Story highlights

Pilots tell of three planes at Ohio's National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

Did secret spy jet spark UFO sightings near Area 51?

Heroic airmanship: Despite deadly attack, crew lands, minus 2 engines

Ex-captive recalls "angel" jet that carried U.S. POWs to freedom

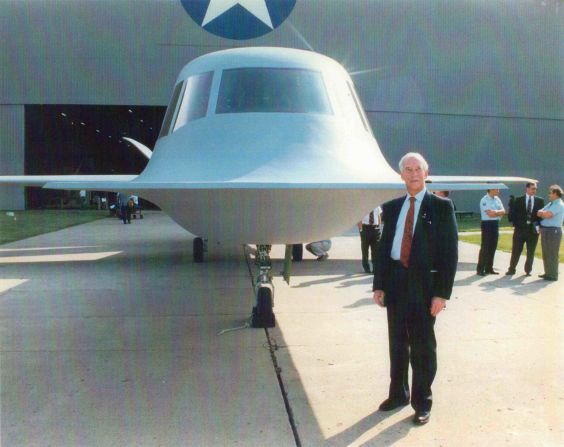

It looks like an upside-down bathtub with wings, pretty odd for a spy jet that was among the nation’s most highly classified pieces of military hardware.

As I stand in front of the plane code-named Tacit Blue at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, near Dayton, Ohio, I’m reminded that it still holds a bit of mystery.

Engineers made fun of Tacit Blue’s design by nicknaming it the Whale, but the program – declassified in 1996 – was deadly serious. It was all about stealth. Pentagon Cold War strategists desperately wanted to build planes that could evade Soviet radar.

And so the Air Force launched a “black program” to develop Tacit Blue and tested it at a secret government airbase in Nevada called “Area 51,” according to CIA documents released in 2013.

The program, which lasted from 1978 to 1985, aimed to develop a single-seater jet for battlefield surveillance.

Before last year’s document release, the government never acknowledged the existence of Area 51. For decades, a fenced-off area surrounding Nevada’s Groom Lake was rumored to be a testing ground for some of the nation’s most secret technology.

Two retired Air Force test pilots who flew Tacit Blue in the early 1980s, Ken Dyson and Russ Easter, spoke about why this plane was important and what set it apart.

Although the plane flew 135 times and was never put into production, without Tacit Blue, there would have been no B-2 Spirit bomber. The plane proved that aircraft with curved surfaces could evade radar.

“The airplane flew pretty solid, I’d say,” Dyson remembered.

Could sightings of Tacit Blue have contributed to UFO reports?

“I’m not aware of any circumstance like that,” Easter said. Dyson also says no.

If You Go ...

IF YOU GO …What: National Museum of the U.S. Air ForceWhere: Northeast of Dayton, Ohio, at 100 Spaatz St., Wright-Patterson AFB Hours: Open every day 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.; closed Thanksgiving Day, Christmas and New Year’s Day Admission: FreeTips:

• Wear comfortable shoes. This place is HUGE. • Some of the best exhibits are in a special building only accessible by bus. Space is limited. Arrive early to sign up. Bring ID. • Bags are subject to search. Backpacks, packages and large camera cases are not allowed.

But Cynda Thomas, widow of the first Tacit Blue test pilot Richard G. “Dick” Thomas, said she was with her husband in Los Angeles when an airline pilot accosted her husband during a test pilots’ banquet at the Beverly Hilton.

As she remembers it, “The pilot came over, and he said, ‘Mr. Thomas, I’m so-and-so, and I fly for Continental, and I’m sure I saw you flying the Tacit Blue – and you know, I reported you as a UFO.’ “

“Airline pilots have, over the past, reported some stuff that could have been black aircraft in flight tests,” Dyson said.

“One and a half” Tacit Blue planes were built, Dyson said, so that “if we lost one, we could have a second one up and flying in short order.” What happened to the other half of Tacit Blue? “I think it was done away with – with total respect to secrecy.”

Mechanical remnants from a related black program called Have Blue “are buried at Groom Lake,” according to a 2011 Air Force report. Groom Lake is inside Area 51, according to those released CIA documents.

“I don’t know anything at all about that Have Blue stuff and wouldn’t answer it if I did,” said Dyson, who also tested Have Blue airplanes.

Dyson is aware of the CIA documents but said he didn’t want to talk about Groom Lake or Area 51 or to even mention those places by name. “That’s just because of the secrecy that was drilled into me,” he said.

Maintaining Tacit Blue’s secrets and preventing leaks, Dyson said, was proof of the success of a tightly knit and dedicated team. Pursuing a career centered around a secret job takes discipline.

“My wife had no clue what I was doing for a long time,” Dyson said. “I just didn’t talk about it to her or to anyone else who wasn’t cleared on the program. It just wasn’t done.”

Richard Thomas also kept details about his work from his family, Cynda Thomas said, although in 1978 he did reveal to her that he was “going into the black world.”

Secrecy made professional relationships complicated at times. Associates outside Dyson’s and Easter’s secret circle wanted to hear “war stories” about what it was like to work in the world of black programs, Easter said. “Sometimes I wish we could tell more stories more freely so that some of the lessons learned could be passed on freer.”

50 states, 50 spots to visit in 2014

Three unique things about Tacit Blue

• Pantyhose made it safer: According to Cynda Thomas’ book “Hell of a Ride,” an air compressor was blowing tiny flammable aluminum shavings through inlet pipes and into the cockpit, creating a fire hazard. The engineers’ unorthodox solution: cover the inlet pipes with filters made of pantyhose, Thomas wrote. “That could be true,” Easter acknowledges.

• They created an artificial wind tunnel with a huge transport aircraft. Developers used a huge C-130 Hercules plane to create artificial winds that hit the side of the plane so they could test Tacit Blue’s performance. Dyson described it as a sort of “wind tunnel” that was set up “in the black of the night so no one could see us flying overhead with a satellite.”

• It was very hard to pilot: Tacit Blue at the time was “arguably the most unstable aircraft man had ever flown,” ex-Northrop engineer John Cashen told Air Force Magazine.

Richard Thomas died in 2006, at age 76. Cynda Thomas said her husband had been battling Parkinson’s disease.

At Tacit Blue’s 1996 unveiling ceremony at the museum, Thomas was able to sit inside the airplane’s cockpit one more time.

“That’s when they let me point my camera up the steps of the airplane to take his picture,” recalls Cynda Thomas. “I’m so thankful he got to do that before he passed. That plane was my husband’s legacy.”

8 very old sites in the New World

The plane that wouldn’t quit: ‘Spare 617’

Outside the museum’s doors, at the Air Park, sit several giant planes – each with their own stories. One of them, the Air Force Museum says, saw “one of the greatest feats of airmanship of the Southeast Asia War.”

In April 1972, a huge C130-E Hercules transport plane code-named Spare 617 was ordered to fly over a raging battle in South Vietnam and parachute-drop giant pallets of ammunition. If all went well, the ammo would resupply South Vietnamese soldiers fighting on the ground. But all did not go well.

Preparing to make his drop, pilot William Caldwell flew the plane low over the town of An Loc.

But the enemy had put a machine gun nest high above the town in a church steeple, Caldwell recalled. “So, we were just a sitting duck for him.”

Caldwell remembers machine gun fire ripping through the cockpit, smashing a circuit breaker panel and the plane’s windows. Flight engineer Jon Sanders died instantly. The attack wounded copilot John Hering and navigator Richard Lenz and damaged two of the plane’s four turboprop engines.

Gunfire ruptured a duct designed to bleed hot air from the plane’s powerful engines. The scalding air severely burned cargo loadmaster Charlie Shaub, as Caldwell put it, like a “600-degree hurricane.”

Then it got worse. The attack set fire to some of the plane’s explosive cargo.

But despite his burns, Shaub was somehow able to eject the burning pallets of ammunition. It was just in time. Seconds later, the ammo exploded as it fell to the ground. Then, Shaub astonishingly snuffed out the fire in the cargo hold. Caldwell closed the bleed air duct and shut down the damaged engines.

Next problem: how to save the wounded crew. Caldwell pointed the plane toward an air base with the best medical facilities. He would have to land a giant C-130E with only two working engines – both on the same side of the aircraft.

Things looked grim, he said, but “I got more confident with every mile we got closer to the air base,” said Caldwell.

Again, things went further south.

A hydraulics system that was needed to lower the landing gear became useless. Using nothing but sheer muscle, Lenz and cargo loadmaster Dave McAleece lowered the wheels by hand using crank handles, Caldwell said.

Caldwell landed the plane fast: pushing about 170 mph. With hydraulics busted, he had trouble steering the plane.

“I used the inboard right side engine to guide the plane down a high-speed runway turnoff,” he said.

After rolling to a stop, “I got out of the airplane,” Caldwell recalled. An airman on the ground asked, “Are you OK?” Caldwell replied, “You bastards didn’t prepare us for THIS.”

Blood Falls and other natural oddities

Three notable details about the mission

• What recognition did the crew receive? Caldwell and Shaub received the Air Force Cross, the Air Force’s second-highest award for valor.

• Did the plane have any weapons? Spare 617 flew with virtually no defensive weaponry. “We only had .38 revolvers,” said Caldwell, 70, now a retired colonel who teaches aviation management at Southern Illinois University. It was the airplane itself, he said, that helped save them. “That airplane was just as responsible for getting us home as any of the crew.”

• How hard was it to lower the landing gear? The attack knocked out the plane’s hydraulic system, forcing the crew to lower the plane’s gigantic landing gear manually. “I think it takes roughly 650 turns of that crank to get a landing gear down on both sides of the airplane. It’s an endurance thing more than strength thing.”

‘Angel’ of freedom: The Hanoi Taxi

A third piece of flying history at the museum has come to symbolize freedom for former U.S. POWs captured during the Vietnam War.

They call it the Hanoi Taxi, the first U.S. plane to ferry newly freed troops out of North Vietnam. Photos of the ex-captives taken aboard the C-141 Starlifter clearly illustrate the joy and relief the men felt that day in February 1973.

Until the POWs left enemy airspace, they had refused to give their captors the satisfaction of showing happiness for being released. When they crossed over international waters, stoic silence immediately turned to joyful pandemonium.

A few hours later, with the Starlifter in the background, TV viewers watched stunning, emotional reunions in the Philippines between the ex-POWs and their loved ones.

Maj. Gen. Edward Mechenbier, a retired Air Force fighter pilot who spent nearly six years as a North Vietnamese prisoner, rode aboard the plane as it carried him back to the United States from the Philippines.

“This plane looked like an absolute angel coming to get us,” he remembered.

Now, the plane sits at the museum’s Air Park, at the mercy of the wind and cold. Walking around the aircraft and running your hand across its metal exterior, you get a sense that you’re touching a piece of history.

“It’s a hallowed place,” said museum curator Jeff Duford. “And you can definitely get a sense of that when you step aboard it.” But right now, that’s not possible for visitors. The Taxi’s interior is off-limits, and its flight deck windows are covered.

The plane – along with Spare 617 – is slated to be housed in a new $35.4 million building in 2016. Duford says the museum hasn’t decided whether visitors will be able to board either aircraft when they move inside.

The Hanoi Taxi flew two freedom missions carrying ex-POWs out of Hanoi’s Gia Lam Airport. Overall, the aircraft’s total passengers to freedom numbered 78 POWs and two civilian returnees. The plane also flew four freedom missions from the Philippines to the United States, carrying a total of 76 ex-POWs.

For four decades, the airplane served around the world, until it retired in 2006 to the Air Force museum.

Three unique things about the Hanoi Taxi

• The plane returned to Vietnam in 2004: Mechenbier, by then a major general, flew the Hanoi Taxi back to Vietnam on a mission to repatriate the newly recovered remains of two U.S. service members who were killed in action during the war.

• It served in the Iraq War: The plane helped transfer wounded troops from Baghdad to Ramstein Air Base in Germany and to Washington for treatment at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

• It served as a disaster evacuation plane: The Hanoi Taxi airlifted survivors to safety after 2005’s Hurricane Katrina.

Like many of the museum’s other hundreds of aircraft, these three planes – Tacit Blue, Spare 617 and the Hanoi Taxi – contributed to history.

“These really aren’t airplanes anymore,” Duford said. “They’re artifacts. And so we want to make sure, as a responsible institution, that we protect those artifacts. That’s more important than anything else.”