Once upon a time, the locals peddled rice on Bangkok’s Khao San Road. Lots of it.

Barge after barge paddled, and later motored, down the vast Chao Phraya River and into the mouth of Banglamphu Canal, where they dropped off thousands of tons in jute sacks to wholesalers in the neighborhood.

By the end of the 19th century, Banglamphu district was by far the largest rice market not only in Bangkok, but anywhere in Siam, the world’s largest rice growing nation.

Smaller vendors opened shops south of the canal, where a dirt-track alley became so thick with the rice trade that King Chulalongkorn ordered a proper road built in 1892. Running only 410 meters, the cobbled strip wasn’t grand enough to be named after a historic Thai figure or nation-building principle, unlike other city thoroughfares, so it was simply called Soi Khao San (Milled Rice Lane).

As Banglamphu flourished on rice profits, the district expanded into clothing (including Thailand’s first ready-made school uniforms), buffalo-leather shoes, jewelry, gold leaf and costumes and regalia for Thai classical dance theater. Local demand for entertainment gave birth to two musical comedy houses, Thailand’s first national record label (Kratai), and one of the kingdom’s first silent-movie cinemas.

Yet only 100 years later, an invasion of international backpackers almost completely eclipsed local market culture. Starting as a trickle in the late 1970s, when Bangkok was a terminus for the Asian hippie trail, the influx became a tidal wave in the 1990s.

Guesthouses proliferate

I don’t think anyone could have predicted the inexorable evolution of the road and surrounding neighborhood.

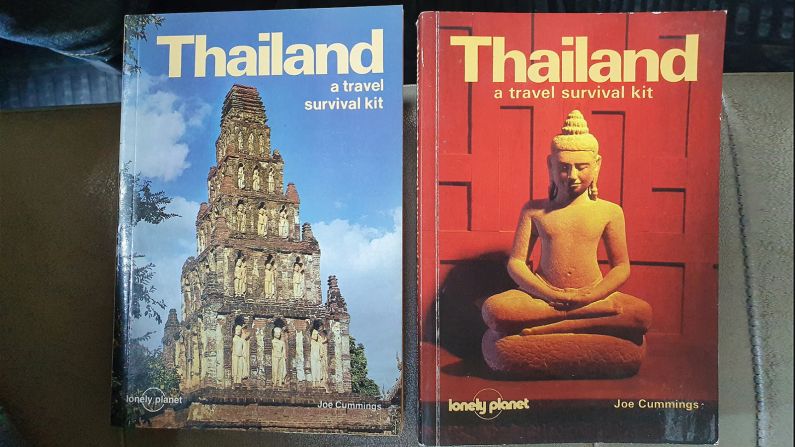

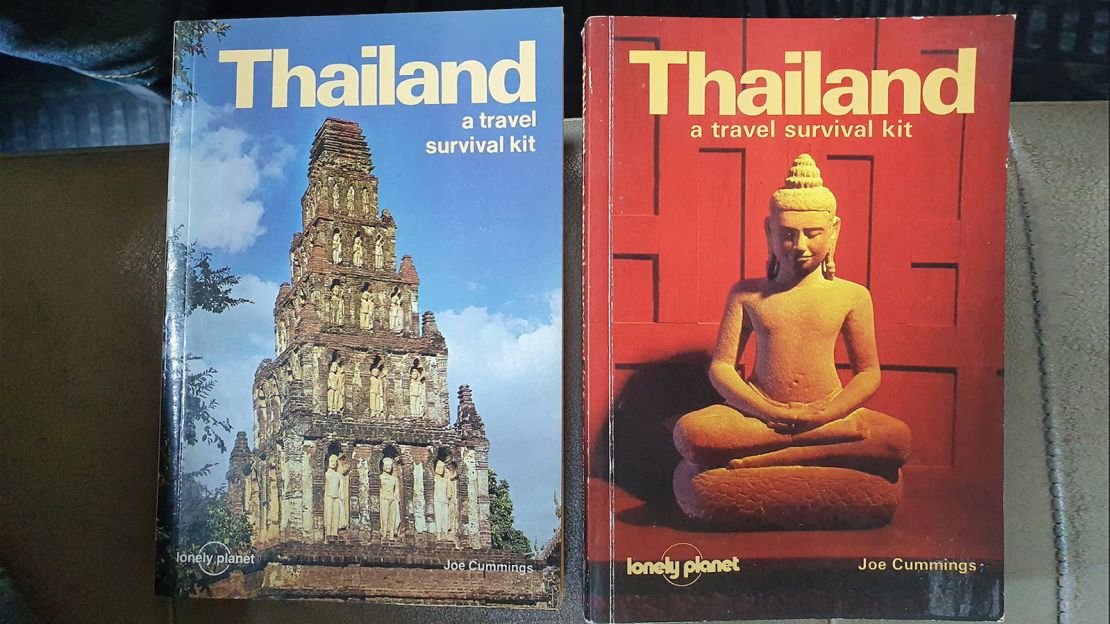

When I first strolled down Khao San Road on a research trip for the first edition of Lonely Planet’s Thailand guide, 40 years ago, it was lined with late 19th- and early 20th-century two-story shophouses.

At street level were rows of shoe shops, Thai-Chinese coffee shops, noodle vendors, grocers and motorcycle repair shops. Owners or tenants lived above.

A few rice dealers hung on, but as 10-wheel trucks had taken over from river barges, rice transport and trading had for the most part moved elsewhere.

While Yaowarat, Bangkok’s Chinatown, was the main commercial focus for Chinese merchants and residents, and Phahurat served the Indian community, Banglamphu was clearly a more Thai realm. Around the corner on Chakkaphong and Phra Sumen roads, artisan shops still crafted costumes and masks for classical Thai dance-drama performers.

I had a spent a long, hot day jotting down notes on the Grand Palace, the Temple of the Emerald Buddha (Wat Phra Kaew), the Temple of the Reclining Buddha (Wat Pho), and the Giant Swing, all of which lie within a kilometer’s radius of Khao San Road.

These are arguably the city’s chief sightseeing attractions, so when I noticed two Chinese-Thai hotels on Khao San Road, I immediately thought to recommend them in my guidebook as a convenient base for travelers. Nearly identical in their modest amenities, Nith Chareon Suk Hotel and Sri Phranakhon Hotel cost $5 a night at the time, and catered to Thai traders buying wholesale goods in Banglamphu to sell upcountry.

Down a narrow alley nearby, I was even more thrilled to stumble upon VS Guest House, recently opened by a Banglamphu family taking guests into their 1920s-vintage wooden house for $1.50 per head. Further alley exploration turned up two more family-run, similarly priced guesthouses, Bonny and Tum.

These two hotels and three guesthouses formed the sum of Khao San Road accommodations I listed in the first “Thailand: A Travel Survival Kit,” published the following year, 1982.

When I returned a year later to update info for the second edition, five more guesthouses along or just off Khao San had appeared, so I dutifully added these for the 1984 edition.

From that point forward, every time I came back to Banglamphu for the guide’s biannual update, the number of places to stay had multiplied exponentially. Within a decade, the choices proliferated, block by block, from Khao San Road out to other streets and alleys in the district, until backpacker hotels and guesthouses numbered well over 200.

“The Beach” effect

By the mid-1990s, the neighborhood was a global phenom, the largest backpacker center among the three Ks – Kathmandu, Khao San, and Kuta Beach. Besides housing and feeding the largest transient backpacker population in the world, Khao San Road became a world-record contender for its black market in unlicensed cassettes, CDs and DVDs, fake IDs, counterfeited books and brand-knockoff luggage.

Dozens of bucket shops offered unrivaled bargain fares on little-known airlines flying imaginative routes to virtually any airport on the globe.

Alex Garland, an unknown writer at the time (now famed for directing sci-fi films “Ex Machina” and “Annihilation)’, boosted Khao San’s bad-boy rep further with his 1996 cult novel, “The Beach.” Based on Garland’s own travels in Thailand, the first seven chapters take place on Khao San Road, where Richard, a young English backpacker, meets an eccentric Scot calling himself Daffy Duck who gives him a secret map to “the beach.”

The novel describes a room in a typical Khao San guesthouse of the era: “One wall was concrete – the side of the building. The others were Formica and bare. They moved when I touched them. I had the feeling that if I leant against one it would fall over and maybe hit another, and all the walls of the neighboring rooms would collapse like dominoes. Just short of the ceiling, the walls stopped, and covering the space was a strip of metal mosquito netting.”

A film adaptation directed by Danny Boyle and starring Leonard DiCaprio hit world cinemas in 2000, and probably introduced Khao San Road to a larger audience than either the novel or my Lonely Planet guides.

That same year Italian electronic music producer Spiller released a video of his dance track “Groovejet (If This Ain’t Love),” shot in Bangkok with a prominent scene at the end where Spiller and singer Sophie Ellis-Baxter dance in an underground Khao San Road club.

A New Yorker article that year described Khao San Road as “the travel hub for half the world, a place that prospers on the desire to be someplace else,” because it was “the safest, easiest, most Westernized place from which to launch a trip through Asia.”

Khao San Road today

According to the Khao San Business Association, in 2018 the road saw an astounding 40,000-50,000 tourists per day in the high season, and 20,000 per day in the low season.

With such numbers, it wasn’t much of a surprise when the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority announced in 2019 that it was investing $1.6 million to transform Khao San Road into a regulated “international walking street.”

Initiated perhaps in part to counter Khao San’s somewhat unsavory reputation, the project was to be completed in late 2020, with a repaved road and footpaths, and retractable bollards designating spaces for 250–350 licensed Thai vendors, selected by lottery.

Vehicles would be banned from the road from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. daily.

When the coronavirus pandemic forced Thailand to close its borders in April 2020, international tourist arrivals fell to zero almost overnight. Khao San Road partially recovered when domestic travel re-opened in July, however, and by the time the renovated Khao San was launched in November 2020, weekends found the road packed with Thai youth as well as lesser numbers of expats.

Pubs along the street that typically boasted 80% European customers became almost 90% Thai.

A vibrant 10-day series of light installations called Khao San Hide and Seek attracted a steady crowd in November. The installations were supplemented by live performances from nearly 20 bands. Local studios led workshops focused on traditional Banglamphu arts such as embroidering khon (classic Thai dance-drama) costumes, preparing traditional khaotom nam woon (sticky rice triangles steamed in fragrant pandanus leaves), and crafting thaeng yuak (fresh banana tree trunks carved into intricate patterns, for use in funerals, monastic ordination and other Buddhist ceremonies).

The neighborhood suffered another setback when a second wave of coronavirus cases spiked in early January 2021. The government quickly ordered the closing of all entertainment venues in Bangkok, and once again Khao San Road emptied out almost completely.

When I re-visited a deserted Khao San later that month, I decided to stop in at VS Guesthouse, the first and oldest guesthouse still standing. Every other neighborhood guesthouse I passed by that day was shut tight, but to my surprise the vintage wooden doors to VS stood wide open.

I chatted with the members of the family who owned the house, now in their fourth generation. Rintipa Detkajon, the elder of two sisters who look after the home today, recalled how her late father, Vongsavat, started taking in foreigners around 1980, allowing them to sleep on the family’s living room floor.

“I was around 16 years old when our first guest, an Australian man, stayed the night,” she recounted. “Foreigners back then traveled so quietly. They were interested in history and culture, unlike youngsters we see nowadays, who seem more interested in getting drunk and partying.”

The family added to the wooden house over the years, at one point reaching a peak of 18 rooms. They now operate 10 rooms going for $10 a night. The day I visited, just one room was occupied, by an American who was staying long-term.

I asked Rintipa about the lack of business due to the pandemic.

“It’s not just us, it’s the whole world,” she said. “We’re all in this together. This is our home, so we’ll survive.”