China is making it easier for foreigners to enter the country. But there’s one condition: they need to have received a China-made Covid-19 vaccine.

At least 23 Chinese embassies around the world issued new visa policies over the past week with this condition, including in the United States and United Kingdom – both places where Chinese vaccines aren’t available.

China’s foreign ministry says the move is about kick-starting international travel in an “orderly fashion,” and vaccinated travelers will still face state-run quarantine on arrival.

But experts have raised concerns over China’s decision to prioritize domestic vaccines over those approved by the World Health Organization, and with a higher efficacy rate.

They say it risks pressuring countries to approve Chinese vaccines and sets a dangerous precedent which, if adopted by other nations, could leave the world in vaccine-based silos.

It also raises practical issues – what options do people have if they live in countries which haven’t approved China-made vaccines?

“It’s very much at the sharp end of vaccine diplomacy,” said Nicholas Thomas, an associate professor in health security at the City University of Hong Kong. “(It’s) essentially saying if you want to visit us, you need to take our vaccine.”

What’s behind the move?

The timing of China’s new visa rules is notable.

After the Quad – a partnership between the US, India, Japan and Australia – met last week, US President Joe Biden announced they would together finance, manufacture and distribute at least 1 billion vaccines for the Indo-Pacific by the end of 2022.

Those vaccines would be developed in the US and manufactured in India, which has been engaging in its own vaccine diplomacy around the region. Some saw that as a direct counter to China’s own vaccine diplomacy efforts, which were recently criticized by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, saying Chinese vaccines comes with “strings attached.”

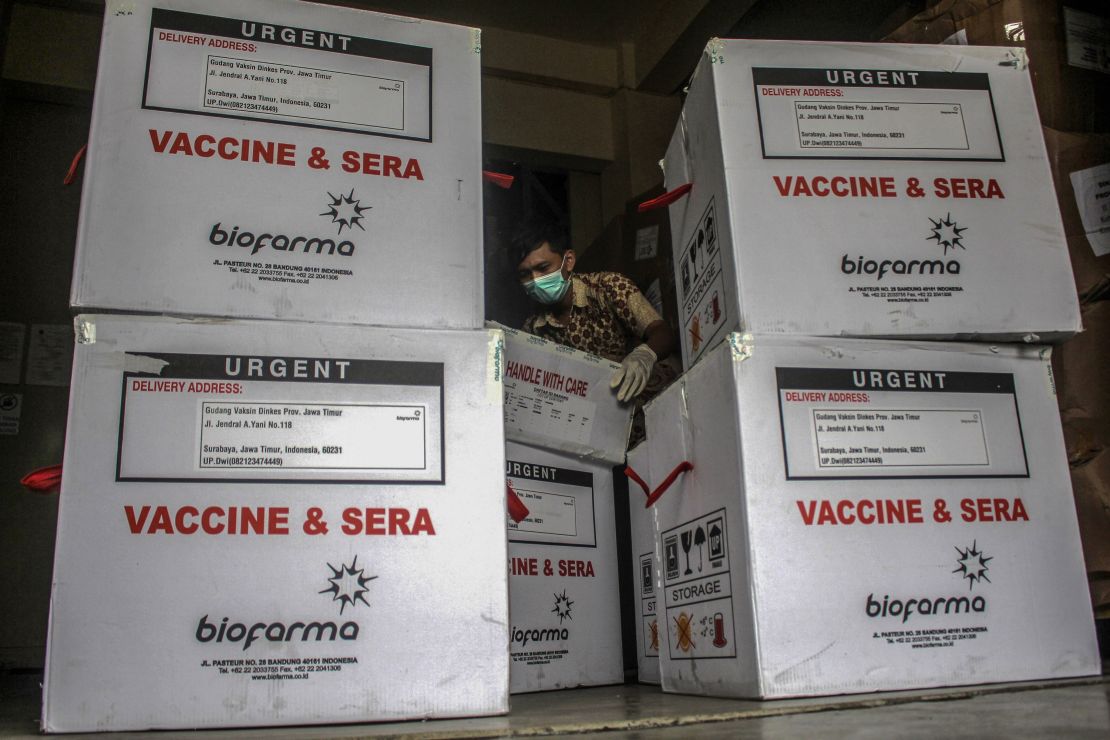

China has been one of a number of countries at the forefront of vaccine development and, as of March 15, China had exported vaccines to 28 countries, according to the Chinese Mission to the UN. Mass public vaccination programs with Chinese vaccines are underway in Indonesia and Turkey. In China alone, 65 million people have been vaccinated with the country’s five approved domestically produced vaccines.

But none of China’s vaccines have yet been approved by the WHO or have released full Phase 3 trial data, leading to a lack of clarity over how effective the vaccines really are. The available data suggests China’s vaccines may actually be less effective than other vaccines – Sinovac, for example, had an efficacy rate of 50.38% in late-stage trials in Brazil, lower than the 78% announced in China, and lower than the efficacy rate of other vaccines such as Pfizer, which has reported a 95% efficacy rate.

That means China can’t claim its preference for homegrown vaccines is due to them being superior to other vaccines. Instead, Thomas sees China’s new visa rules as a “power move,” which will pressure people to take one of China’s vaccines.

Sarah Chan, a reader in bioethics at the University of Edinburgh’s College of Medicine, says if someone’s livelihood depends on traveling to China for work, that could push them to take the vaccines, despite their lack of data. Scott Rosenstein, director of the global health programme at Eurasia Group, said it could also pressure countries to authorize the Chinese vaccines.

Some people may have health conditions that mean they are unable to take certain shots. “It is simply not justified to make so much of what we do depend on whether or not we have had a vaccine, let alone whether we have had one particular version of the vaccine,” Chan said.

Despite China’s new visa rules placing an incentive on travelers to take the Chinese vaccines, Zhao Lijian, spokesperson of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, rejected the idea of “vaccine nationalism.”

“Regardless of where a vaccine is made, it is a good vaccine so long as it is safe and effective,” he said in a press conference Monday. “China stands ready to advance mutual recognition of vaccination with other countries.”

What are the longer term effects?

China’s move comes as countries around the world tackle the broader question of whether to roll out so-called “immunity passports” to open up international travel to people who have antibodies to coronavirus – either because they have recovered from it or through a vaccine.

But that leads to more questions – if an immunity passport gives special rights to people who have been vaccinated, which vaccines should be counted?

One option is to follow the WHO authorization. Currently, only four vaccines, including two versions of the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine, have been given emergency use listing by the WHO – and none are China-made.

Another option is to let the 194 member states of the World Health Organization vote – those vaccines approved and recognized by the most countries would set the standard, according to Thomas.

But a uniform vaccine passport for the world is a long way off. For now, countries are likely to simply recognize the vaccines they have approved for use – and already there’s signs of that leading to silos.

The European Commission this week announced a Digital Green Certificate with a QR code to show whether a person has been vaccinated. But member states will only waive free movement restrictions for people vaccinated with shots that have received EU marketing authorization – those who’ve had the Chinese shots may be left in the cold.

“It is this brewing tit-for-tat challenge that I think will be interesting to watch,” Rosenstein said. “It will create a certain amount of tension and will escalate this pre-existing vaccine diplomacy tension.”

Rosenstein said people might even opt to take multiple vaccines so they can travel to other regions – a step unlikely to have negative health effects, but which could stress vaccine supply.

What’s the best way forward?

Even aside from the problems of deciding which vaccines are accepted, there are other issues with immunity passports – we don’t know how long immunity to Covid-19 lasts, either from recovering from the virus or from vaccines. There are also ethical issues – while the WHO is working on a “smart digital certificate” that would include vaccination information, it is discouraging the use of vaccine passports for travel. “There is a global shortage of vaccines,” WHO Europe director Hans Kluge said Thursday. “So this would increase the inequities.”

Chan sees a raft of problems with immunity passports, especially high-tech digital ones that come with data privacy concerns. She also points out that once everyone has had a chance to be vaccinated, vaccine passports could become obsolete quickly – meaning money could be spent better elsewhere.

A better approach would be making sure vaccines are as widely available as possible, she said. Then, when much of the world’s population has been vaccinated, immigration authorities can use simpler approaches, like asking the public to self-report if they’ve had any vaccine. If some people lied, the risk to the population overall would still be small, as most people had been vaccinated, she added.

Thomas also hopes for a best-case scenario where countries don’t follow China’s lead – instead, they treat all vaccinated people the same, regardless of the vaccine, so long as the vaccine has data to support its efficacy. He hopes countries can stop treating the vaccine rollout as a race, and instead treat it as a global health issue.

“The viruses don’t care about borders, they don’t care about nationalities or races or religions or ideologies or ethnicities or anything like that, they just want to replicate and mutate,” he said.

“And I think unless we do take a truly global approach to vaccines, and recognize that we have to simply do the best on a global level, then we’re going to be looking at latent pools of Covid cropping up again in the future and possibly like the second wave of the Spanish influenza, mutating in such a way that makes it worse than before.”