Editor’s Note: Angela Brady is a director of Brady Mallalieu Architects in London, an award-winning sustainable architects practice based in London for over 25 years. She is past president of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Brady is a design champion, a television broadcaster on architecture and design, and promotes women in architecture.

Story highlights

Zaha Hadid's work was flamboyant, stunning and distinctive

She was tough and uncompromising, a female architect to be looked up to

One of her famous buildings is the London Aquatics Centre

I heard the sad news three minutes after it went up on Twitter. My first reaction was of shock, that our great dame of architecture was cut down at the height of her career, when she had so much more to give us with her stunning architecture and her sharp wit.

We lost someone who was also a great role model for women in architecture.

She said it was “still tough for (her), too, as a woman architect.” But she was tough and she made it to the top in a male-dominated profession designing some of the key icons around the world. She was someone who didn’t like to compromise her ideas. In fact, in a recent Oxford Union interview she was asked, “What do you do when you have to compromise your design for practicality?”

Zaha’s swift answer was, “I don’t like the word compromise to start with. We know we are professionals and we know on every project we have to be smart in the way we interpret our clients’ (wishes). … And as long as you maintain the central idea of the project, and can adjust the work to suit, in some cases it makes the work better – if you have to go around a certain problem.”

This is so true and particularly for Hadid’s organic type of fluid architectural forms. Hadid’s buildings certainly don’t look compromised; they are full of vigor and form and new ideas. Some were certainly difficult to build, as new architectural design ideas need new ways of building.

There was a time when she found it difficult to get commissions in the United Kingdom after she moved there in 1970 at age 22. Her first international building was the award-winning Vitra fire station in Germany, which opened in 1993.

Even in the past decade she has many fine buildings to her practice’s name, not only in the UK – such as the Serpentine Galleries – but all over the world.

One of my favorites is the London Aquatics Centre at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, built for the 2012 Games.

While I was president of the Royal Institute of British Architects from 2011 to 2013, I managed to film Zaha’s team at the aquatics center when it was in its larger form with “wings” attached. It remains today in its slimmed-down legacy version as an iconic building sitting well in its landscape.

It is a very popular building that continues to make its mark with the public.

I once interviewed Zaha about her work and being a female architect at the top of her profession. It was great to meet her family and close friends at the Damehood party held at the Royal Academy in London in 2012 and see her in a relaxed and friendly mood.

She could be charming, but no one knew when interviewing her how she would react to the questions. There were many surprise responses.

Zaha, who was born in in Baghdad, was a powerhouse and she even dressed in the same way as her flamboyant buildings, with pleated silk gowns and dresses by Elke Walter, highlighted by exotic jewelry.

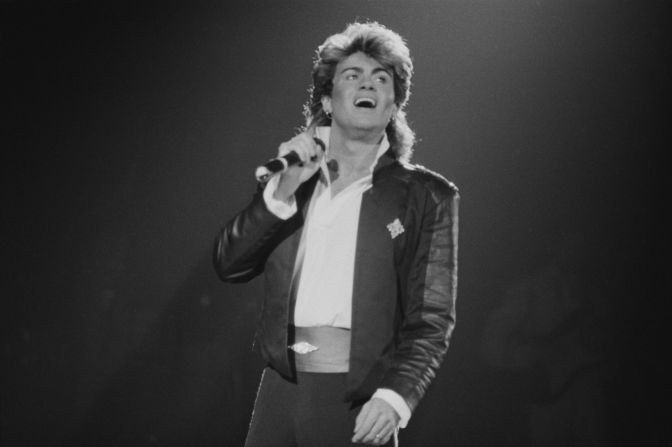

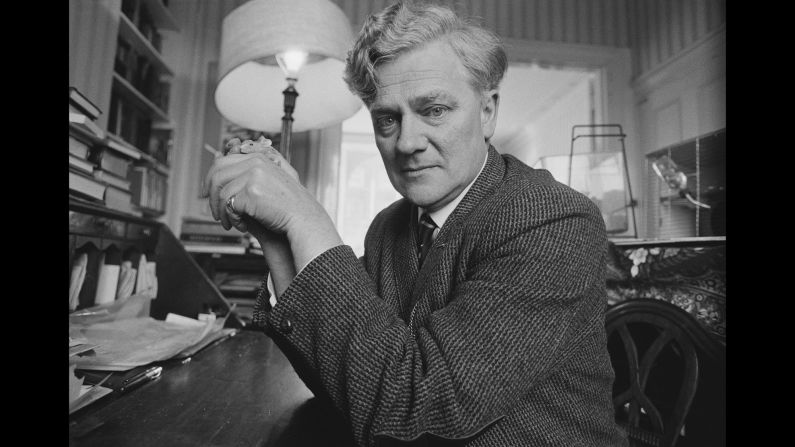

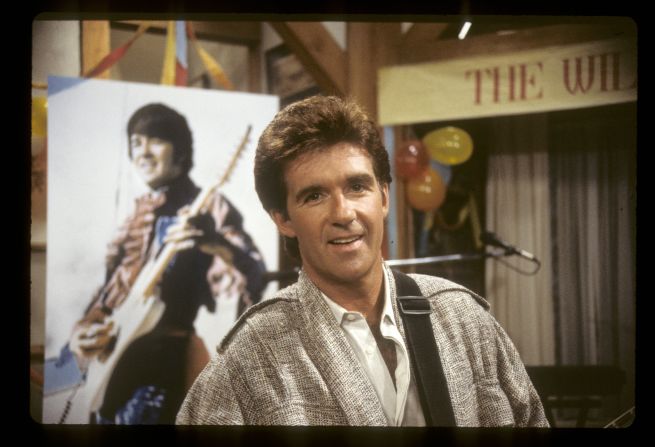

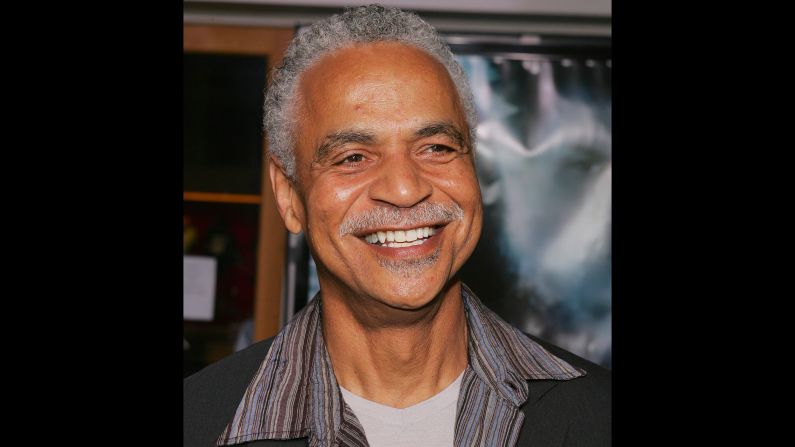

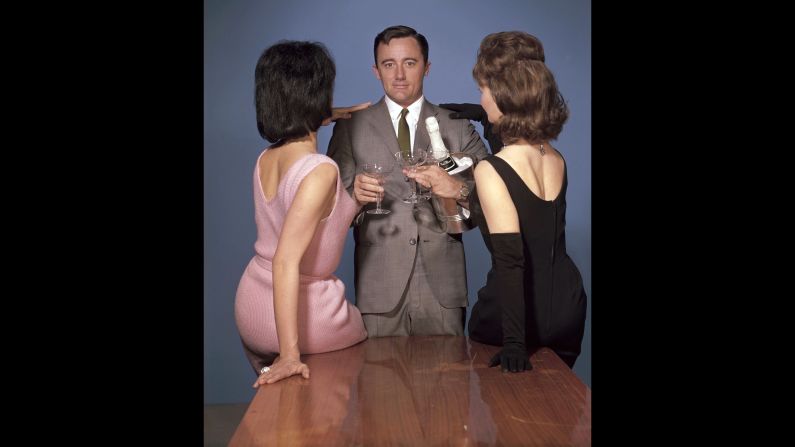

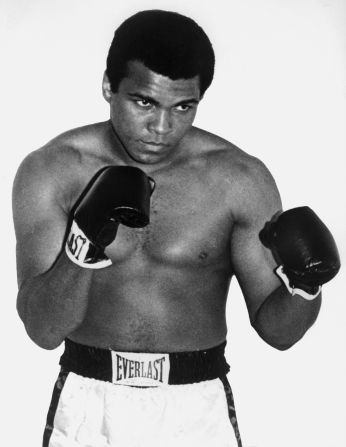

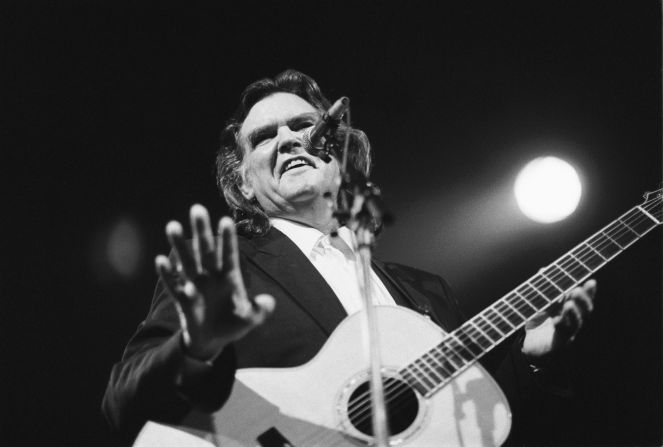

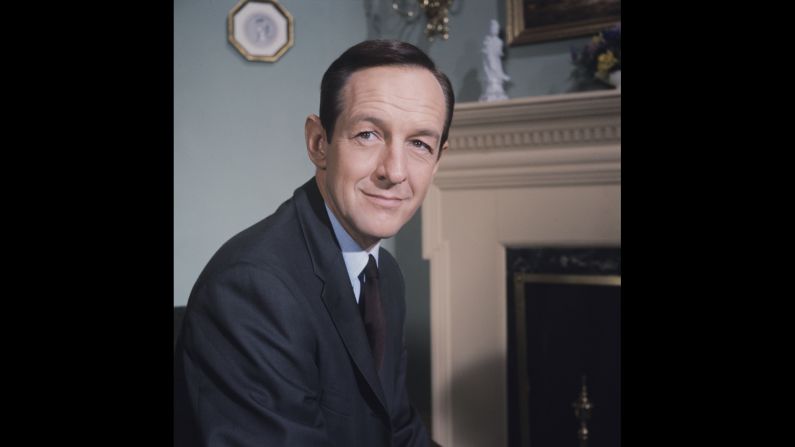

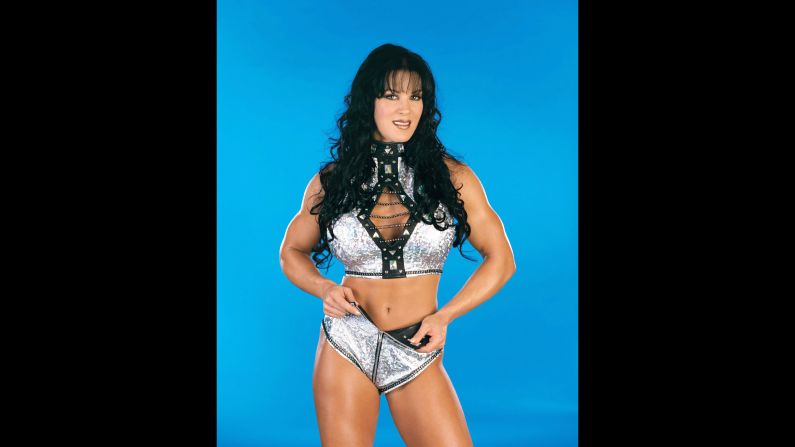

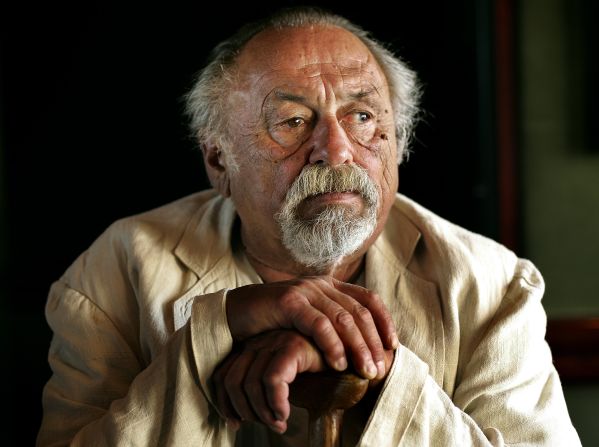

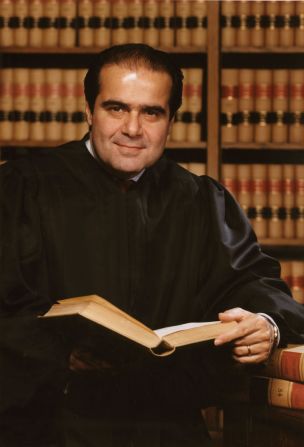

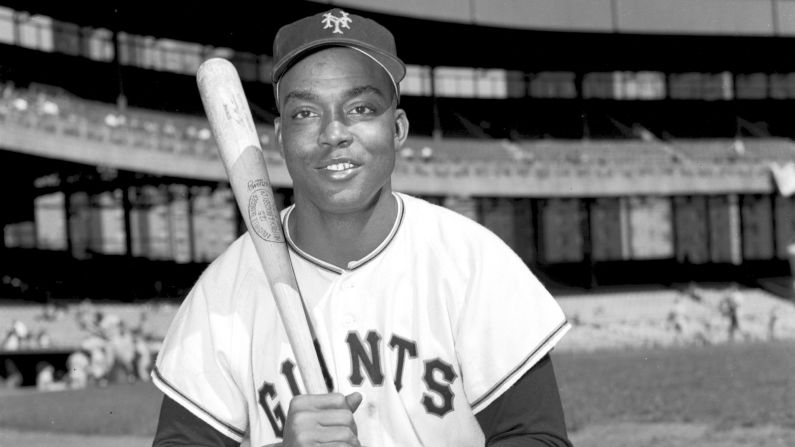

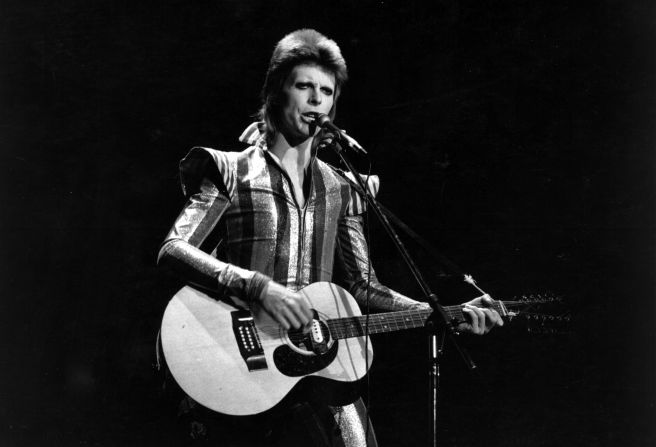

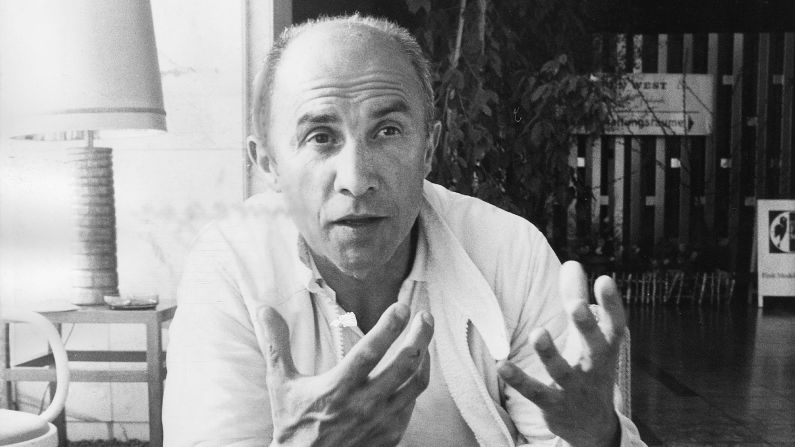

People we lost in 2016

As an architect she had a far-reaching design influence from architecture to interiors to furniture. Her jewelry designs for Danish design house Georg Jensen, launched recently at Baselworld, are almost like mini versions of her architectural forms – curvilinear, sensuous and unique.

As a female architect she was a role model to many women and will continue to inspire the rising generations who need to stand up for themselves when under pressure and to work around problems instead of compromising.

Zaha was the Architects’ Journal winner of the Jane Drew prize for women in architecture in 2012. The judges said: “Hadid has broken the glass ceiling more than anyone and is practically a household name. Her achievement is remarkable.”

Zaha was also the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker Prize, and won the Stirling Prize in 2010 for the MAXXI museum in Rome and in 2011 for the Evelyn Grace Academy in London in 2011.

I was chairing the judging panel in 2011 and we walked around the Evelyn Grace Academy in Brixton. It was a revelation to see how an inner-city school could be transformed into this exciting and dynamic school. The children absolutely loved it and school standards improved. That is the best accolade to educational design – better results – from enjoying the space you are in.

In February, Zaha was interviewed for the famous BBC Radio 4’s “Desert Island Discs.” Speaking to presenter Kirsty Young, she said, “I don’t really feel I’m part of the establishment, I’m not the outside, I’m on the kind of edge, I’m dangling there. I quite like it.”

I think this is quite true.

Zaha Hadid’s buildings are a brand on their own, stylish and distinctive.

We are still in great shock from the news of the death of our wonderful dame.

In a recent BBC Arts project, Zaha was asked to write a postcard to her younger self.

She wrote: “Your success will not be determined by your gender or your ethnicity but only by the scope of your dreams.”

What beautiful words and how she liked to dream. She was a true pioneer and a great visionary.