When Maria-Elena Grant stops by the Cubbyhole in Greenwich Village after work for a drink with friends, she can’t help but remember the battles she’s fought along the way.

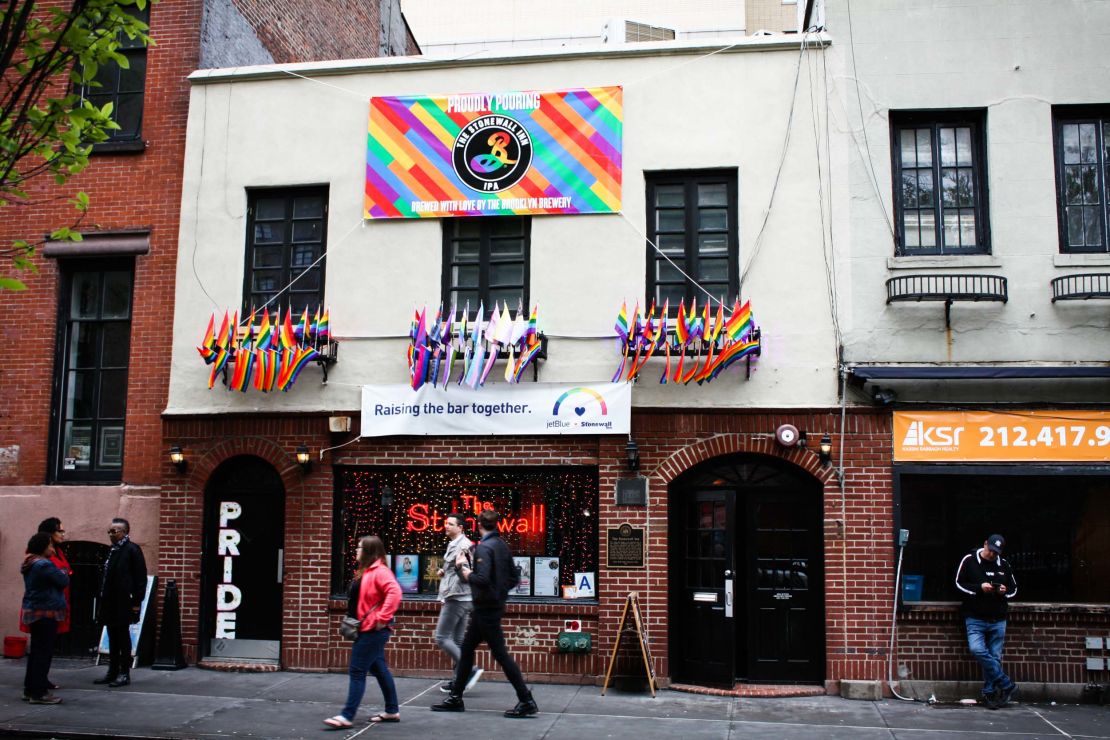

A longtime hangout for lesbians and their friends, the Cubbyhole is one of the few lesbian bars in a neighborhood where the modern gay rights movement got national attention after a police raid at the nearby Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969.

The first pride march took place the following year, as LGBTQ people in New York City marched to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall uprising – and to fight for their rights.

“The gay pride parade wasn’t a parade,” Grant said. “It was a march, it was like a civil disobedience, it was a demonstration. It wasn’t like having a fancy corporate float and all this money … It was a civil rights action.”

A neighborhood in transition

As New York marks the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising this pride weekend, welcoming WorldPride to the city, the neighborhood where Grant and other LGBTQ people once gathered in force has gone through several decades of transformation.

Just as critics of the main Pride parade say corporate sponsors have “pink-washed” its political roots, many longtime New Yorkers say gentrification has made real estate in the Village out of reach for all but the most affluent. Gone are many of the bars, restaurants, bookstores and the massive St. Vincent’s Hospital that took care of AIDS patients when no one else would.

For those who believe pride has become too frivolous and commercial, an alternative Queer Liberation March and Rally is being held the same day as the World Pride celebration.

Past and present are still alive for Grant, who remembers the neighborhood where she visited with her then-girlfriend for the first time when she was just 20 and saw other people just like her – lesbians, people of color, immigrants, people who didn’t fit into the majority culture.

She came out as a teenager

Grant, now 55, was born in London, England, but moved with her mother and brother to New York after her father died in 1978, to be closer to her mom’s sister. She met her first girlfriend when she was 16 at an audition for a church production of “Jesus Christ Superstar.” (Grant’s girlfriend got a part, but she did not.)

Over the course of the next 40 years, the personal became political for Grant, as she joined Lavender Light Gospel Choir and was introduced to LGBTQ politics; helped create BLUES (Bronx Lesbians United Eternally in Sisterhood), a Bronx social group for lesbians; took to the streets to fight AIDS; and started working at a production company that turned out LGBTQ films.

She fell in love with her partner, Cyrille Phipps, in 1992, and they’ve been together ever since. Still involved in running Lavender Light, Grant is now senior manager for operations and special projects at The New School in the Village.

Greenwich Village is still home

Even though she and Phipps live in Brooklyn, the Village is still a place where Grant and her friends gather.

Today she walks past the “Gay Liberation” (1980) statues by sculptor George Segal in Christopher Park, protected in 2016 along with the Stonewall Inn as a National Park Service site, by then-President Barack Obama.

The Duplex, a piano bar and cabaret, is still there, although in a different location, but the Duchess lesbian bar is gone, replaced by a Starbucks.

This is where she would get a drink at the Cubbyhole or dance until dawn at Garbo’s lesbian bar or Cinnamon Productions monthly dances for women of color at Octagon (a gay men’s club), followed by chicken and waffles at the Pink Tea Cup, a soul food restaurant.

She could buy books at LGBTQ-focused bookstores like Oscar Wilde, now gone, and the bookstore also sold Lavender Light concert tickets and CDs.

It’s where she would visitSt. Vincent’s Hospital to say goodbye to her gay male friends dying of AIDS, and head out into the streets to protest for the resources to find a cure.

Gentrification and assimilation

There’s a smaller emergency room hospital in its place, and The New York City AIDS Memorial Park at St. Vincent’s Triangle, a memorial to those lost to AIDS, but Grant still feels that loss keenly.

“I think there are two things that broke up the community,” she said. “One is obviously the money made from gentrification that just simply took over properties and made them into something else.”

“One of the (other) things that started to happen with us is assimilation, because when you’re fighting for acceptance and when you’re fighting to belong, after a while you do start to make progress,” she said.

That means gay-themed books can be found at Barnes and Noble, and now Amazon, and LGBTQ couples can hold hands at restaurants and bars that serve a wider community.

She mourns the loss of some of those institutions even as she celebrates the progress the LGBTQ rights movement has made.

The Village is still gay (and lesbian and bi and trans)

Other aspects of the village’s storied LGBTQ significance remain, and Grant and her friends have stayed connected to those places.

The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center, now on West 13th Street, is Grant’s starting point for any LGBTQ newbies to New York City. Much sleeker in appearance now, even with a coffee bar inside, the Center still offers one-stop shopping for social services, 12-step and other groups. (Grant once worked at the Community Health Project, which was once based at the Center. It’s now the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, with locations in Manhattan, the Bronx and soon Brooklyn.)

She has sung with Lavender Light Gospel Choir, where she serves as co-chair and chorus manager, for nearly 30 years, focusing on her belief that God is love, and love is for everyone. Since Grant grew up in an accepting Church of England, she was determined to hold onto her faith in a more divisive US religious environment. (They are scheduled to sing during Pride weekend at the Center.)

The choir sings at the Good Friday service at Metropolitan Community Church’s New York City location, which was founded in 1972 when many mainstream churches would not welcome members of the LGBTQ community. (The denomination was founded in 1968.)

And she’ll still head to the Cubbyhole or Henrietta Hudson for a drink, a spot that charges less than the typicalNew York prices for its drinks, where baby dykes and veterans of the gay civil rights movement hang out, listen to tunes from the jukebox and talk about the tension between progress and remembering where you came from.

‘That’s progress’

In Brooklyn, where she lives, she and her friends will head to Ginger’s, a longtime lesbian bar in Park Slope, to play pool and hang out.

Grant marvels at the growth of the LGBTQ rights movement and all the progress the activists within the movement have made.

“We, for instance, can sit here on a Sunday afternoon and have this drink with each other and not worry that the police are going to come and raid this bar,” she said. “That’s progress.”

“We can get married. Undoubtedly, all of that is amazingly true.”

She hopes that some of these important institutions will survive the waves of gentrification and assimilation, as the Cubbyhole seems to have done.

“When I come in here, it almost feels like the LGBT bar that Cheers would be if it was an LGBT bar,” she said.

“I feel at home right away. And at the end of a long day sometimes you want to just have a drink with your people. So, it matters to me that there are pockets and businesses that are specifically for the LGBT community.”

‘People need to remember’

As they gather at the Cubbyhole, Grant and her friends hope that other lesbians, gay men, bisexual and transgender people – both white and people of color – will remember the battles long and hard fought. Those battles for civil rights and for a cure for AIDS are not over, they say.

“Despite all the strides that we’ve made, and the fact that we’re in a much better place now in so many ways, we had to fight to get here. And there was a way that we got here, and people need to remember how that happened.”

And there’s still a fight, she says, noting all the recent violence against transgender people, including the murders of Chynal Lindsey and Muhlaysia Booker in Dallas.

“It’s not like violence against us has stopped,” she said. “It’s not like we’re completely accepted.”