360° Video: Step inside the abandoned city of Pripyat, Ukraine decades after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster left it uninhabitable.

It’s the site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster, responsible for causing an incalculable number of deaths and exposing millions to dangerous radiation.

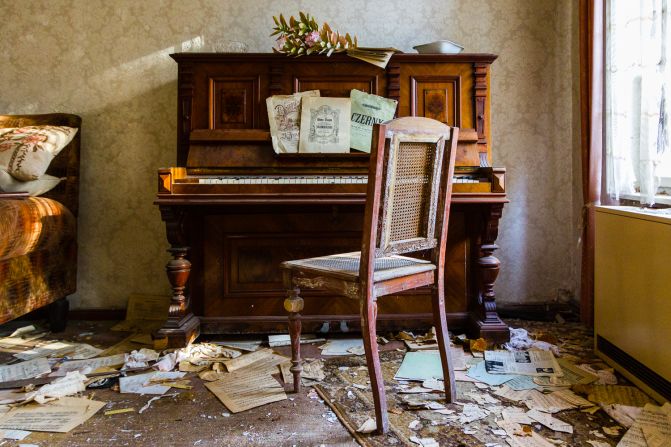

It’s also a tourism hotspot, a place where visitors seemingly strip off for selfies in front of abandoned buildings and snap artistically macabre shots of ruined relics.

This is Chernobyl, which in 1986 became the scene of the world’s worst nuclear disaster when a reactor explosion pumped out radioactive contamination over a huge area, causing widespread human suffering and prompting an entire region to be evacuated.

Today, groups of tourists throng through the abandoned city of Pripyat, next to Chernobyl, to experience deserted nurseries, funfairs, stores and other grim spectacles of the site – their bleeping radiation monitors adding an eerie soundtrack.

Chernobyl is one of the most popular examples of the phenomenon known as dark tourism – a term for visiting sites associated with death and suffering, such as Nazi concentration camps in Europe or the 9/11 Memorial and Museum in New York.

“It’s […] living on the edge almost – if you go to a place where people have really died,” Karel Werdler, a senior lecturer in history at InHolland University in the Netherlands, tells CNN Travel. “It also confronts you with your own mortality.”

Visiting such locations can be an edifying experience, driving home the horrors that humankind or nature is capable of. But the morals and pitfalls of dark tourism, and what constitutes acceptable behavior in such places, are becoming murkier in the social media age.

On the rise?

Chernobyl and Pripyat have been on the dark tourism map since the radioactive Exclusion Zone surrounding them opened up to visitors in 2011, but – prompted in part by the launch of popular HBO mini series “Chernobyl” – travel interest in the Ukrainian site has grown considerably in recent weeks, according to tour operators.

“After the show, I started to watch a lot of documentaries to find out more about what happened in Chernobyl, and I found out there are tours and you can come over,” one recent visitor, Edgars Boitmanis, from Latvia, tells CNN.

Chernobyl isn’t the only site of suffering that’s topping “must-visit” lists. Some 2.15 million people visited Auschwitz-Birkenau camp in Poland in 2018, roughly 50,000 more than the previous year. That’s a relatively small increase in numbers, but seems to reflect a global trend.

As international tourism skyrockets – in 2018, there were 1.4 billion international tourist arrivals – interest in dark tourism is also escalating.

“We’ve got two things at play here,” says Philip Stone, executive director at the Institute for Dark Tourism Research at the UK’s Lancaster University.

“We’ve got dark tourism, which has always been around in different guises. And then you’ve got the issue of overtourism, where popular sites are becoming even more popular. And then you’ve got the mass movement of people – so it’s almost kind of a perfect storm.”

Stone tells CNN Travel that, while it’s impossible to quantify whether dark tourism specifically is growing, because it’s too tricky to define the phenomenon, there is growing interest in the concept both academically and in the media.

Defining dark tourism

A photo tour of the abandoned Chernobyl site

Dark tourism as a term was coined in the 1990s, by scholars exploring why tourists visited sites associated with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The concept’s also sometimes called thanatourism, – from the Greek word thanatos, meaning death, or grief tourism.

But visitors were traveling to sites associated with death and destruction way before the ’90s.

Pompeii, the Roman city destroyed by a volcano eruption in AD79, has been on the tourist trail since the 1700s, and is still one of Italy’s most-visited destinations.

“It’s not as new as it may seem,” says Peter Hohenhaus, who chronicles his experiences visiting dark tourism sites on his website, Dark-Tourism.com.

Tony Johnston, head of Tourism at Althone Institute of Technology in Ireland, says motivations for visiting these places vary from individual to individual, and from site to site.

Some visitors are there just because they’re on vacation in the area, others pursue a historical passion. There are also thrill seekers going for “fun,” says Johnston – and a small group might have a morbid interest.

Most tourists behave respectfully, he clarifies.

“Quite often the intention of the visitor is to learn about atrocity or a dark heritage in a useful way, and it could be a reflection on what went wrong in the past and what lessons they can learn from the future so that mistakes aren’t repeated again,” says Johnston.

Stone, of the Institute for Dark Tourism Research, goes as far as to say there’s “no such thing as dark tourists.”

“People who are either on vacation or on study trips […] that doesn’t make us ‘dark’, that just makes us interested in what’s happening at these particular sites and learning from them,” he says.

But, says Rebekah Stewart, communications and outreach manager at the Center for Responsible Travel, a Washington D.C.-based research organization, motivations do matter.

“Before visiting places that are associated with death and tragedy, it’s important to reflect upon your intention,” she tells CNN Travel. “Are you visiting to deepen your understanding and pay your respects, or are you going to check a box or take a selfie?”

Inappropriate behavior

Haunting photographs of Pripyat

Recent months have seen some keen to define what is appropriate behavior at such sites.

In March, the Auschwitz Memorial Museum tweeted images of visitors posing on the train tracks outside the camp and wrote: “Remember you are at the site where over 1 million people were killed.”

In June, Twitter user Bruno Zupan shared four photographs of people purportedly visiting Chernobyl. One in particular, showing a woman in a hazmat suit unzipped to expose her underwear, sparked outrage.

Some of the people whose Chernobyl photographs were shared have since spoken to outlets including the i, saying they aren’t influencers, arguing that the context of the photographs has been lost or even that they weren’t actually in Chernobyl at all.

Still, the viral images sparked a widespread debate on what kinds of photographs – if any – are appropriate at dark tourism sites.

Photographer Nigel Walshe, who visited Chernobyl a few years ago and took a series of evocative images in Pripyat, including photographs of an abandoned high school, says he largely avoided images that featured people.

“I also reject the common, but highly intrusive way in which people are often included in pictures of ‘dark’ scenes, almost as props, to add some ‘human interest,’” he says.

Abandoned Berlin: Inside the city's forgotten places

Ciarán Fahey, another photographer whose striking images of abandoned sites in Berlin, including one location used for Nazi experiments on prisoners, were spotlighted by CNN in 2017, agrees with Walshe.

“I think respect is simply showing what you find, not bringing adornments, props or anything else. I don’t think a fashion shoot in a place where Nazis tortured victims is appropriate or respectful, for example,” he says.

For some, any photograph is disrespectful, but selfies are particularly bad.

Some of the eeriest locations on the planet

“It’s more than pure narcissism,” Darmon Richter, a photographer whose doctorate studies focus on dark tourism, tells CNN. He says the way people communicate now is different.

“More and more people are very visually oriented orientated in the way they communicate with their peers.”

Taking photographs, says Stone, is part of how modern day tourists document their travels – the equivalent of writing “I was here” on a wall, however the egotistical appearance of selfies “doesn’t sit well with these sites of conscience.”

Ethical consequences

It’s not just visitors who need to consider their treatment of sites of tragedy, the experts say.

Werdler, of InHolland University, points out that most tourist attractions need parking spots, bathrooms and food outlets.

“You have to be also thinking about the ethical consequences of entertaining your visitors,” he says. “But where do you draw the line?

“I think it is very inappropriate to sit in a restaurant in Auschwitz and eat during my lunch break. But other people have less constraints with that.”

The passage of time is also a factor to consider. Pompeii, for example, may feel like a more “acceptable” dark tourism site, because the disaster occurred so long ago.

“Memory is critical,” says Johnston. “We will act a certain way around the gladiator outside the Colosseum in Rome, we might stand and pose for a photograph. But this is somebody who represents someone who was employed to quite brutally kill people, but because it was 2000 years ago, and it’s distant in the past, it seems temporally acceptable.”

Some sites actively try to resist dark tourism.

In Japan, in Fukushima Prefecture – the site of a 2011 fatal earthquake, devastating tsunami and nuclear disaster – authorities have made a conscious move away from promoting disaster tourism, instead marketing the region as a safe, interesting place to visit.

As part of that, Jun Muto, head of the tourism department in Fukushima Prefecture Tourism and Local Products Association, tells CNN Travel they’re focusing on “hope tourism.”

Muto and his team want visitors to see “the Fukushima that is recovering after the nuclear disaster, but also make sure to see the side of Fukushima full of rich history, nature, and many fantastic sightseeing spots.”

Personal stories

See the renovated Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima

So where’s the line between a thought-provoking, educational excursion and macabre, misplaced voyeurism?

For some museums and memorials, the key is to concentrate on the human stories behind the mass tragedy, re-centering the victims to the heart of the narrative.

At Japan’s newly reopened Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, an extensive two-year renovation lead to an increased emphasis on personal artifacts and survivor’s stories.

The 9/11 Memorial & Museum features portrait photographs of the people who were killed on September 11, 2001 and the February 26, 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center. Audio recollections from loved ones are accompanied by victims’ personal artifacts.

For many visitors to Auschwitz and the other European concentration camps, hearing the victims’ stories, and seeing the belongings that were taken from them, is the most impactful and moving part of the visit.

Broadening horizons

Johnston recommends visitors educate themselves prior to their trip, to “really learn about the history of the site, the people that were there, the human stories of the tragedy that unfolded,” he says.

Other experts, including Stone, suggest extensive research isn’t integral, as long as you go in ready to learn what happened, and respectful of the significance of the site.

In Chernobyl, despite the recent controversies, visitors who spoke to CNN seemed mindful of the horrors that had befallen the location and the lessons on offer.

Among them, Joe Robinson, from Hull in England, said he was risking mild exposure to radiation and exploring the Exclusion Zone around the nuclear reactor to take stock of a situation caused, in part, by catastrophic political decision making.

“There’s a consequence of the lies,” he says. “You can watch the news and think nothing, but Chernobyl shows how far people would go to protect their reputation.”

Dark-Tourism.com editor Hohenhaus thinks this applies to many dark tourism spots.

“If you’ve encountered and dealt with sites that are very much propaganda-lead – like Nazi sites, Communism sites, and so on – then you can see through propaganda better, you recognize it. So it also gives you an advantage outside the tourism sphere.”

The key, most experts agree, is to visit responsibly and respectfully.

CNN’s Matthew Chance and Zahra Ullah contributed to this story

![<strong>Radioactivity detection:</strong> "It's absolutely safe," Korol says of safety concerns regarding radiation levels. "The radiation they [visitors] are exposed to on a tour is less than on an intercontinental flight."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/190610111659-chernobyl-tourism-geiger-counter-getty-images.jpg?q=w_1600,h_900,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)