Editor’s Note: In Snap, we look at the power of a single photograph, chronicling stories about how both modern and historical images have been made.

For the Japanese artist Kensuke Koike, every photograph becomes a puzzle. In his work, Koike takes vintage portraits from thrift stores and flea markets — many bought in and around Venice, where he is based today — and meticulously cuts them with a small blade to rearrange their elements, producing playful and often mind-bending results. A figure’s head might be removed and placed beside them, or have their features distorted or disordered: Faces become diamond patterns, whorls or portals; couples gazing at one another exchange their eyes. The only rule Koike works to is “no more, no less,” the artist explained, meaning he must use all parts of the original image, and doesn’t add anything new.

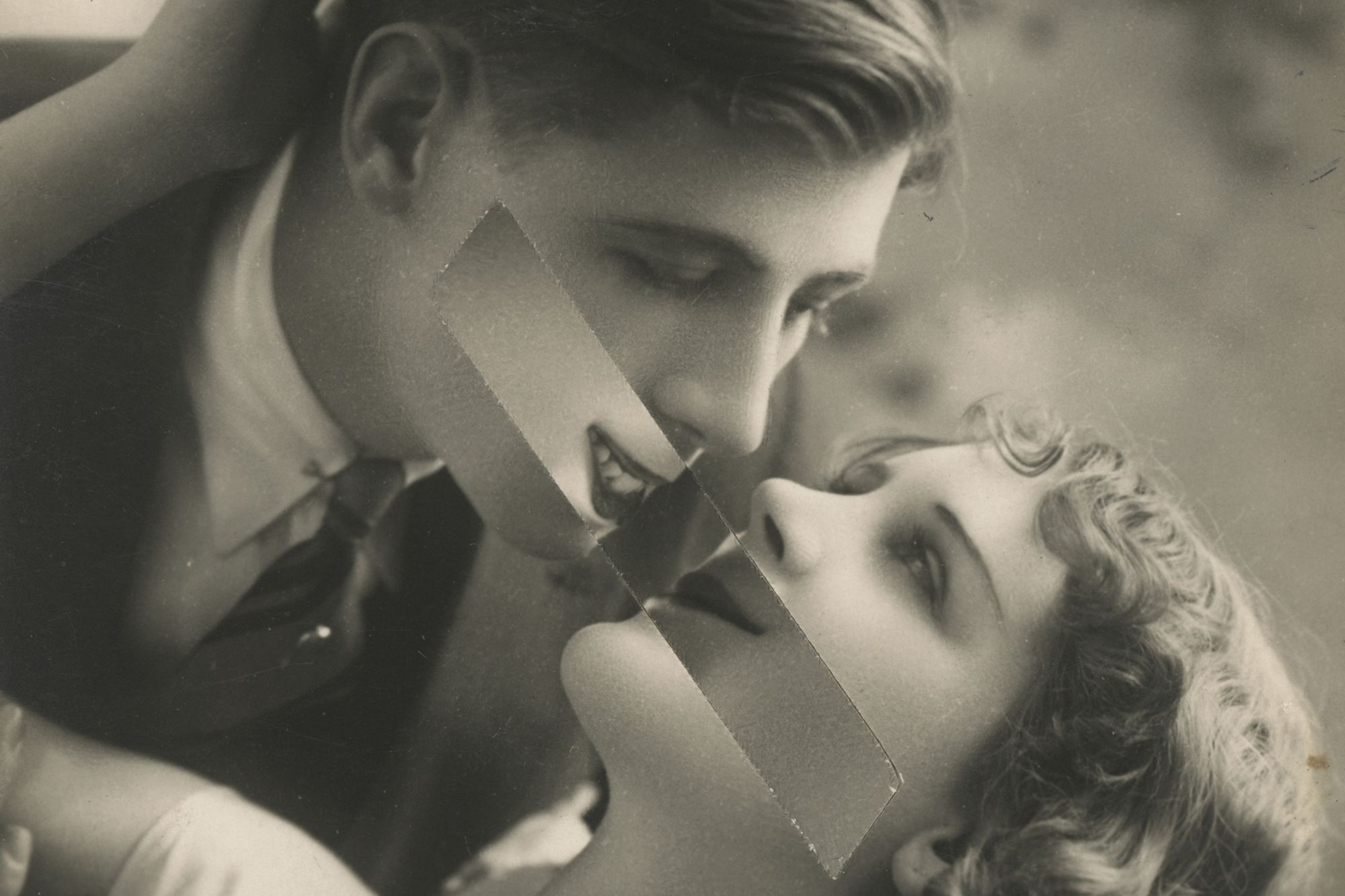

The formal studio pictures and postcards with which Koike works often showcase feature glossy romantic portraits of anonymous couples. In one such postcard, which he discovered during an artist’s residency in Naples, a reclining woman with her hair in 1920s finger waves looks up amorously at her male partner, who is swooping in for a kiss. With their lips frozen just inches from one another, Koike cut a single panel stretching from mouth to mouth and flipped it, so that her sultry, parted mouth becomes a goofy grin on his face. Reversed, his thin lips, previously downturned, become her own small, knowing smile — seemingly changing up the power dynamics of their relationship.

Koike titled the new piece “Say Cheese,” explaining to CNN that he simply wanted to give levity to such “serious expressions.”

But the adjustment to the image is deceptively simple, masking an intricate, weeks-long process that involved Koike making upwards of 100 variations on copies of the photograph before choosing a final direction.

“I have only one chance to cut the original photo. So before I cut, I always do many, many tests before,” he explained. “Everything must be perfect. Sometimes it is only (cutting) one line — but for me, it’s very emotional.”

In other test versions of “Say Cheese,” Koike switched the couple’s faces or body parts, but eventually reduced his edits down to that single, small detail, a process which he has demonstrated in a popular Instagram video. Rose Shoshana and Jaushua Rombaoa, who run Rosegallery in Santa Monica, California — which is currently exhibiting a selection of Koike’s work in the group show “Fragmented Lucidity” — told CNN that Koike excels at shifting perceptions through his modifications.

“(He) takes the stylized, prototypical image of romance and passion, strips away its romanticization and sentimentality, and subverts it into a jestful, whimsical play on human connection,” they wrote over email. “Kensuke’s world is one that is similar, but adjacent, to ours. It is unexpected and lively, blurring the lines between reality and imagination.”

As he works on an image repeatedly, Koike said he finds himself creating stories about the lives of the people in the portraits, though he keeps those musings private. He treasures them — photos of unknown sitters are often not coveted by vintage image collectors, he said, and their identities are lost in estate sales and resales. He doesn’t want the photographs to “disappear,” he explained, so he gives them another life in his studio.

After frequenting many of the same thrift shops over a period of a few months, their owners caught wind of Koike’s interest and began reaching out to him to offer their caches of vintage images, he added. While he only works with around 10 photographs a year, he now has some 50,000 in his possession. He laughs at how many he’s accumulated.

“I could never say no,” he said.