It’s a discolored concrete slab, molding in the tropical humidity. But on this slab, not much bigger than the footprint of a beach cabin, history changed.

What was once a doorway is obvious, as are the bases for a couple interior walls and an opening for a larger garage-like entrance.

I walk through the doorway, through the interior and out the garage. As I do, my guide puts these few steps in extraordinary perspective.

“You’re walking the path of the atomic bomb.”

This slab is where the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki 75 years ago were put together. It’s the assembly point for the dawning of the atomic age.

Now it sits, essentially ignored, on the Pacific island of Tinian, from where the US Army Air Force B-29 bombers that performed those atomic strikes on Japan departed.

North Field

Tinian is part of the Northern Mariana Islands, now a US territory in the Pacific. In 2020, it’s a sleepy, rustic, tropical paradise of 3,000 residents. There are a handful of restaurants, a few small hotels and a single gas station on its 39 square miles (101 square kilometers).

In 1944, Tinian and its sister island of Saipan, five miles to the north, were the scene of brutal fighting between the United States and Japan.

Walking the path of the atomic bomb at Tinian's North Field

The US needed the islands so its state-of-the-art B-29 bombers could strike Japan, 1,500 miles away. And in the summer of 1944, after three months of combat that included some of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific, the US secured the islands and quickly built large air bases for its new bombers.

On a January morning 75 years later, I’m exploring one of those bases, North Field.

At the site of the atomic bomb assembly building, my guide and I hop into the rented Toyota Corolla for the next steps in the bombs’ journey, a short drive to pits into which they were lowered, then hoisted up into the bellies of the bombers that would carry them to their targets.

Tall grasses and brush have grown around North Field over the decades. They close in on the Toyota, even scraping its sides at some points.

But in 1945, this was an open plain filled with acres and acres of workshops and tents and airplanes and men, supporting what at one time during World War II was the busiest airport in the world.

While what surrounds us on this tropical morning has changed, what is underneath is the same asphalt laid by US Navy Seabees, or construction battalions, 75 years ago.

The longevity of that construction is in itself remarkable. Think of the roads and freeways you drive on, how potholes develop and surfaces crumble in within your short-term memory. The pavement below us hasn’t been touched in more than seven decades.

The path we’re driving emerges into a clearing about the size of a supermarket parking lot. Two glass structures, maybe four or five feet high, are visible at separate corners on the same side of the small pad.

My guide is Don Farrell, a California native who moved to the Pacific islands in the 1970s. Locals recognize him as the chief historian of Tinian, and he’s detailed the story of what happened here in 1945 in his book, “Tinian and the Bomb.”

He led the effort to get these bomb pits excavated and preserved more than a decade ago, and describes how the atomic bombs were loaded into the B-29s.

Think of when you’re getting your car serviced and a hydraulic lift brings it up above your head so the mechanics can work underneath. That’s how the bombs got into the belly of the planes, he says.

I back up the rental car to the edge of the bomb pit.

“You ever back up a trailer in your driveway?” Farrell asks. “Imagine doing that with a B-29.”

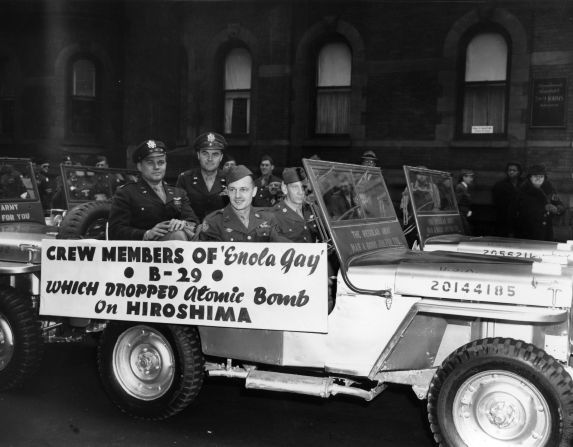

With that, we’re about to make the short trip to the end of Runway Able on North Field, the very runway the B-29, named Enola Gay, took off from at 2:45 a.m. on August 6, 1945.

The journey is a few short minutes in the car. It would have been much longer for the lumbering B-29 and its 9,700-pound (4,400 kilogram) payload.

I stop the car and line it up on the center of Runway Able, trying to recreate the movements of Enola Gay’s pilot, Col. Paul Tibbets, 75 years ago.

My co-pilot, Farrell, nods and I punch the accelerator. I am driving down the very runway where history was made 75 years ago, and as the tarmac passes below me I have goosebumps.

It’s about a two-minute drive down the runway. Farrell provides the imagery as to what Tibbets would have seen – the tents, the troops, B-29s by the dozens.

While it’s two quick minutes for me, it was far from it for the men aboard Enola Gay, Farrell says.

They were doing something that had never been done and something they believed would hasten the end of World War II and certainly change history.

“For the men on Enola Gay, it was the longest two minutes of their lives,” Farrell says.

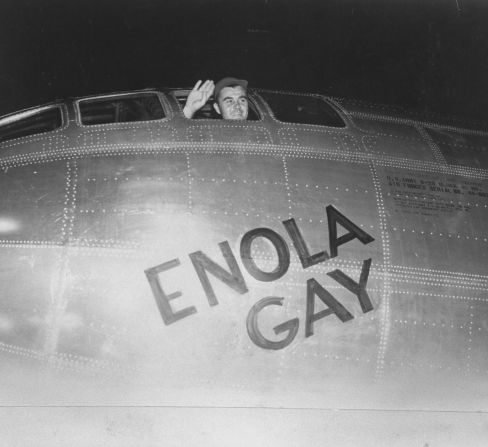

Enola Gay

You can see that airplane now in suburban Washington, DC.

Enola Gay is one of the centerpieces of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, the annex of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia.

It sits in the middle of the museum, surrounded by dozens of aircraft of all ages, from the origins of flight to the space shuttle Discovery.

As I walk up to it, seeing it for the first time during a visit in November 2019, I feel a chill.

“This is a very somber artifact,” says Jeremy Kinney, curator at the museum.

On one hand, it represents the best of the US war effort in World War II, a leap in technology, conceived, designed, built and deployed in about five years.

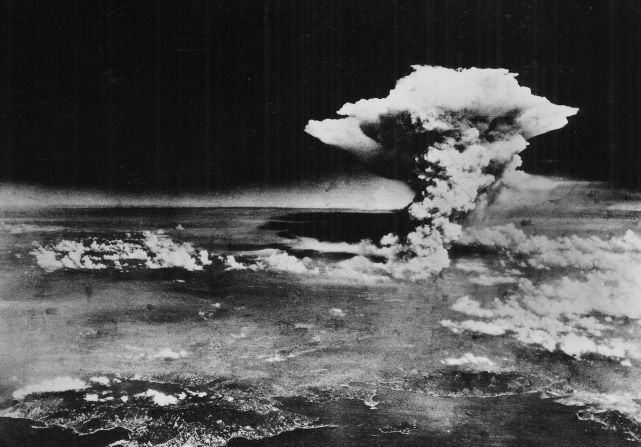

On the other, it carried the first atomic weapon ever used, one that killed 70,000 people in the first moments after it was dropped and tens of thousands more from its aftereffects.

Touring the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum's Enola Gay exhibit

“The Enola Gay has been a controversial object, for the Smithsonian and for the country,” Kinney says.

Kinney and the museum offer some interesting facts about Enola Gay:

The B-29 was designed to be an intercontinental bomber, one that could fly from the continental US to Europe in case Britain fell to Nazi Germany;

It was one of 300,000 aircraft produced by the United States in World War II, and one of only 15 B-29s specifically made to carry atomic bombs;

Pilot Tibbets picked this plane while it was still on the assembly line in Omaha, Nebraska, to be used for atomic bomb missions, but it didn’t get its name – after his mother – until shortly before leaving on its historic mission.

What visitors won’t get at the Smithsonian Enola Gay exhibit is a complete story of the bombing of Hiroshima. There are no artifacts from Hiroshima, no discussions of bomb victims or whether the use of atomic weapons was necessary.

Plans to include such content in the Enola Gay exhibit were scrapped in 1995, when, under pressure from US veterans’ groups, then-Smithsonian Secretary I. Michael Heyman said it would not include analysis, but only commemorate and honor the sacrifice of US war veterans.

To this day, the museum’s webpage on Enola Gay doesn’t mention the death toll in Hiroshima.

But standing in front of the silver-skinned bomber, Kinney says it still sends an important message.

“It gives us a lot of pause in regard to the power of the technology,” he says.

“We wanted to get this out so people could see it, people can bring their stories, their perspectives, to look at this pivotal turning point in human history – the atomic age, the end of World War II – but also this highest development of aeronautical engineering in the first half of the 20th century.”

That’s the message Toshihide Naganuma, a 50-year-old visitor to the Smithsonian from Osaka, Japan, was taking home with him.

“I was amazed about the aircraft,” Naganuma says. “It shows the technical abilities and economic strength to manufacture something like that.”

As for his feelings as a Japanese, Naganuma isn’t emotional.

“I was born after the war, so to me it’s just a part of history,” he says.

Hiroshima

Halfway around the world, where the atomic bomb killed 70,000 people with its initial blast, and left tens of thousands of others to die slowly from burns or radiation-related illnesses, that history can still be raw and its stories pull at the heart.

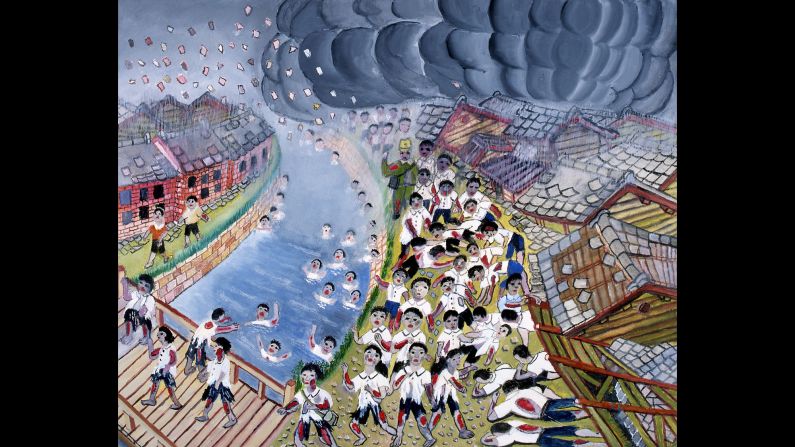

Inside the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which sits near ground zero in the Japanese city, a permanent exhibit gives details of some of the schoolchildren who were killed by the bomb.

The bombing of HIroshima

The hall is dark and silent and solemn. Behind glass cases, the portraits, the clothing, the bicycles, the dolls and the drawings of the dead are displayed with their stories.

They tell of children who wish they could sacrifice their lives for their mothers’, and of mothers thinking the knock on the front door is the child she hasn’t seen in years.

It’s hard to choke back the tears.

A short walk away is the dome, the iconic remnants of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, now known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

It’s close to a T-shaped bridge that was the aiming point for the crew of Enola Gay. The atomic bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” detonated 2,000 feet above it.

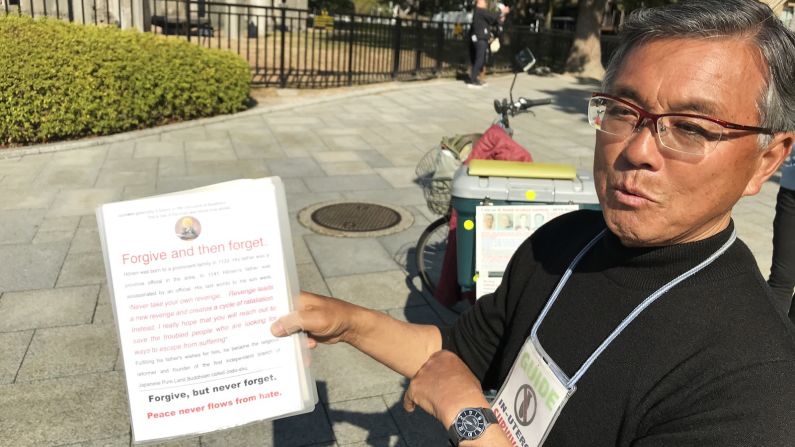

Along the sidewalk surrounding it and along the bank of the Motoyasu River, Kosei Mito has parked his bicycle and laid out his passion – documents to detail what happened here and hopefully make sure it doesn’t happen again anywhere.

Mito is an in utero atomic bomb survivor; his mother was four months pregnant with him on August 6, 1945.

Now a retired teacher, he says he has come to the dome nearly every day for 13 years, riding his bicycle the 10 kilometers (six miles) from his home.

The bike is loaded down with documentation of the bombing of Hiroshima and its aftermath. It’s in Japanese, English and Chinese, but he’ll get you other languages if you want them.

“This is my open class. I can tell everyone what they want to know,” Mito says.

He’ll pore through the laminated pages of his loose-leaf binders with any visitor who is interested. He’ll cite studies and documents from both sides of the Pacific to put together his unique – and opinionated – Hiroshima narrative, with one goal in mind: “Without knowing the historical facts, we may repeat the same mistakes again.”

If he’s busy or not around, there are several other locals who will give you a free tour of the grounds with all the historical details.

But Mito’s passion and experience are worth waiting or returning a second day for.

The 74-year-old turns to a page in one of his binders with a large quote Pope John Paul II made during a visit to Hiroshima in 1981, one that’s inscribed on a memorial inside the Hiroshima Peace Museum.

“To remember the past is to commit oneself to the future.”

Mito says those are words he lives by.

“We have no responsibility for what’s happened in the past, but we have responsibility for the future,” he says.

Visiting Hiroshima's ground zero, 75 years on

Fifty yards or so from where Mito is telling his story, a Western man sits on a bench, smokes a cigarette and stares up at the exposed superstructure of the dome.

He wears a T-shirt from Baylor University in Texas, tipping him off as an American, but Raymond Godzisz says he’s actually from Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

It’s his first visit to Japan, and before coming he had no idea what he’s seeing now existed.

Asked what it means to him, he struggles for words.

“Being an American, our country did this, but I had nothing to do with it so it’s like …

“I’m just happy they (the Japanese) don’t turn us away,” he says.

It’s clear this experience will stay with him a long time.

“I just can’t stop looking at it,” he says.

If you go:

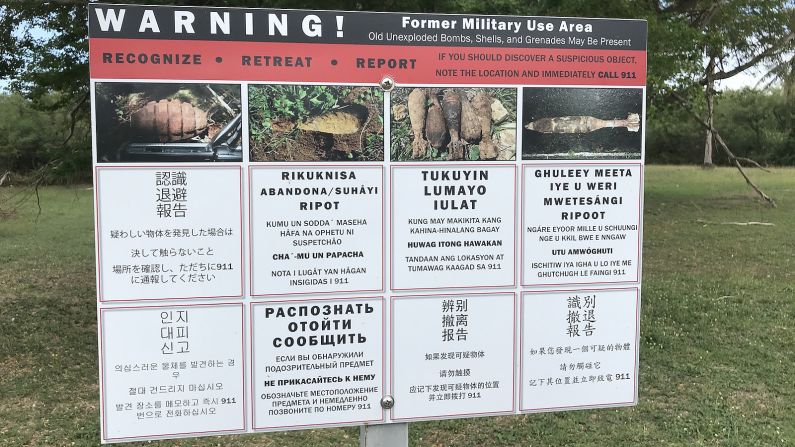

Tinian is reached via the small planes of Star Marianas Air from Saipan International Airport, which is served by international airlines from the US, Japan, South Korea and China. To get to North Field, rent a car for the 20-minute drive from Tinian Airport.

The Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center – which has reopened since the Covid-19 outbreak – is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. near Dulles International Airport in Virginia. Admission is free, but parking is $15 before 4 p.m.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, also reopened, is open daily (except December 30 and 31) from 8:30 a.m. with closing hours varying by season. Admission is 200 yen.