Editor’s Note: In Pursuit of Rare is a new series telling the stories of the master makers who deal in the most precious things on earth.

Every day Wallace Chan “communicates” with the universe, turning rough, ancient gemstones into extraordinary pieces of jewelry.

“I learn from the color, the shape, the light,” Chan says, rotating a block of tourmaline in his hand. “When you cut, when you polish, it’s like music. The light goes through the stone, reflects, and it’s like a ballet.”

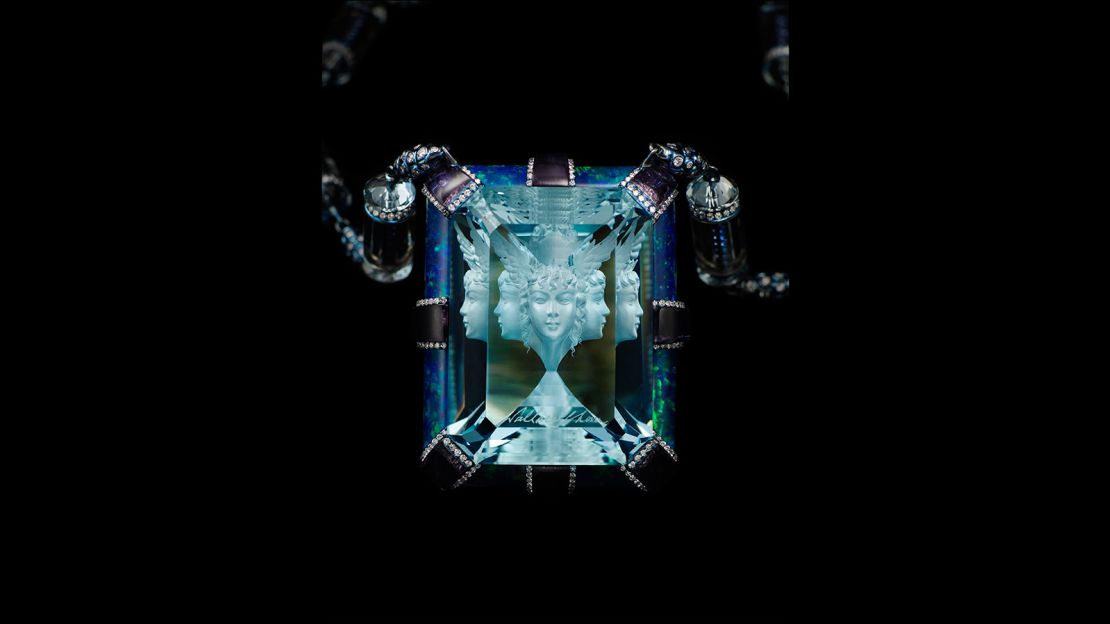

Since founding his studio in 1974, the artist’s work has become legendary, due to his inventive and painstaking approach to gem carving. For example, his signature “Wallace Cut,” is a complex technique developed over several years which allows him to create detailed images inside gemstones, producing a three-dimensional effect.

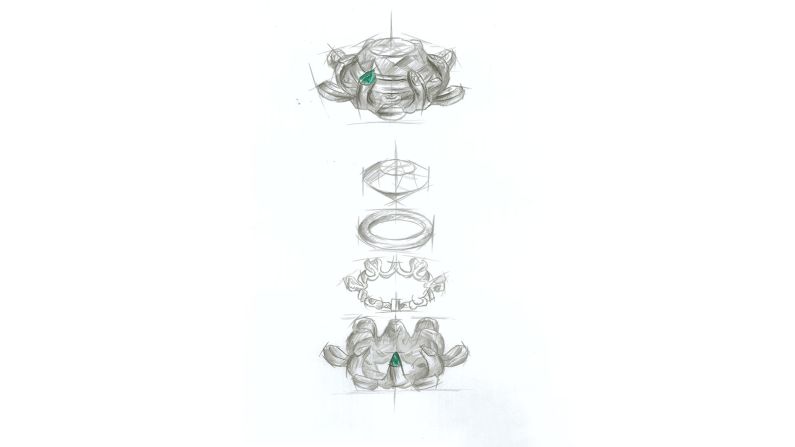

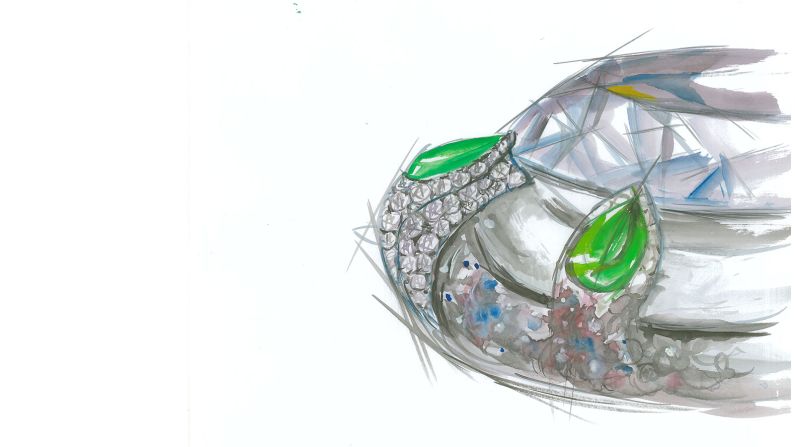

In 2014, Hong Kong jewelry giant Chow Tai Fook invited Chan to create a lavish neckpiece from over 11,000 diamonds, alongside green jadeite and so-called “mutton fat” white jade beads. The design process took a team of 22 people and 47,000 hours to make, resulting in a uniquely modular piece that could be reconfigured and worn in 27 different ways.

Trace the journey of one of the world's rarest and largest diamonds

“We need innovation,” Chan says, citing influences from across Eastern and Western cultures, philosophy, nature and advanced technology. “If there is no danger, and we are only enjoying the craftsmanship from yesterday, we will only be enjoying the past. There will be no tomorrow.”

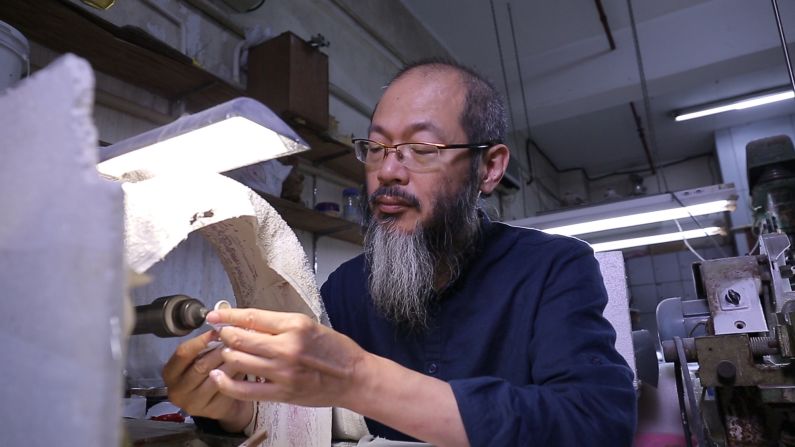

At his workshop in an industrial Hong Kong neighborhood, Chan unveils his latest invention: a type of porcelain that he has been developing for more than seven years. The material, which he claims is five times stronger than steel in small, jewelry-sized quantities, can be used to make wearable objects. While the porcelain’s strength is yet to be independently verified, he drops a porcelain ring onto a hard floor as a demonstration.

It doesn’t shatter.

“A creator doesn’t only pursue ephemeral works, but creations that can last for eternity,” Chan explains, pointing to the various stages of porcelain-making in his laboratory.

First, raw components are carefully mixed and heated at a consistent temperature. This results in a chalky white disc which can be chiseled and carved into rings or other items of jewelry. These unfinished forms are then fired in a kiln, before being rigorously polished and buffed so that, “the light appears to float on the surface,” as Chan puts it.

The porcelain is then joined with titanium fixtures that help set the gemstones.

The idea of creating “unbreakable” porcelain, as it is widely referred to (although Chan interjects that “everything” is ultimately breakable), can be traced back to his childhood.

Growing up in a poor family, Chan recalls that he and his siblings were only allowed to eat with plastic utensils, while his parents used porcelain. One day, while his parents were out, he went to play with a porcelain spoon and accidentally smashed it to pieces. He was punished for it, but the incident sparked a lifetime of curiosity toward the properties of porcelain.

After years of experimenting with other materials and gemstones, Chan keeps returning to this material, seeing it as the epitome of luxury.

“For traditional (setting) materials, after you wear for a year, its shine will fade,” he says. “But porcelain is forever.”

“Ten, twenty, a hundred years and it will still shine. And when you wear it, you can feel its intimacy,” he adds, demonstrating how, as a ring, the material seems to hug his fingers.

Chan is still in the process of refining the material and techniques, but he says that dental experts, watchmakers and material designers have all expressed interest in his invention.

“I want to put the wonder out there,” he says. “To show the potential and possibilities of such a graceful, cultural and historic material to the world.”