Cottar’s 1920s Camp is popular with guests yearning to recreate “Out of Africa” – but without the malaria, lion attacks and airplane crashes.

It’s the oldest and most prestigious lodge in Kenya’s Masai Mara wildlife reserve, a luxury 100-year-old establishment with Edwardian-style tented bedrooms, a mahogany bar overlooking the open bush and outdoor canvas baths that make you feel like Robert Redford could start washing your hair at any minute.

A hundred years after its launch, the camp is still beloved by film stars, royalty and heads of state – one of the owner Calvin Cottar’s many after-dinner stories involves an actual queen running back to the jeep after being interrupted mid-pee by an irate lioness.

And yet, with the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, younger Kenyans have started questioning whether White-run lodges should even be using Britain’s long and often devastating period of colonial rule as a way to sell vacations – a subject that has gained traction on Twitter and was tackled by a recent exhibition at the Nairobi National Museum.

Perhaps surprisingly, even as his business continues to market its upscale brand of nostalgia, Cottar thinks they have a point.

Cottar’s family has been very much embroiled in the history of Kenya: his great-grandfather Charles was an American hunter famous for surviving leopard attacks and developing a reputation for befriending tribal communities.

His son took on the mantle and opened a lodge of his own but was gored to death by a rhino. Calvin Cottar himself shows no fear of the bush, happily walking alone for hours without even a gun for protection.

The camp is the latest incarnation of a family business that has seen Cottar men welcoming royalty to hunt on their land for decades – although it is Calvin who orchestrated the revival of these early decadent safaris, but with the shots coming from cameras rather than guns.

Beasts and vintage sofas

A deep-rooted familiarity with colonial Kenya is woven into the way the lodge runs. There are ornate writing desks and four-poster beds in each bedroom, waiters carry silver trays of gins and tonic out to the pool before lunch, and long mahogany tables are laid for dinner, when guests are encouraged to dress up and mingle.

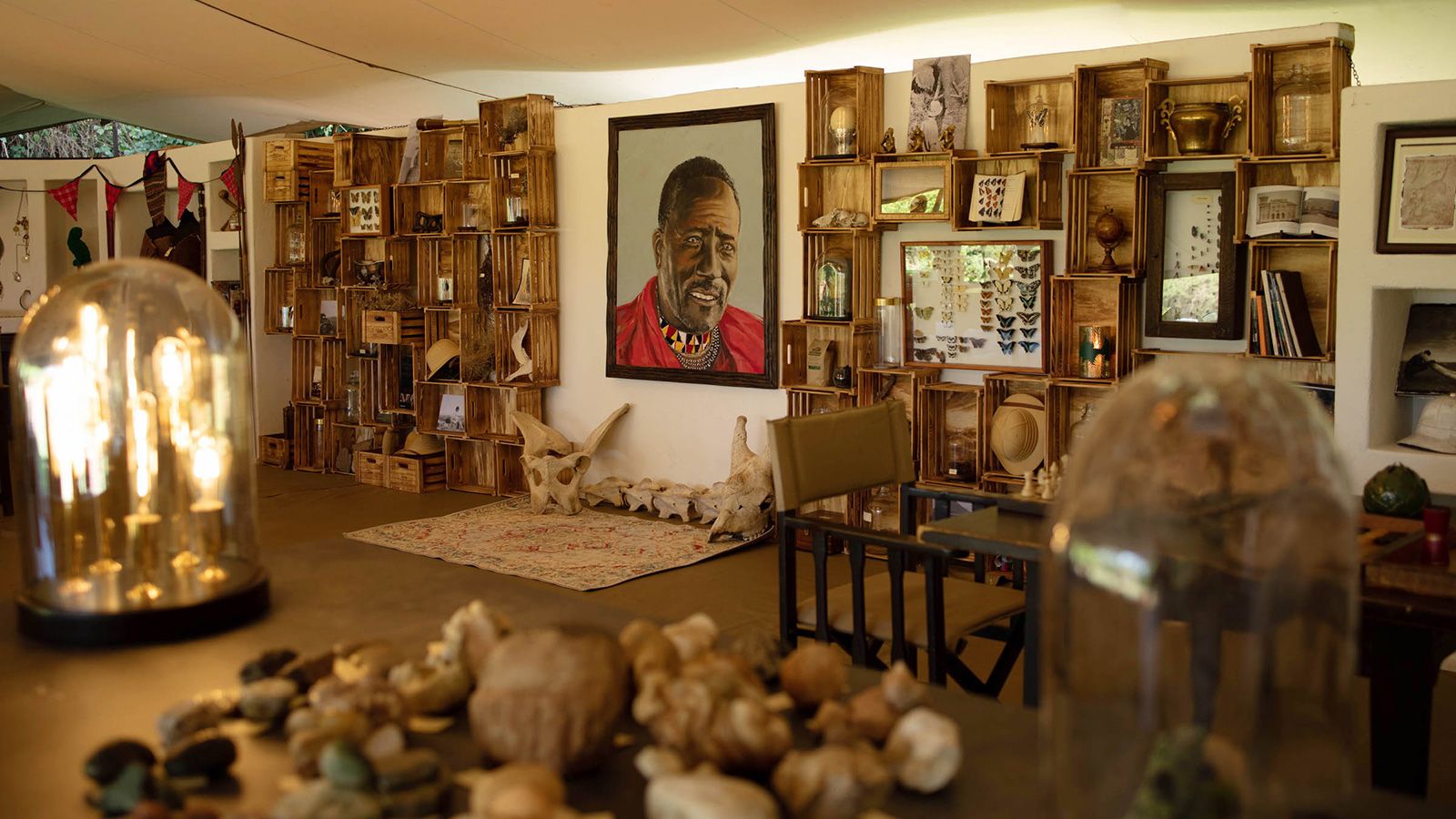

The recently renovated open-front mess tent, meanwhile, is as opulent as it gets with crystal whisky tumblers, oil portraits, vintage mirrors and antique teak dressers.

But despite all the pomp and ceremony, it’s also a place where the bush outside constantly intrudes. At night, guests sit around the fire with local Masai guides – and more often than not a giant eland antelope with tusks that could kill will saunter up to Cottar and start drinking red wine from his glass. Usually he will laugh, take another sip and tell everyone not to get too close as “they’re actually pretty dangerous.”

One recent morning, in and among the vintage Chesterfield sofas, brass gramophones and antique chandeliers, the body of a dead waterbuck antelope was found.

It felt like a scene from an Agatha Christie novel, had she gone through a surrealist phase. The animal was lying in a pool of its own blood while surrounded by first-edition books and leather armchairs.

“Fighting for breeding rights,” Cottar said with a nod, and asked his team to drag it down to the watering hole to see what would eat it. (Answer: hyenas, which cackled that eerie laugh of theirs and left barely a bone undevoured.)

It does all feel deeply reminiscent of an old, largely lost world and Cottar is happy to admit that he too feels uncomfortable by the extent to which colonialism sells.

“White Africans in particular have to change,” he says – somewhat ironically – over tea in the library one afternoon.

“All this 1920s decor is tricky though because there is still such an appetite for it, and the guys who work here don’t mind – it’s just theater for them – but urbanite Kenyans are vehemently anti anything colonial-looking, and I get it.”

Interestingly, despite being well aware of the problems that can arise from capitalizing on this period, Cottar has no plans to change the aesthetic. This is because he thinks the far bigger problem facing Kenya is that of land ownership, and that by attracting high-paying guests to his camp – who in the most part want these Edwardian signifiers – he will be in a better position to transform the way high-end hospitality and local tribes interact.

A war with the animals

At times it sounds like he is calling for an end to people just like him. Ex-colonials still own a surprisingly high proportion of the land here – Hugh Cholmondeley, a British lord, for example, has 48,000 acres of prime farmland north of Lake Naivasha, which he uses for conservation and cattle-breeding – while foreign-owned organizations and hotel groups have bought thousands of hectares around the country’s national parks and turned them into wildlife-focused conservancies.

Cottar is against all of it, arguing that buying the land the Masai have always lived on forces them into subsistence farming elsewhere, and into a war with the animals that eat their crops and kill their cattle.

Wildlife is dying because fences – simple structures made of wood and wire – now cover huge swathes of the Masai Mara. They impede all migrations and are the reason why, even with poaching figures dropping each year, lion and elephant populations are in freefall.

The solution, Calvin says, is biodiversity easements, which sounds complicated but which actually means renting the land from the Masai rather than owning it. This ensures they have a fixed income each month and no longer need to rely on farming to survive. It also means they have an incentive to keep the animals alive rather than poison them, as one dead elephant or lion means less rent in their pockets.

As a result – despite coming from a large landowning family – Cottar himself now owns very little land, having given most of it away. He believes others should follow suit.

Whether this will make him popular with the White community – people whose families, like his own, have been in Kenya since the days of British rule – is not something that keeps him up at night. “Oh they all think I’m completely mad when I suggest they pay rent on their own land,” he says.

His desire to work towards creating a fairer Kenya is also clear within the camp. The entire team is Kenyan, from the camp manager to the highly acclaimed chef. The guides, meanwhile, are all local Masais, some of whom now own the land they work on.

Forward thinking?

Every day, they take his millionaire and celebrity guests out in the strikingly beautiful conservancy that surrounds the camp. It’s a world straight out of an Attenborough documentary, where animals roam free without any human interference – prides of lions with scratches on their faces after fights with buffalo; young cheetahs, fat and glossy in the hot sunshine.

And elephants wherever you turn, posing as professionally as any influencer against mountain backdrops. Often, jeeps are surrounded by breeding herds and while the more life-weary matriarchs stride ahead, curious teenagers surge around the vehicle to get a closer look.

The strong relationships that the family has with the tribes mean their community projects are also impressive; activities, accompanied by Masai guides, include looking for medicinal herbs in the open bush (with a hunter-gatherer tribesman whose life story has had 9.2 million views on YouTube), tracking endangered pangolins and working with a vulture rescue group.

Towards the end of any trip, guides usually insist that guests climb out of the metal safety net that is the jeep and try to understand how the Masai feel living here – and why it is the entire ecosystem that needs protection rather than any individual species.

Stalking out in the bush on foot, standing at the same level as the animals, listening for their footsteps or distant alarm calls, touching the damp leaves and smelling the crushed mint and grass underfoot, is an extraordinary feeling and leaves guests unsure if they are predator or prey.

And whether they are in the most forward-thinking camp in Kenya or on a mind-bending trip back to Britain’s colonial past.