Pulling out from beneath St Pancras’s magnificent wrought iron roof, the Eurostar slipping through tunnels towards the Kent countryside, it’s easy to feel blasé about taking a train from London to mainland Europe.

From the ease of checking in at the UK’s finest rail station just 30 minutes before departure to arriving in the heart of Paris, Brussels or Amsterdam without having to deal with baggage reclaim, traveling by rail to northern Europe feels both seamless and everyday.

Likewise, driving onto a dedicated train Eurotunnel Le Shuttle service near Folkestone for a 35-minute ride to Calais, far quicker than using a ferry across the English Channel, is now seen as completely normal.

The same can be said for freight train drivers readying themselves for an epic 18 day, 7,500-mile trip from Barking in East London all the way to China.

The feat of engineering that has made this all possible, the Channel Tunnel, opened 25 years ago. Queen Elizabeth II and then French President Francois Mitterand officially cut the ribbon at special services in Folkestone and Calais on 6 May 1994, with Eurostar services running to Paris from London from November 1994.

In the quarter century since, it’s become not only a vital physical link between the UK and mainland Europe, but a highly symbolic one, particularly in an era of Brexit.

“It put international rail travel back in the game,” says Mark Smith, founder of rail travel website The Man in Seat 61.

“It changed the perception of Brussels and Paris from being destinations you needed to go to via an airport, such as Vietnam and Australia, into places that are just down the road, like Manchester or Leeds.”

Some 4.5 million UK tourists use the Channel Tunnel every year, with 1.6 million trucks transporting goods between the UK and the continent, making it worth around €140 billion per year to the UK and European economies, according to EY’s Economic Footprint of the Channel Tunnel in the UK report from 2018.

Fears of invasion

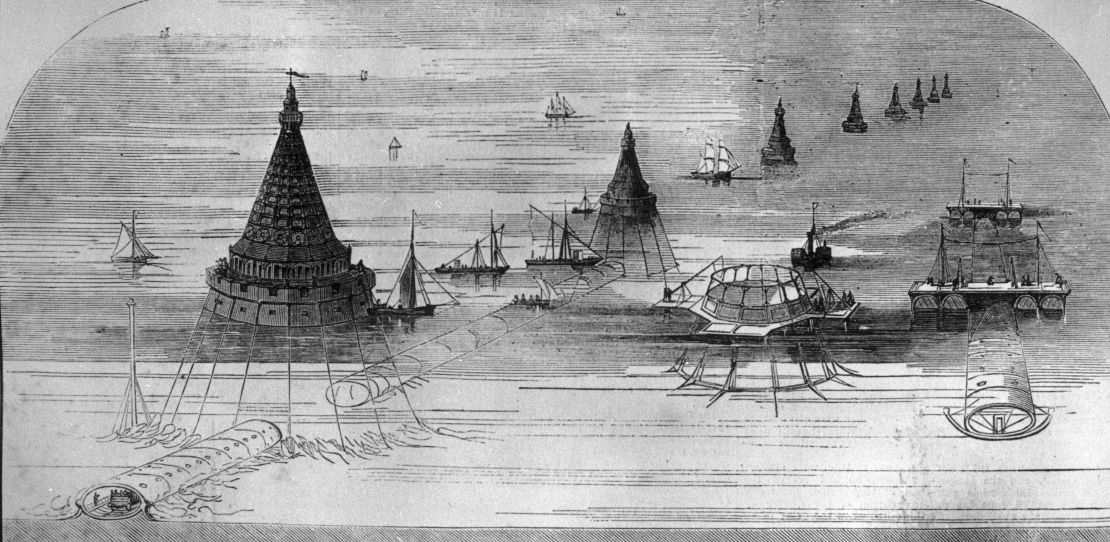

The tunnel itself had been mooted for over 180 years before British and French workers broke ground and began digging towards each other in 1988. French engineer Albert Mathieu-Flavier first proposed a subterranean link between Britain and France in 1802, suggesting the creation of an artificial island in the English Channel for trains to change the horses that would be required to pull the carriages.

The concept continued to rear its head throughout the 19th century, with engineers even digging tunnels into the bedrock before plans were abandoned in 1882, with British politicians fearing that the tunnel would compromise the country’s defenses.

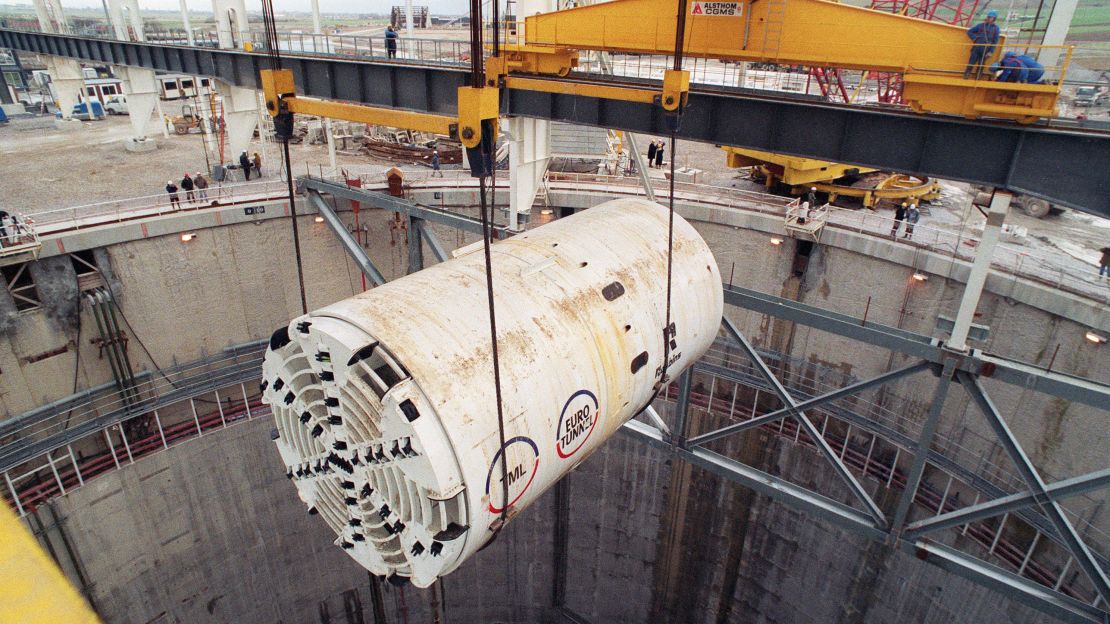

It wasn’t until 1987, after numerous false starts following World War II, that the British and French parliaments agreed to the project, with two rail tunnels and a third service tunnel preferred to plans for road tunnels and a suspension bridge.

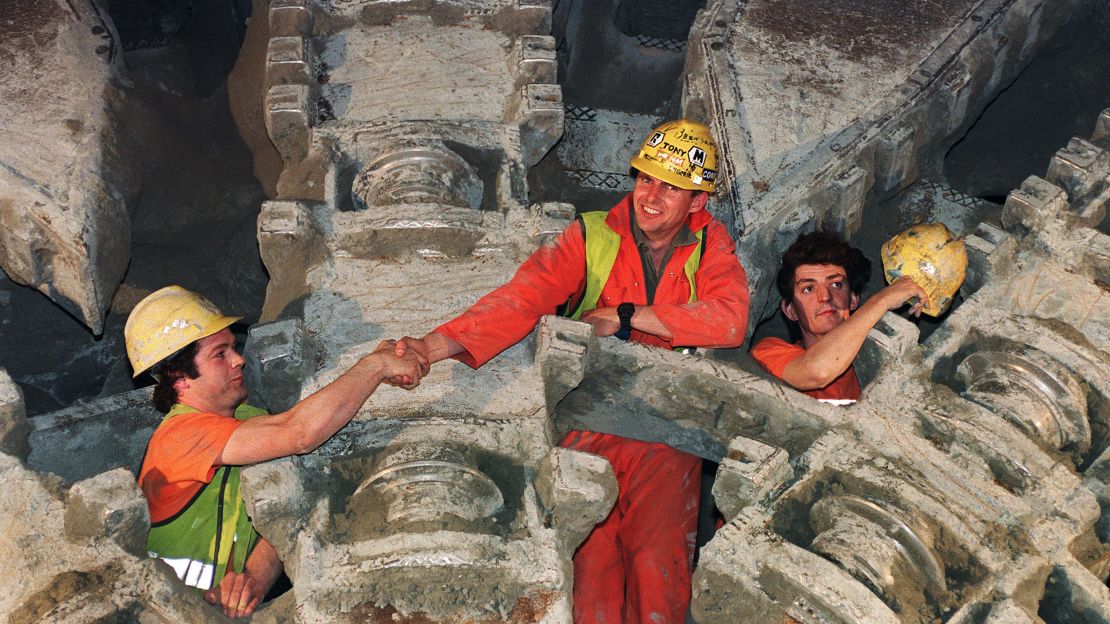

It took six years for 13,000 workers to build the 31.4 mile tunnel, 23.5 miles of which run undersea, making it the longest of its kind in the world. Inevitably, that kind of engineering and manpower did not come cheap, with costs in 1994 estimated at £4.65 billion (about $7.2 billion), a massive 80% more than originally planned.

There was so much spoil left over from the tunnel that an entire nature reserve, Samphire Hoe, was created on the UK side. Consisting of 4.9 million cubic meters of chalk, it overlooks Dover’s famous White Cliffs.

On opening, the Channel Tunnel was dubbed one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World by the American Society of Civil Engineers, alongside the Empire State Building and Toronto’s CN Tower.

Despite the eye-watering cost, the tunnel became an immediate hit with travelers. “It played its part in changing public attitudes towards railways, which for many years had been declining in importance, and helped spark a railway renaissance across the UK,” says Ed Bartholomew, lead curator at the UK’s National Railway Museum in York.

Mark Smith agrees, saying the ongoing popularity of taking the train from the UK to Europe speaks to a wider grassroots distaste with flying.

“Mainstream travelers now come to my site,” he says. “When they tell me why they’re going by rail rather than air, they say two things in the same breath: They’re fed up to the back teeth of the airline experience and they want to cut their carbon footprint. It’s like those two are flip sides of the same coin.”

A journey from London to Paris emits 90% less greenhouse gas emissions than the equivalent short–haul flight, according to Eurostar.

“From the early days of operation, Eurostar has championed the environmental benefits of high-speed rail and encouraged the switch to sustainable modes of transport for short-haul international travel,” a Eurostar spokesperson told CNN.

A slow start

The initial experience, however, was much removed from the high-speed delights experienced by today’s travelers. While the French side of the tunnel utilized high speed lines into Paris from the get go, traveling in and out of London was a lot more sedate. For a start, services ran from Waterloo, just south of the Thames, rather than the current terminal at St Pancras.

And while facilities at the station itself were good, trains had to travel on commuter lines through the south of the city thanks to legal assurances made by the UK government in 1987 that no public money would be used for a high-speed rail link to the tunnel.

“Britain had to make use of existing lines running through one of the most intensively worked and congested commuter systems in the world,” says Ed Bartholomew. “That meant that for the first 13 years of operation, passenger trains ran into Waterloo station on a DC electric system and, almost comically, Eurostar trains capable of 300 kph (186 mph) had to pass over a manually operated level crossing gate just south of Ashford station.”

The experience was, frankly, embarrassing. The planned journey time of two hours and 50 minutes would lengthen when trains got stuck behind stopping services, throwing into sharp relief the difference between rail infrastructure in the UK and mainland Europe.

“The French approach to financing, government management and planning was very different and demonstrated a much bolder attitude to grands projets,” adds Bartholomew.

Mercifully, the development of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, also known as High Speed 1, meant an end to chugging through London’s leafy southern suburbs. The £11 billion route was beset by political and funding difficulties, but the first section, running 46 miles from the tunnel to a junction in northern Kent, opened in September 2003, followed by the final 24.5 mile section into London in November 2007.

With its completion, Eurostar services moved from Waterloo to the newly redeveloped St Pancras, with journey times to Paris down to as little as two hours and 15 minutes.

The updated station, already one of London’s greatest Victorian buildings, has become a byword for the laid back approach of continental train travel compared with the harried experience found at airports.

It stands in stark contrast to the dingy, outdated Gare du Nord in Paris, where check in and passenger facilities remain underwhelming at best and cramped and uncomfortable at worst.

There was also another important aspect of making the switch to St Pancras: the trains themselves.

“Traveling on a high-speed railway line for the whole journey enabled the purchase of new state-of-the art trains with more capacity, onboard entertainment and Wi-Fi,” Eurostar tells CNN.

Today’s trains are noticeably more modern than the original rolling stock, where a lack of internet connection proved an issue with business customers zipping between London and mainland Europe.

Expanding horizons

While initial Eurostar services ran through the Channel Tunnel to Paris and Brussels, newer destinations have been added in recent years. Seasonal routes take in the south of France in the summer and the French Alps in winter have become hugely popular, as has the ability to book through to over 100 destinations in Europe and the UK, meaning it’s possible to use the Channel Tunnel to plug into the wider rail network.

In April 2018, Eurostar opened a new direct route to Amsterdam, with a journey time of three hours and 55 minutes. However, passengers coming back need to take a train to Brussels to connect to a Eurostar service back to London. Despite that kink, over 250,000 people have used the service in the past year, with demand seeing a third daily train added. Pleasingly, the indirect return trip also looks set to be a thing of the past very soon.

“The governments have committed to finalizing an agreement to allow us to run a direct return journey by the end of the year,” said Eurostar. “When we have this we’re sure that it will feed the growing appetite among customers for high-speed, sustainable rail travel.”

That said, plans for services to Frankfurt via Cologne, run by the German national rail operator Deutsche Bahn (DB), were shelved in June 2018 citing changes in the “economic environment,” suggesting any newer routes are unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Brexit, with its new deadline of October 31, may also have had a part to play in DB’s decision. Eurostar told CNN it planned to maintain its existing services even in the event of no deal being agreed between the UK and EU.

A success story?

From a travelers’ perspective, it’s hard to resist the allure and romance of the Channel Tunnel, an engineering project dreamed up over 200 years ago and now the most pleasant way to travel between the UK and Europe.

“The Channel Tunnel is a political, diplomatic, financial and technical success,” says Ed Bartholomew. “It’s now firmly embedded in the economies of Britain, Ireland and continental Europe.”

Mark Smith agrees. “It certainly fulfilled the promise for London to Paris and Brussels. It’s now normal to go there by train and odd if you go there by plane. But there’s lots of capacity left: The freight hasn’t fulfilled its potential and there’s still capacity for passenger trains.”

There have been a string of events that have seen the Channel Tunnel in the headlines for the wrong reasons since its opening, from 1,000 passengers being trapped underground overnight on Eurostar trains in February 1996 due to electronic failures to fires and union action bringing services to a halt.

Throughout its life, the tunnel has proved irresistible to migrants from Africa, the Middle East and beyond who have tried to use it as a way to across the Channel illegally into the UK. Eurotunnel claimed more than 20,000 security breaches involving migrants in 2016.

Such incidents have left enthusiasm for the tunnel undimmed.

In an age when concerns about the environmental cost of air travel are growing, the Channel Tunnel, for all its teething problems, has become a beacon for what is possible when infrastructure projects are given the go ahead.

And while its green credentials will ensure it remains every bit as popular for the next 25 years, it’s also impossible to deny the pleasures of sipping on a glass of Burgundy as the Eurostar zooms out into the French countryside and on towards some of the world’s most beguiling cities.