It’s a seven-hour flight across the Atlantic at a bargain price: Low-cost airline Norwegian will jet you from New York to Madrid for $154 one way, taxes included. And the fare isn’t a travel anomaly – the likes of American Airlines and Lufthansa are all fighting for passenger pennies, offering round trip fares between various US cities and Europe for under $400.

But just how are these airlines making a profit on such low fares?

They’re not, says Gerald Cook, adjunct professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. It’s part and parcel of airline costs and ticketing, which Cook, a former airline operations executive and pilot, calls “mysterious.”

“That single inexpensive ticket to Europe is not profitable for any airline but it adds to the total revenue of the flight,” Cook explains.

Low fares don’t pull their weight

Airfare is not based directly on per-seat costs, according to Cook. Total costs to operate a flight include a massive fuel bill, salaries for two or more highly trained pilots and cabin crew, food and cleaning expenses and payments for aircraft with sticker prices of $250 million or more.

“Typical airline schedules are set twice yearly. The resulting costs to offer that schedule are virtually fixed,” he says. “Fuel prices might change, but that’s not something airlines control.”

Ryanair, the famed European budget carrier, boasts that its average fares do not actually cover the cost of flying the passenger.

It’s very profitable nevertheless, making up the difference through baggage and seat selection fees and sales on board – all higher-margin products than the seat itself. The airline flies as frequently per day as possible so that it can charge for these extras often; long-distance carriers plying the Atlantic cannot.

“The real variability is not cost, it’s revenue,” Cook explains. “The airline’s objective is to maximize revenue for a particular flight on a particular day, based on expected and actual demand.”

What are the world's safest airlines for 2019?

Cook estimates that around 10% of all seats are available as a basic economy fare.

That means that on a typical wide-body jet to Europe, around 30 seats are available at a cut-rate price. Once those tickets are sold, the fares will generally increase as the travel date approaches.

Bargain hunters beware: “If you try to book an economy seat very close to departure, you might pay 10 times the basic economy fare,” Cook says. He advises travelers to book as soon as they have a travel date in mind.

The lucky math

“If the airlines did not offer low fares to entice passengers – albeit with significant restrictions – the seats would go unsold and generate no revenue. They are much better off selling some seats at low fares,” he said.

But not too low and not too many, says Henry Harteveldt, founder of Atmosphere Research Group and an airline industry expert. “No airline will discount more than they need to. And no vice president of revenue gets a bonus for discounting fares.”

Harteveldt says the objective of established airlines is to sell just enough basic economy fares to compete with the low-cost competition and also to push passengers into the higher fare classes within economy, premium economy and business.

The airlines use complex software to make dynamic price adjustments based on historical data, competitor fares, expected and actual sales for a particular fare class on a flight, along with some oversight by internal teams.

“One software provider analyzes more than one billion fare combinations between London and New York considering different fare classes, airlines and seats on individual flights flying the route,” Harteveldt says.

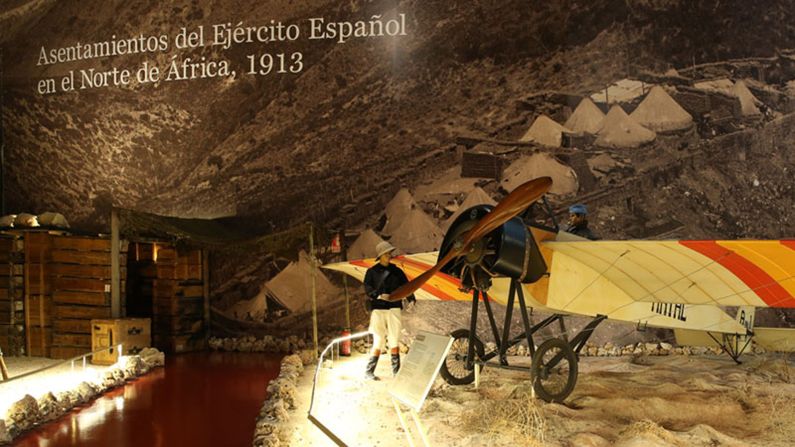

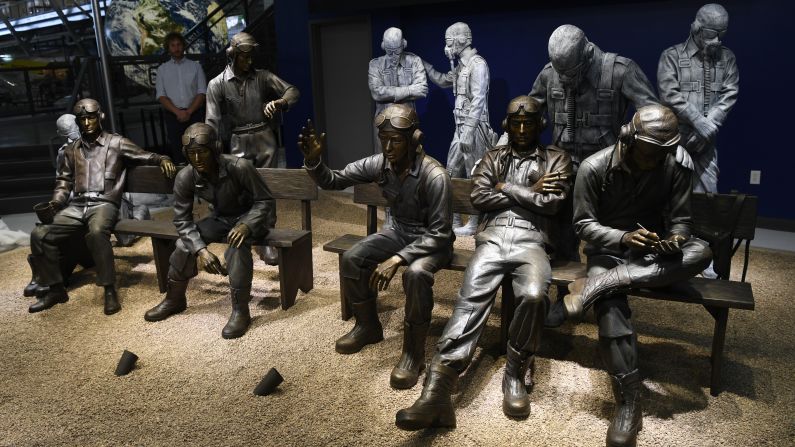

Top aviation museums around the globe

‘Healthy demand’

Are we in a golden age of low fares?

Harteveldt thinks so. “Fuel prices have been reasonable. There is healthy demand for air travel in the US and Europe and even relatively healthy demand in Latin American and Asia.”

“Fares go down where a market has a price-based competitor and a lot of capacity to meet the demand,” Harteveldt explains. He notes that when Southwest enters a market the fares fall, citing the example of its recent entry into the Hawaiian market where some fares are as low as $49 from the West Coast. Hawaiian Airlines and United, its major competitors, “will respond in a controlled, disciplined manner,” he says.

The same logic applies to transatlantic routes. “Even if you don’t fly Norwegian, thank them,” Harteveldt says. “They may cause lower fares to be offered by your preferred airline.”

JetBlue is one of the latest US airlines to announce that it’s going transatlantic: It’ll start running flights from London to New York and Boston in 2021.

Cook agrees. “On the North Atlantic routes, there is lots of competition and there will continue to be even as airlines come and go. Generally, those fares are here to stay.”

![<strong>3: Delta Airlines</strong>: Delta jumped four spots this year in TPG's ranking. "Their frequent flier program isn't as strong as the other two [United and American], considering it's a better run airline, it runs more smoothly and their employees are generally happier," says Kelly.](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/180306104820-delta-airlines.jpg?q=w_3930,h_2516,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)