It was supposed to be the world’s largest airport, a glamorous intercontinental hub for supersonic airliners with six runways and high-speed rail links to surrounding cities. But today, it’s little more than an airstrip in the middle of nowhere.

The Everglades Jetport, as it was called when the project launched in 1968, started its life right at the end of the Golden Age of air travel, when plane cabins were filled with the smoke of cigars and the clinking of silverware.

Concorde was about to make its first flight, while Boeing was working on an even larger and faster supersonic passenger plane, the 2707.

With a high projected demand for faster-than-sound travel, South Florida emerged as an ideal spot for a hub, because the dreaded “sonic boom” that made these planes unwelcome guests inland could happen harmlessly over the open ocean.

But it wasn’t to be.

Commercial aviation was about to enter a different age, and environmental concerns led to the cancellation of the grand plan for the Everglades Jetport after only one runway had been built.

Now, that lone runway functions both as a training ground and a nostalgic reminder of a dream that never materialized.

Swampland

Today, the airport is known as Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport and is operated by the Miami Dade Aviation Department, which manages four other airports in the area, including Miami International – the third largest in the US for international passenger traffic.

It’s very different from what the Everglades Jetport – which was also known as the Big Cypress Swamp Jetport – was meant to be. “Some people think it’s abandoned, but it’s not,” says Lonny Craven, who manages the airfield for the Miami-Dade Aviation Department. “Right now, due to restrictions, we only have it open from eight o’clock in the morning till 5:30 at night.”

In the original plan, the Jetport was supposed to be five times the size of New York’s JFK and handle futuristic supersonic airliners carrying up to 300 passengers each.

To build it, the Dade County Port Authority purchased 39 square miles of uninhabited swamp land, 36 miles west of the Miami business district and just six miles north of the Everglades National Park.

“They wanted to put it smack dab in the middle between Monroe County, Dade County, Collier County and Palm Beach County, for easy access,” says Craven.

A planned 1,000-foot-wide road and rail corridor would link the Jetport to both the Atlantic Coast and the Gulf of Mexico.

But environmental concerns began to arise soon after construction started.

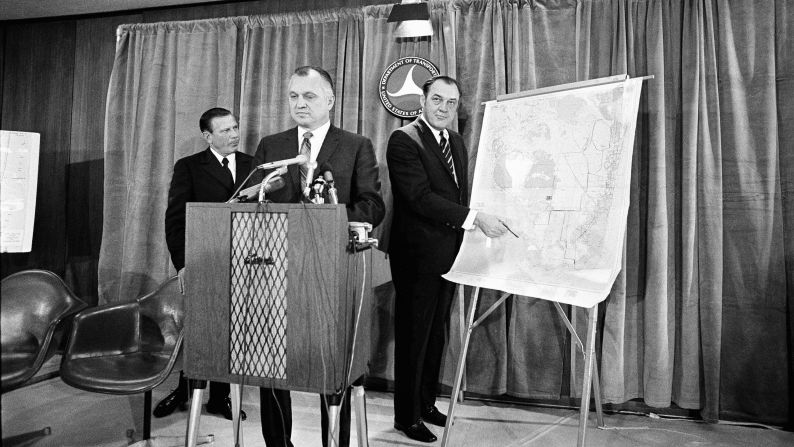

A 1969 report stated that the project would “destroy the South Florida ecosystem and thus the Everglades National Park.”

Backed by local residents and activists, the report led to the Everglades Jetport Pact, which in 1970 brought all construction to a halt.

“The joke was that they were paving the runways on the backs of alligators,” says Craven.

Touch and go

In 1971, the Boeing 2707 project was canceled before a prototype was even finished, and the dream of a US-built supersonic passenger plane died with it.

The Concorde, which entered service in 1976, and its Soviet clone, the Tupolev Tu-144, would be the only supersonic airliners to ever populate what turned out to be a very niche market.

At that point, rather than trying to relocate the Jetport, the whole idea was just abandoned.

What had been built of the airfield never opened to passenger traffic, but its only runway – which is 10,499 feet long – became popular with pilots in training, who took advantage of the remote location and the absence of any other structure in the area. “It was used a lot through the 1970s, the 1980s, and probably into the mid 1990s, by airlines to go out there and do touch and goes,” says Craven.

A “touch and go” happens when a plane lands and takes off again before coming to a complete stop, and it’s a common way for pilots to quickly accumulate practice for these crucial aspects of flying. “With the advent of flight simulators and the high cost of jet fuel, the usage decreased, but we still get practice military flights, mostly from the US Coast Guard, and small private aircraft.”

No landings

Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport – whose airport code is the catchy TNT – does not have a terminal, just an office inside a 2,000-square-foot trailer.

The site is usually manned by four employees who perform maintenance and also provide security, but there is no firefighting or refueling equipment, and proper landings are not permitted outside of an emergency.

“We heard rumors that if the Space Shuttle had to make an emergency landing, it could go there,” says Craven.

There have been attempts to use the facility beyond touch and goes. The runway has seen some high-speed car racing, because it allows fast cars to reach their top speeds. And there was a plan to organize an air show, but that would have required widening the road to the airfield to support incoming traffic, and no new construction is permitted.

Today, the area surrounding the airport is part of the Big Cypress National Preserve, and home to wildlife such as alligators, deer, herons and bears.

The area that the airport also owns, but is undeveloped swamp, is 26,000 acres. That’s how big it could have been. “Miami International Airport is 3,320 acres,” says Craven.

“It was supposed to be the airport for tomorrow.”