As millions of refugees flee the bloody chaos in Iraq and Syria, English builder Andrew Drury is preparing to make the opposite journey – for a vacation.

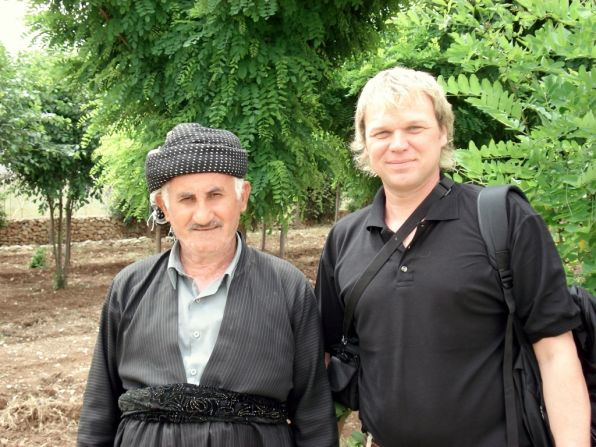

Drury, 50, has a route traced out across the Kurdish-held territories, which runs close to the frontline with ISIS.

“It’s a difficult question – how much risk to take?” he ponders. “You can go right up with the Kurdish troops fighting beyond Mosul. I want to see the Yazidis again… to see if the tribe I met are still alive.”

The Englishman has fond memories of Yazidi hospitality from a previous stay, during a previous war.

It was one of his favorite trips.

Looking for adventure

For more than 20 years, Drury has led a double life.

He’s a husband, father and the owner of a successful construction company in rural Surrey, a short drive from London.

But his passion lies in visiting the world’s most dangerous destinations, and his appetite is insatiable.

The flame was lit on a safari trip to Uganda, which took a strange turn when Drury accidentally crossed a border into war-ravaged Democratic Republic of Congo, and was forced to flee a machete-wielding farmer.

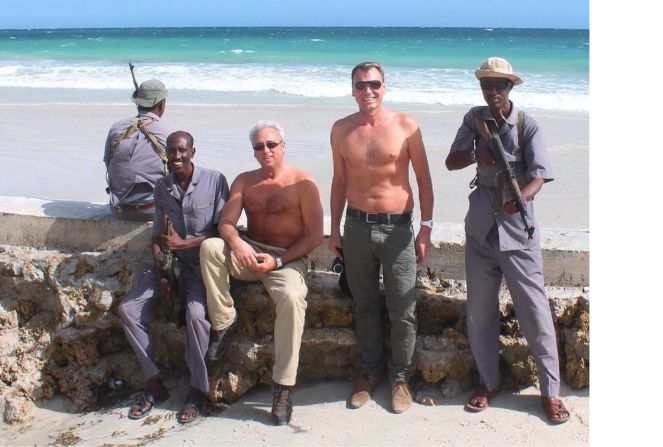

Since then, the builder’s travels have taken in downtown Mogadishu and the insurgent heartlands of Afghanistan.

He says he’s dodged Russian soldiers in the bombed out ruins of Chechnya, infiltrated a Ku Klux Klan militia, played golf in Pyongyang and stayed with a former headhunting tribe in Myanmar.

“It’s risk and reward,” Drury explains. “The reward is that you see more, and you learn more. We’re not born to do nine to five jobs. You have to explore a little bit and try to understand the world you’re living in.”

There’s an element of thrill seeking, Drury admits, but his attitude has changed over time. At first he would travel with a cousin and the two would dare each other to take risks.

But in recent years he has traveled alone, and become closer to local communities.

He’s now the sponsor of a basketball team in his favorite city, Mogadishu, and returns to watch it play.

Drury enjoys getting behind the headlines and takes every opportunity to set the record straight, as he sees it.

“People in England think Somalians are all gang members and drug dealers… not the people I know,” he says. “They are loving people who do their best and put their life on the line for you.”

Head down, eyes open

For destinations such as Syria, Drury crafts an itinerary with specialist operators that provide a local security detail.

He researches each location in advance and after arriving.

“If I’m going to Kirkuk [in Iraq], I’ll learn what road I’m taking there, what the village is like, what their allegiance is,” says Drury. “So if anything did happen to me, I would have some local knowledge.”

But from his experience, communities living with chaos often welcome tourists as a rare taste of normality, and chance meetings can lead to memorable experiences.

One such encounter was with a currency forger in Kandahar, Afghanistan.

“He was the worst forger ever,” recalls Drury. “He gave us a note that was wet and by the time we left it had no ink.”

Drury and his cousin gave the man an English banknote to test his skills on, and quickly discovered they shared a love of cricket. The forger would eventually guide them through an alternative tour of the city, including a secret smuggler’s bazaar.

In areas where a British hostage could be valuable, Drury has learned to bite his tongue.

“Don’t tell people where you’re going the next day, even if you trust them,” he advises. “If people want to meet again I say I’m catching a flight tomorrow.”

The Englishman has also learned to stay quiet through regular encounters with intelligence services – from U.S. “laundry men” in Kurdistan to a hidden floor in a Pyongyang hotel.

Despite the constant danger, Drury says he no longer fears violence.

“Now it’s more fear of not being frightened. I should be – fear keeps you alert.”

Pushing the boundaries

Several of Drury’s trips have been arranged through Untamed Borders, an operator with a record of notable firsts – the first to offer skiing vacations to Afghanistan, and the first British company to tour Chechnya.

Founder James Willcox rejects the “danger tourism” label, saying such trips offer a rich travel experience.

“We take people to places that are difficult to access and give them a variety of experiences – the geopolitical stories… the culture and history,” says Willcox.

“We try to see countries for the complex places they are and not a broad stereotype.”

The company draws on a global network of guides and security experts to enable vacations in danger zones.

Each trip requires months of planning, leaving nothing to chance.

Part of the planning stage is gaming worst-case scenarios.

“You have to look at where you’re going in a city if an attack happens,” says Willcox.

“You need to have a number of places to take guests.”

In emergencies, the company office becomes a control center to direct rescue operations, with staff gathering information for local partners or relevant authorities.

Ingle International specializes in insuring high-risk trips, with operatives on the ground in many danger zones. But a surge of inexperienced visitors to conflict zones is stretching capacity.

“We cover emergency evacuation – within limits,” says CEO Robin Ingle. “If [people] are in a war-torn area we may not be able to get them out.”

Requests for coverage in Iraq and Syria are increasingly popular, he says.

Some come from potential fighters – who are rejected.

New horizons

Trends in the wider travel industry suggest such vacation choices are becoming more common.

The adventure tourism market has exploded in recent years, with an estimated value of $265 billion.

Much of the growth is coming through wider access to “soft” adventures such as cycle tours and safaris, says Shannon Stowell, president of the Adventure Travel Trade Association, but there’s also more interest in hostile environments.

“All the buzz is for destinations that have some sort of edge,” says Stowell.

“Myanmar, Cuba and even North Korea are starting to pop up on radars,” says Stowell. “There’s intrigue – people wonder what’s behind the wall – and a feeling of danger.”

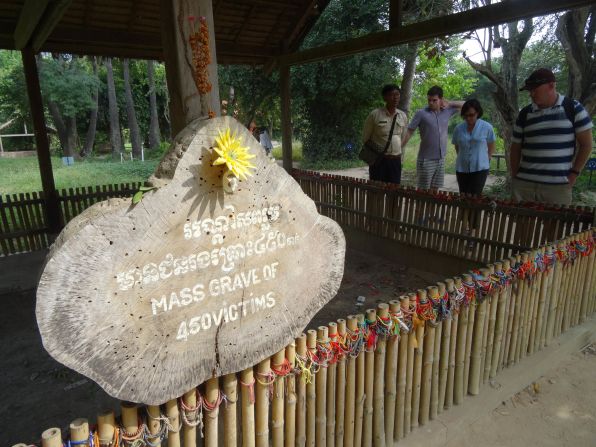

There’s also growing fascination with death and disaster sites.

Chernobyl and Auschwitz are seeing record visitor numbers and the Killing Fields are one of Cambodia’s leading attractions.

Death draws a crowd

Visitors to such sites are often looking for understanding, believes Dr. Philip Stone, head of the Institute for Dark Tourism Research.

“Dark tourism suggests a morbid fascination with death, but it’s more about living and connecting with our world, politics and heritage,” says Stone.

“In a secular society… the Internet and tourism can provide meaning.”

Death has always drawn crowds since the gladiators of Rome, says Stone, but increased interest has raised moral questions.

He’d like to restrain the entrepreneurial tendencies that made instant attractions of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and the crash site of United Airlines Flight 93, and ensure such sites carry a strong message.

“There is often a fine line between commercialization and memorialization,” he says.

“The tourism industry must look at the messages presented at these places – the history, heritage, politics – and what visitors are taking away with them.”

If managed respectfully, Stone believes that disaster sites can broaden the mind in the best traditions of travel.

Few tourists are ready to book their vacation in Iraq just yet.

But as more travelers demand experiences with a sharper edge than all-inclusive vacations can provide, the world’s darkest corners are opening for business.