Editor’s Note: CNN Travel’s series often carries sponsorship originating from the countries and regions we profile. However, CNN retains full editorial control over all of its reports. Read the policy.

Story highlights

Vietnam has three citadels listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites and the latest -- and strangest -- is the Citadel of the Ho Dynasty

Ho Citadel, the capital city of the short-lived Ho Dynasty, is made up of four city walls surrounding farmland

Developing tourism may mean stopping agricultural activities and could affect locals' livelihood

You might expect a communist government to distance itself from its imperial past, but the Vietnamese regime has seen the value in celebrating the country’s bygone emperors and promoting its ancient citadels as tourist destinations.

Since 1993, eight locations in Vietnam – including three citadels – have been designated as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO, with another seven awaiting formal classification.

Many of these sites are of great natural or historical significance, such as Ha Long Bay and the complex of monuments in Hue. But the citadel to most recently acquire UNESCO’s seal of approval (in 2011) is the almost unknown Ho Citadel, situated in a remote backwater of Thanh Hoa Province, around 150 kilometers south of Hanoi.

The choice of the Ho Citadel for such a prestigious honor is strange for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, the Ho Dynasty lasted just seven years (1400-1407), a mere drop in the ocean of Vietnam’s turbulent history.

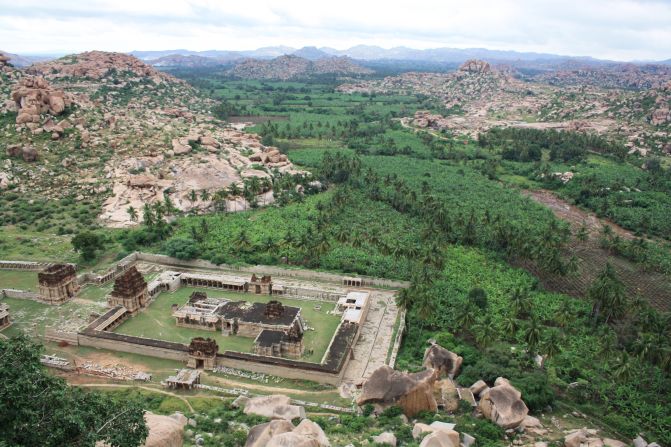

Secondly, the citadel is empty. That’s right – no palaces, no temples, no monuments – just four walls surrounding nothing but farmland. However, according to UNESCO, the citadel represents “an outstanding example of a new style of Southeast Asian imperial city.”

Intrigued by the notion of discovering a medieval city in the Vietnamese countryside, I decide to explore the empty citadel.

What’s left of the citadel

I contact a friend, Xuan, who lives in Ninh Binh, about 60 kilometers east of the citadel. We arrive at the north gate of the Ho Citadel, pay the 10,000-dong (about 50 cents) entrance fee and scramble up the grassy banks to take in the panorama from the top of the wall.

Xuan tells me the location was chosen according to the principles of feng shui, pointing out the Don Son and Tuong Son mountain ranges that protect the valley, and the Ma and Buoi Rivers that flow on either side of the citadel.

Despite the bucolic view, my attention is drawn to the massive blocks of stone in the wall. They’re slotted together without any mortar; some measure several cubic meters. These 600-year-old walls, which stretch almost a kilometer on each side, are remarkably intact, and the four vaulted gateways stand as sturdy as ever.

Inevitably, parts of the wall have subsided or become overgrown with grass and shrubs, but that somehow adds to the site’s mystique. Encompassed within the walls is a timeless scene of corn and rice fields, ponds and dirt tracks – a picture of abundance and self-sufficiency.

Short history of Ho Dynasty

“So how come the Ho Dynasty was so short-lived?” I ask Xuan about this lesser known page of Vietnamese history.

In the late 14th century, he explains, the Tran Dynasty was in disarray, and Ho Quy Ly (aka Le Quy Ly), a regent in the court of Emperor Tran Thuan Tong in Thang Long (Hanoi), laid plans to usurp the throne. In 1397, he had this new citadel built, a task that apparently took only three months – an amazing feat of engineering in an age before power tools.

When Ho invited the emperor to inspect the newly built citadel, initially known as Tay Do (“Western Capital”), he imprisoned then executed Tran Thuan Tong, establishing himself in 1400 as first emperor of the Ho Dynasty. After ruling for just a year, Ho Quy Ly relinquished the throne to his second son, Ho Han Thuong, who reigned for a mere six years, after which the Ho were overrun by the Ming from China.

Despite his brief tenure in Vietnam’s top job, Ho Quy Ly was responsible for the introduction of paper money and limits on land ownership, as well as opening ports to foreign trade and expanding the education curriculum to include subjects like mathematics and agriculture.

We drive along the dirt road through the empty citadel toward the south gate, the citadel’s main entrance, which is pierced by three arches, compared to just one in the north, east and west walls. We step into a bamboo hut outside the south gate where the walls are lined with illustrations of elephants and horses dragging huge slabs of stone from a quarry, bamboo rafts carrying the slabs downriver and men and beasts hauling the finely cut stones into place on the wall.

From the bamboo hut we stroll into an almost empty museum where a few artifacts such as stone balls for use with slingshots and a terracotta phoenix head have been recovered from the site.

Farming vs. tourism

I leave Xuan chatting to the curator and clamber up on top of the south gate, where I imagine the empty citadel bustling with its 15th-century inhabitants as they throng the markets, palaces and temples that once stood within these impenetrable walls.

Snapping back into the present, all I see is a file of school kids cycling through the rice paddies on their way home from school.

Xuan comes out of the museum, and tells me of the curator’s concern for the future of the citadel. As part of the deal with UNESCO, Vietnam is committed to protecting the citadel’s heritage, which means preventing any new building from spoiling the view, and terminating agricultural production, such as rice farming, inside the citadel.

Nguyen Xuan Toan, deputy director of the Center for Conservation of Ho Dynasty Citadel World Heritage, told Viet Nam News, “As the households possess land use rights, they continue to build houses and other structures and that causes difficulties in protecting the citadel.”

He also explained that plowing, raking and digging irrigation ditches within the citadel has exposed archaeological relics and has a negative impact on the underground architecture at the site. At present, it looks like local farmers will have to sacrifice their land rights if their country’s leaders are determined to develop the citadel as a tourist attraction.

As we ride away, I wonder what Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam’s national hero, would make of this conundrum.

Ron Emmons is a British writer/photographer who travels regularly throughout Southeast Asia from his base in Chiang Mai, Thailand. He writes for publishers including National Geographic and Rough Guides.