It seems so eternal, doesn’t it?

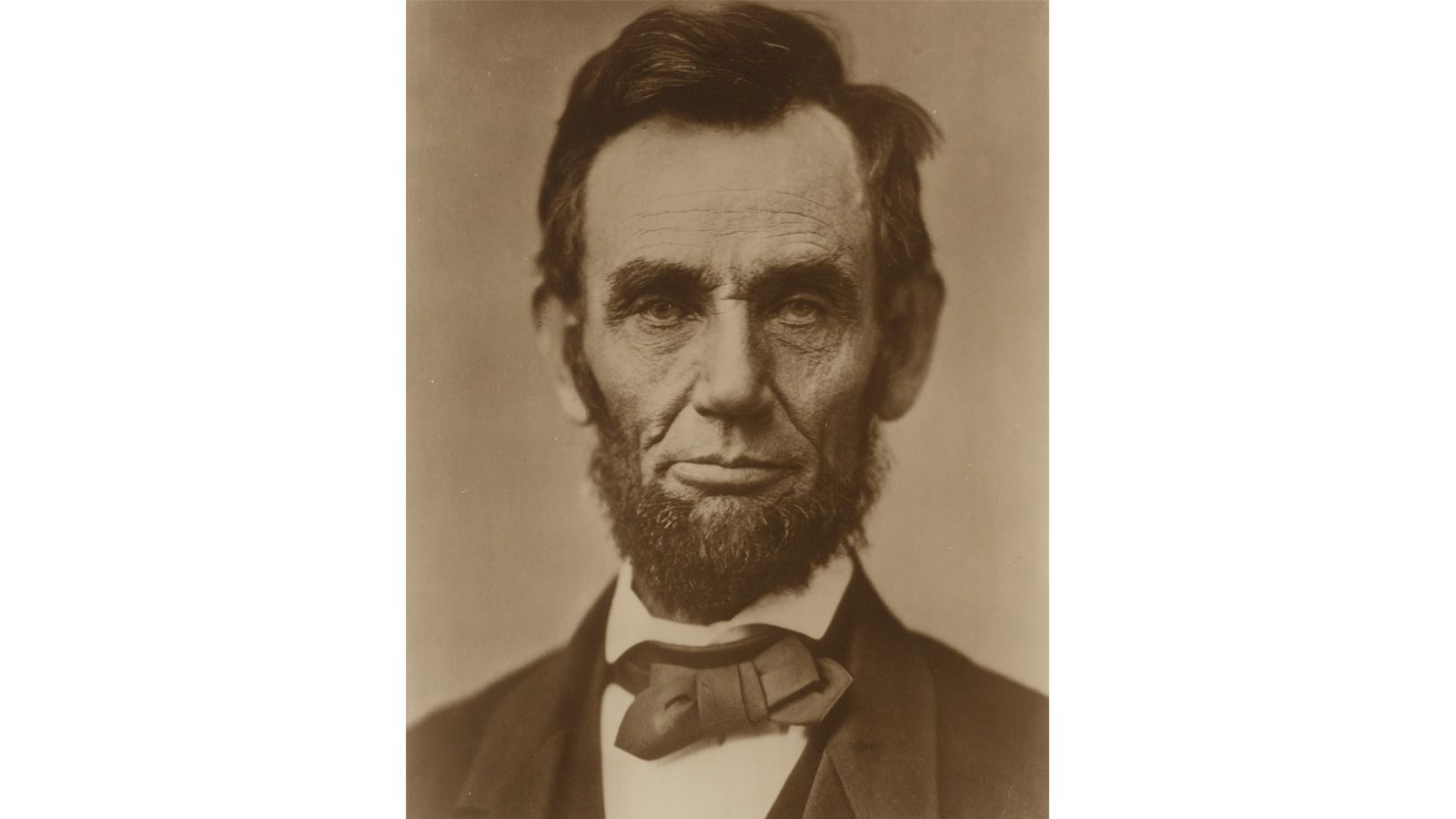

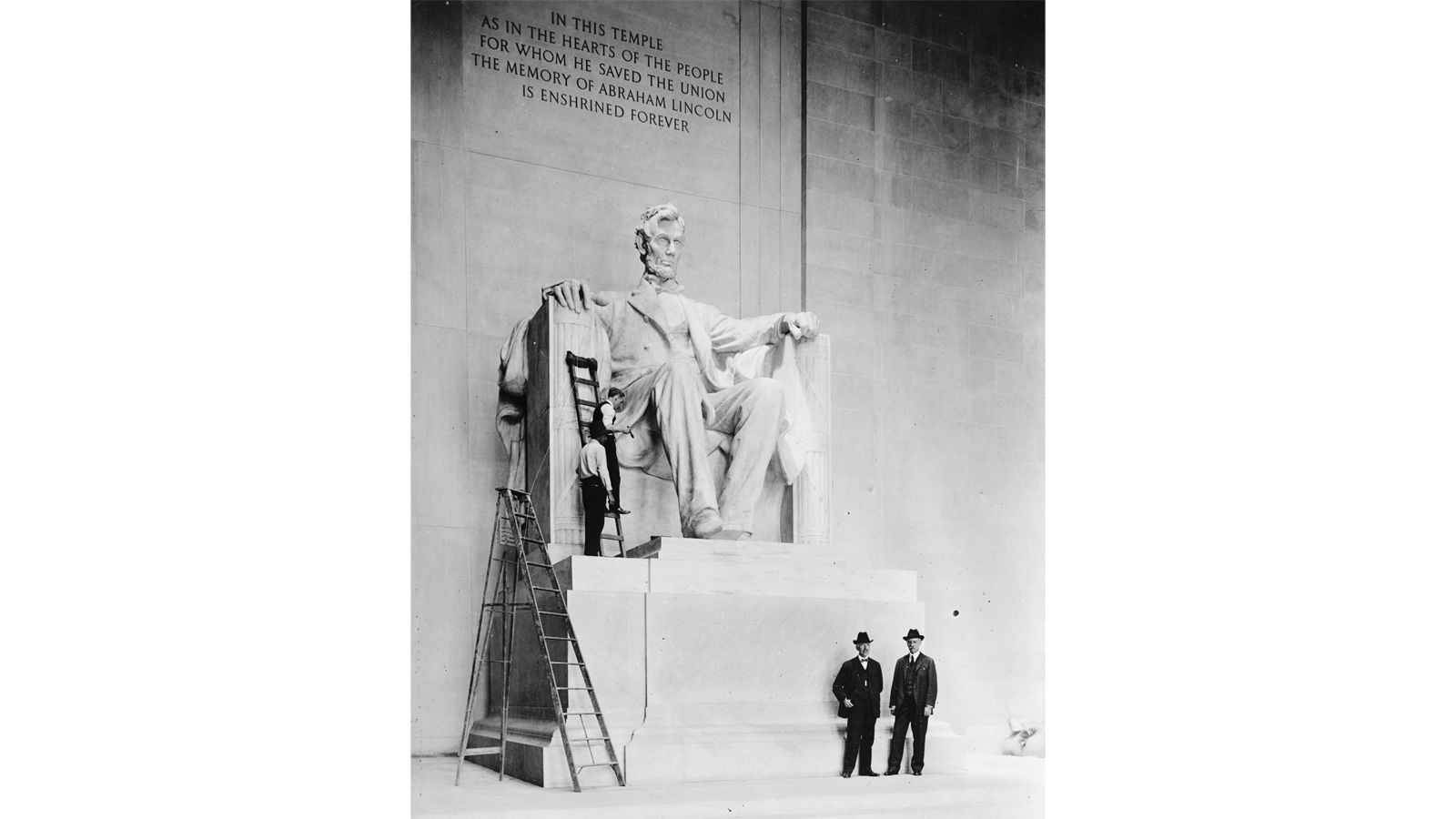

The gleaming white marble. The massive columns. The huge statue of a man sitting straight up with purpose and solemn dignity. The face is wise and weary and staring resolutely ahead. The hands – one clinched and the other relaxed. The inscribed speeches calling us to find our better angels and forge ahead.

Surely it’s been there forever, reminding us and humbling us and guiding us.

Yet the Lincoln Memorial has been with us just 100 years. It opened on the National Mall, the Potomac River flowing behind it, on May 30, 1922. That was 57 years after President Abraham Lincoln was felled by an assassin’s bullet scant days after the Civil War had officially ended.

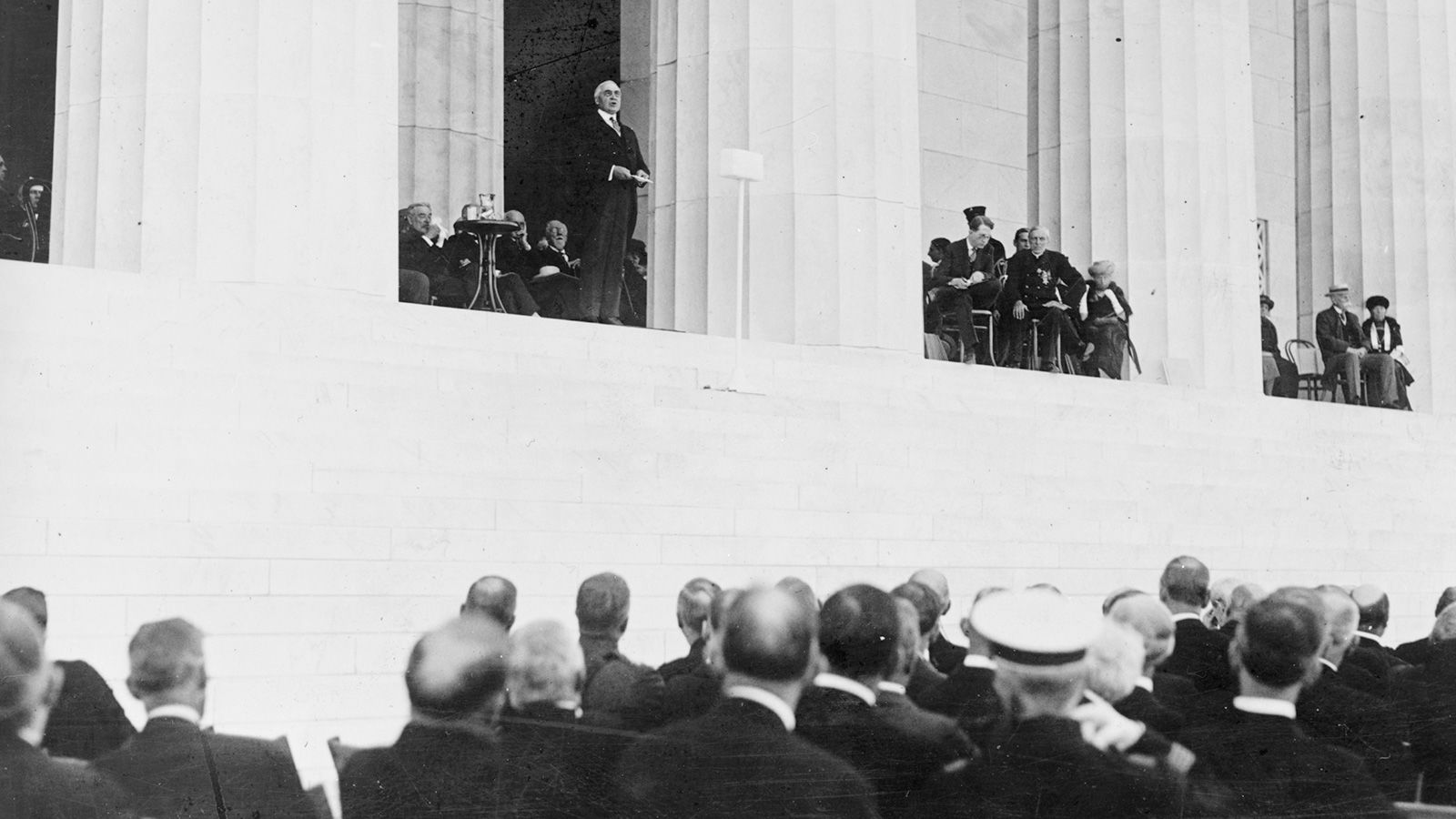

About 50,000 people attended the opening ceremony, according to the National Park Service. As many as 2 million people listened on the radio, the internet of its era.

Since then, millions of visitors – US citizens and people from around the world – come yearly to bask in the majesty of the ancient Greece-inspired temple and to glean some wisdom from the 16th president of the United States.

In November 1981, I was one of those people.

‘Remember this moment’

It was a surreal experience. I had ventured out of the Deep South only once before in my life when I found myself looking up awe-struck at Lincoln’s statue.

My university’s journalism fraternity had sponsored a DC trip during my sophomore year. Much of that trip is lost to mists of time now. I even had to consult a college friend to nail down the time for certain.

But the memory of my first visit to the Lincoln Memorial itself remains as clear as the cold, moonlit night I made it on.

Our hotel wasn’t far away, and I sneaked away from the group to see it. Hardly anyone else was there. Being in near solitude with no distractions enhanced it all.

I wasn’t prepared for what I saw. Or felt.

Flooded in light at night, I was moved by the beauty. But it was the inscriptions that emotionally overwhelmed me – especially the ending lines of the Second Inaugural Address on the north chamber wall.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan ~ to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

We were facing our own troubles in the fall of 1981. The United States was in a deep recession. The threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union was a constant underlying anxiety. And assassination was in the air again – Anwar Sadat of Egypt had been killed just weeks earlier, and President Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul II survived attempts on their lives in the spring.

It was easy to feel worried about the future – mine, the nation’s and the world’s. But there sat President Lincoln, carrying burdens few would ever understand during America’s greatest crisis, pointing the way forward.

I paused on the way out to sit on the steps of the memorial, all alone but feeling the arms of my country around me and almost giddy with a hope bolstered by youthful optimism. A bright moon lit up the mall with the Washington Monument and US Capitol in the background. And I told myself, “Remember this moment. Remember this moment. …”

The nation in 1922

Lincoln was a controversial figure, especially in the defeated South.

Just two years after his death, Congress passed the first of many bills to create a memorial, according to the National Park Service. But only in 1911, when Congress formed a new Lincoln Memorial Commission, did things really get moving.

A groundbreaking took place in 1914, on land decried by some critics as a swamp.

Finally, the memorial opened on May 30, 1922. Present were principal speaker Dr. Robert Moton, president of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, who addressed a mostly segregated crowd; Supreme Court Chief Justice (and former president) William Howard Taft; President Warren G. Harding; and Robert Todd Lincoln, Lincoln’s only surviving son, according to the NPS.

I wonder what personal emotions and thoughts they might have had looking at the brand-new structure so long in the making.

The memorial is of Neoclassical design and based on the Parthenon in Athens, Greece. Maybe that gives it that air of permanence.

According to the NPS, “It consists of a main level on a high raised basement with a recessed attic story above. The building stands in splendid isolation in a landscaped circle at the west end of the National Mall.

“A colonnade of 36 Doric columns, representing the number of States in the Union at the time of Lincoln’s death, surrounds the memorial chamber.”

Inside, the 19-foot-high statue towers over the visitor, much as his legacy towers over the country.

Americans in May 1922 were in a period of progress and pushback. The United States enjoyed victory with the Allies in World War I, but communists were on the verge of officially forming the USSR.

Women had earned the right to vote less than two years earlier. And while slavery had been abolished, Jim Crow segregation had sunk deep roots into the country in its place.

America was one nation again, but much work remained.

The next 100 years

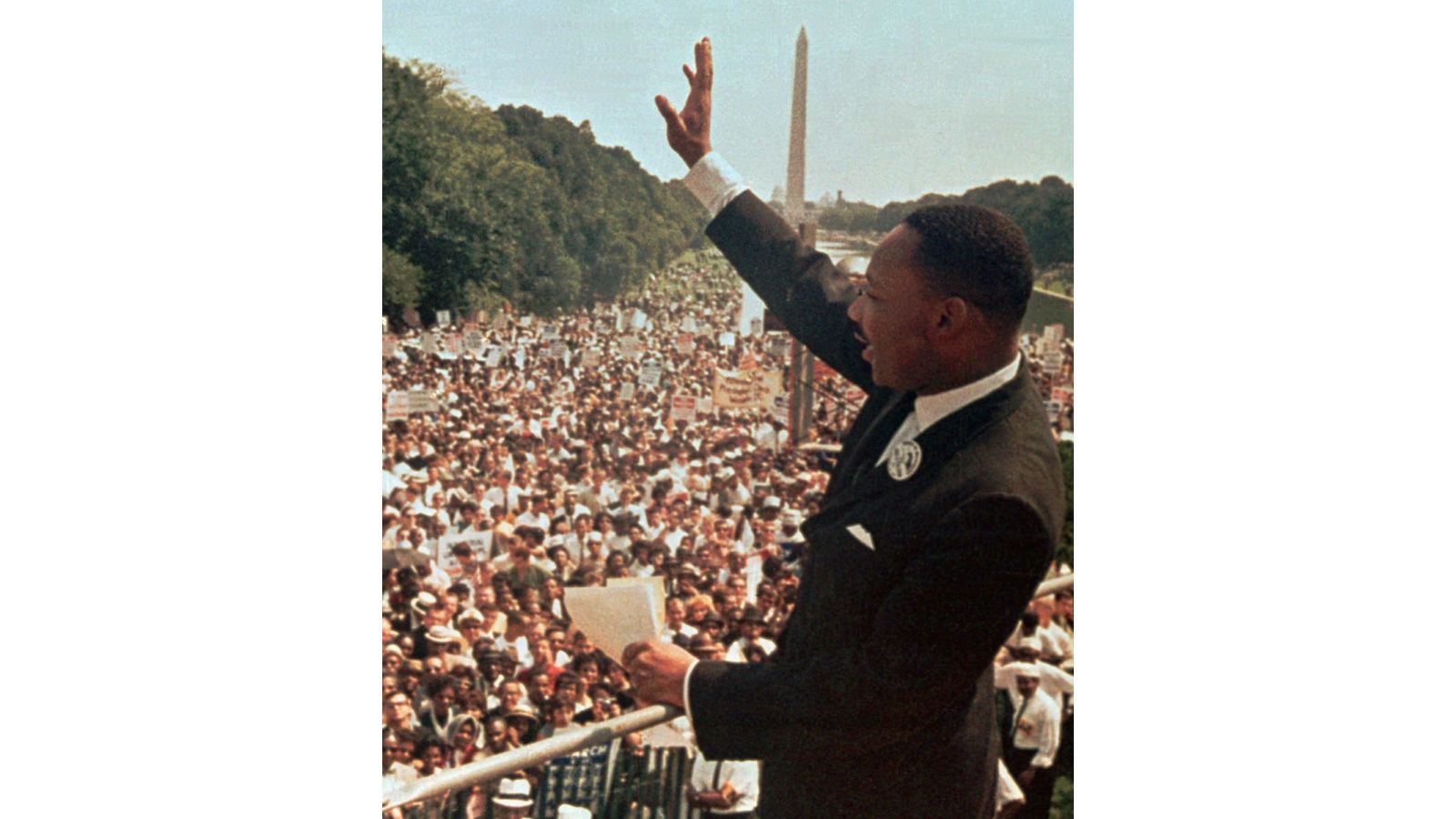

In the 100 years since it opened, the Lincoln Memorial has been the backdrop of national celebrations and witness to pivotal and emotional moments in US history. That’s especially true in the realm of civil rights.

It was there that contralto Marian Anderson sang in 1939 to a crowd of about 75,000 after the Daughters of the America Revolution denied her request to rent facilities at Constitution Hall.

It was also there that Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, electrifying the nation and inspiring generations.

And as we hit the 100th anniversary day on May 30, which lands appropriately enough on Memorial Day, our troubles remain.

A climate crisis that Lincoln could never imagine hovers over us. Moscow is once again an enemy. The scourge of inflation is back. Violent crime is up. The pandemic might not be done with us yet. And from a church in Charleston, South Carolina, to a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, slavery’s hateful and murderous legacy continues more than 150 years later with no end in sight.

It sure feels like a nation divided, and I feel more worried about the future than ever. Youthful optimism has been replaced some 40 years later with hard-earned disappointment and seemingly justified pessimism.

Still, we will go to the memorial. And hope. What else can we do? Give up? Lincoln didn’t. Millions will continue to ascend those steps, and some will find wonderment and insight. On the south chamber wall are these words from the Gettysburg Address:

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us ~ that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion ~ that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain ~ that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom ~ and that government of the people by the people for the people shall not perish from the earth.

That durable memorial, born of crisis and war, is a bastion of hope. Maybe our solutions rest there. If not solutions, at least the encouragement to endure fiery trials.

As President Harding said in his 1922 speech: “This memorial is less for Abraham Lincoln than those of us today, and for those who follow after.”

How to visit the Lincoln Memorial

It is open 365 days a year, 24 hours a day. The NPS says “early evening and morning hours are beautiful and tranquil times to visit.”

The memorial is at the western end of the National Mall, a two-mile (3.2-kilometer) walk from the US Capitol with the Washington Monument in between the two.

The nearest metro stations are Foggy Bottom (23rd Street and I Street NW) and Smithsonian (12th Street and Independence Avenue SW). Click here for more details.

Forrest Brown graduated from the University of South Carolina in December 1983 with a bachelor’s degree in journalism, and he started working with CNN Digital in 2008.