (no relation to Kim Kyung-seop) is one brewer who had been leading the change. He launched his premium makgeolli brewery Boksoondoga in 2009.

Min-kyu’s teetotaler, devout Christian father opposed his plan – especially after having spent the family fortune supporting his son’s five years of training as an architect in New York City’s Cooper Union. His father even smashed a clay pot used for brewing makgeolli in a fit of anger.

Min-kyu was not deterred. He believed in the strength of his grandmother’s makgeolli recipe.

When he was a child, he would visit her farmhouse in Yangsan, a town in the southeast. She would mix half-steamed rice with her homemade yeast and water. And he would listen to the quiet bubbling of air as the mixture fermented into makgeolli. His fondest memories were his grandmother generously sharing the finished brew with the neighbors, after which they would sing and dance.

He convinced his family that brewing is an extension of architecture for him. Applying his training, he designed the branding, the marketing materials and the brewery building, while his mother brewed the makgeolli, creating the first bottle of Boksoondoga. Doga means “brewery,” and Boksoon is Kim’s mother’s name.

The timing was fortuitous. Makgeolli was coming out of a century-long dark age.

The history of a drink

Makgeolli is a combination of the Korean words mak (meaning “roughly done” or “a moment ago”) and geolleun (“filtered”).

While the name first appears in “Gwangjaemulbo,” an encyclopedia presumed to have been written in the 19th century, the opaque alcoholic drink likely dates back a millennium.

One early 20th century record claims that it was consumed in every corner of Korea.

“Makgeolli is inherent to Korean culture, it’s the drink of Korean people,” Kim Kyung-seop says.

One reason for the popularity is its simplicity. It is a mixture of steamed rice, yeast and water, left to ferment for a few weeks in a clay pot. Many families across Korea brewed their own drinks with their unique recipe.

The Japanese colonization during the first half of the 20th century brought the end of many cottage industries. The colonial government phased out homebrewers in favor of standardized, industrial liquor makers. All alcohol-making was taxed and licenses were required, even for self-consumption.

A few mass-produced drinks dominated the market and, by 1934, homebrewing was outlawed.

World War II and the Korean War left the country devastated. The new government continued the policy of tightly controlling alcohol production. As the food shortage worsened in the 1960s, using rice — makgeolli’s key ingredient — to produce alcoholic drinks was banned.

Manufacturers used wheat and barley as substitutes and makgeolli’s popularity sunk. It was supplanted by modern soju, a clear liquor made by diluting ethanol. As the economy improved and rice supply outstripped consumption, the rice alcohol ban was lifted in 1989 and homebrewing was made legal again in 1995. But much tradition was lost.

Bringing it back home

The recovery of the lost art of makgeolli brewing can largely be credited to pioneer researchers like Park Rock-dam. Park traveled across Korea for 30 years collecting recipes and recreating old techniques.

The government also reversed course on its previous policy, embracing traditional alcohol as a proud heritage – and potentially lucrative – industry.

In 2016, the government allowed small scale breweries and distilleries to sell their alcoholic drinks by lowering the brewing tank size requirement from 5,000 to 1,000 liters. The next year, traditional alcoholic beverages were given the unique privilege of being sold online and delivered directly to consumers.

While the Covid-19 pandemic prevented people from going out to bars and restaurants, online and offline sales of makgeolli soared. According to a 2021 report published by Korea Agro-fisheries and Food Trade Corporation (aT), a government-operated company that promotes agricultural products, the makgeolli market grew by 52.1% while the total liquor market shrank by 1.6% in 2020.

In Kim Kyung-seop’s makgeolli class, half of the students are entrepreneurs, many of them women in their 30s or younger. Ten years ago, almost everyone in class was over 50 and looking to brew makgeolli as a hobby in their retirement.

Since 2009, the number of makgeolli brewing license holders have increased by 43%, according to National Tax Service data.

Kim says that opening a makgeolli brewery is much easier than any other type of alcohol. While equipment for setting up a beer microbrewery is around 200-300 million won ($155,000-233,000), equipment for a makgeolli brewery can be acquired for 10 million won ($7,800), Kim says. Furthermore, it only takes four 3-hour classes to brew something that’s better than the mass market makgeolli, he adds.

Going global

An Australian citizen, Julia Mellor originally came to South Korea to teach English. Then in 2009, she encountered makgeolli.

Now, her business The Sool Company provides makgeolli classes and consultations for those interested in opening their own brewery, but most of her clients are from overseas. She says her business quadruped during the pandemic.

Her clients are from countries like the US, Singapore and Denmark. Many of them are members of the Korean diaspora. “They watch Korean people enjoying it here and they are inspired to bring it back to their country,” she says.

“It was so different, so interesting. It is rare to discover something people in the world haven’t heard of.”

She organized meetups with fellow enthusiasts and eventually taught herself Korean because most resources were not available in English.

Mellor believes makgeolli will appeal to foreign audiences.

“It’s very easy to homebrew. You simply need rice and nuruk (yeast).”

And for her, propagating the makgeolli carries another layer.

“This is saving something that was on the brink of disappearing,” says Mellor.

Kim Min-kyu says his makgeolli will be sold in the US and Austria this year and other Western buyers have been approaching him. His makgeolli is already a hit in Japan, where it became popular during Hallyu, or the Korea-wave in the mid-2000s, a period when the success of K-dramas and K-pop opened the door to other cultural exports like kimchi and traditional drinks.

“To foreign consumers, this natural fermentation is considered healthy, organic and clean. And it’s a type of alcohol they have never seen before,” Min-kyu says.

Korean “soft power” has expanded beyond Asia in the past few years. He believes makgeolli can ride this wave.

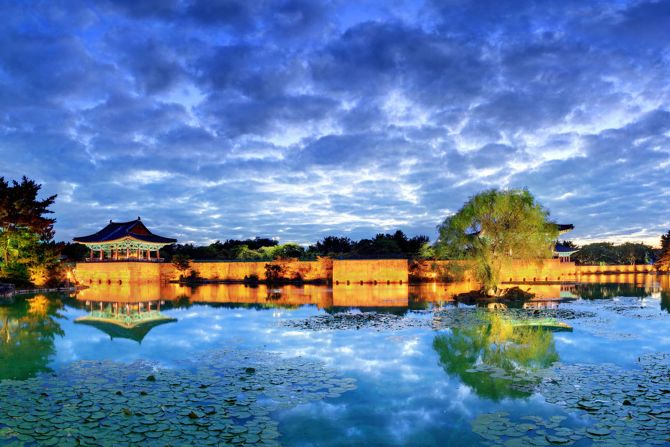

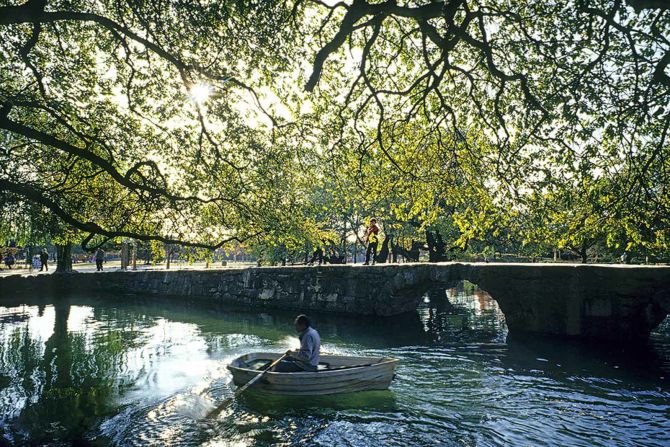

3 photographers share their favorite South Korea travel spots

Making it cool

Despite the rapid advance of makgeolli, the South Korean alcoholic beverage market is still dominated by soju and beer, which account for more than 80% of sales.

Min-kyu says the greatest challenge facing makgeolli makers is the public perception that the drink is for old people. Most of his advertising and marketing focuses on changing this perception. In one ad, a sharp-looking male model with shaved head and eyebrow piercings delicately pours the makgeolli into a champagne flute.

Changing perceptions relating to the foods best paired with makgeolli is another obstacle.

In Korean culture, alcohol is almost always consumed with a set meal or snack. For makgeolli, this is jeon, a Korean savory pancake made by frying meat or vegetables in seasoned flour batter.

“A cool sip of makgeolli after a bite of savory scallion jeon acts as a palate cleanser readying you to fully enjoy another savory bite,” Kim Kyung-seop says.

The combo is especially popular on rainy days. The sale of makgeolli and ingredients for jeon climbs sharply on rainy days across major convenience store chains, according to a report by the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

But premium makgeolli, with its wide spectrum of flavor, effervescence and body can pair well with any type of food, Min-kyu says.

“I drink it with jajangmyeon (a Chinese-Korean noodle dish) and it pairs very well with ice cream too. Because it’s a fermented drink, it tastes great with other fermented food. I think it’s delicious with kimchi and really flavorful cheese,” Min-kyu added.

Boksoondoga makgeolli was recently the main offering at a gastropub inconspicuously nestled in the trendy Hapjeong district of Seoul. Stylish bartenders deftly poured the drink into stemless wine glasses. The customers, mostly young professionals, savored the drinks while relaxing to hip-hop music. In a leather-bound menu, beef tartare was being offered alongside an array of other premium makgeolli brands.

At the tables, more women filled the seats than men did. After each pour, the bartender explained the flavors and the origin. They smiled. They lifted the glass to their lips, carefully listening to each note hidden in the drink.

Jihye Yoon and Minji Song contributed to this report