On Sunday, Black Lives Matter protesters in Bristol, UK, pulled down a statue of 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston and rolled it through the streets before dumping it, unceremoniously, into the River Avon.

Some applauded the move, while others decried what they called “mob rule.”

With a colonial history spanning centuries – and a mania for erecting statues in the 19th century – Britain’s towns and cities are dotted with monuments to figures like Colston.

For some, the statues have melted into the background of daily life, but many people are now questioning whether they should still stand on their pedestals.

Around the country, various local authorities have already started to act to remove statues or consider their future.

On Tuesday, the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, announced a commission to examine the future of landmarks around the UK capital, including murals, street art, street names and statues.

The Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm is aimed at improving “diversity across London’s public realm, to ensure the capital’s landmarks suitably reflect London’s achievements and diversity.”

On Thursday, a local council in Dorset, southern England, announced it would remove a statue of Scouts founder Robert Baden-Powell following police advice it was on a “target list for attack.” Critics of Baden-Powell say he held homophobic and racist views.

Actions against statues linked to the slave trade and imperialism have also gained traction in other parts of Europe, with protesters in Belgium defacing several monuments to King Leopold II in recent days and one removed from a square in Antwerp on Tuesday.

In the US, a string of Confederate statues have been removed by authorities in the wake of widespread protests over the death of George Floyd.

While these actions have divided public opinion, they feed into a growing conversation about what should happen to statues of individuals like Colston, who profited from the suffering of so many.

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill, Britain’s wartime prime minister, is held up as an example of inspirational leadership, presiding over the country’s defeat of Nazism. In 2002, he topped a nationwide BBC poll to find the 100 Greatest Britons, and his portrait currently appears on the UK’s £5 note.

However, he is also known to have held views relating to societal hierarchies that would be regarded as racist today, and his policies have been blamed for causing the 1943 Bengal famine, which is estimated to have claimed more than three million lives. In March 2019, a study used soil analysis for the first time to argue that the famine was caused by Churchill’s policies rather than by serious drought.

During Sunday’s Black Lives Matter protest, a statue of Churchill standing in London’s Parliament Square was daubed with the words “… is a racist.”

Cecil Rhodes

Cecil Rhodes was one of the leading figures in British imperialism at the end of the 19th Century, pushing the empire to seize control over vast areas of southern Africa, first as a businessman and later as prime minister of Cape Colony in what is now South Africa.

He is immortalized in a statue outside Oriel College, part of the University of Oxford.

In 2016, the college refused to remove the work despite concerted pressure by the Rhodes Must Fall in Oxford campaign group, which has continued efforts to get it taken down.

“There is no place for statues that venerate vile anti-black racists in South Africa, the US, Bristol or Oxford,” the group tweeted on Sunday, inviting people to attend a protest at the college.

On Tuesday, hundreds of protestors thronged the streets outside Oriel College, chanting “take it down.”

They took a took a knee, fists in the air, and stayed silent for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time that a police officer held his knee on George Floyd’s neck.

“Now is the time to change and do things in a different way, rewriting history,” said Ester Fortes, 27, who had traveled from Portugal to visit her sister. “And if we have to take a statue from there and put it in a museum, so be it.”

Joe O’Callahan, 18, said the statue “shouldn’t still be there.”

“In this country, there is such an ingrained, systemic racism that hasn’t been questioned or looked at or dealt with for far too long,” he said.

“His involvement in the colonization of South Africa, his belief that the Anglo-Saxon race was superior, and what he called the ‘savage’ or ‘barbarian’ African race was supposed to be a subject race and ruled over by the whites – that’s just not right.”

Oriel College said in a statement Tuesday that it “abhors racism and discrimination in all its forms.” The college said it supports the right to peaceful protest and believes Black Lives Matter.

“As a college, we continue to debate and discuss the issues raised by the presence on our site of examples of contested heritage relating to Cecil Rhodes,” the statement added.

Oxford University did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.

In 2015, a statue of Rhodes was removed from the campus of the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

“He represents the former colonial representation of this country – supremacy, racism, misogyny,” said Ramabina Mahapa, president of the student group that led the campaign to remove the statue, at the time.

Robert Milligan

On Tuesday, a statue of Scottish merchant and slave-owner Robert Milligan was removed from the Docklands area in east London, according to local authority Tower Hamlets council.

Milligan, born in 1746, was the driving force behind the construction of London’s West India Docks, built in part to trade in slave-harvested goods from the Caribbean. A statue of him stood outside the Museum of London Docklands.

“Tonight, we have removed the statue of slave trader Robert Milligan that previously stood at West India Quay,” Tower Hamlets council said in a statement.

“We have also announced a review into monuments and other sites in our borough to understand how we should represent the more troubling periods in our history.”

London Mayor Sadiq Khan welcomed the move in a tweet.

“It’s a sad truth that much of our wealth was derived from the slave trade – but this does not have to be celebrated in our public spaces,” he wrote.

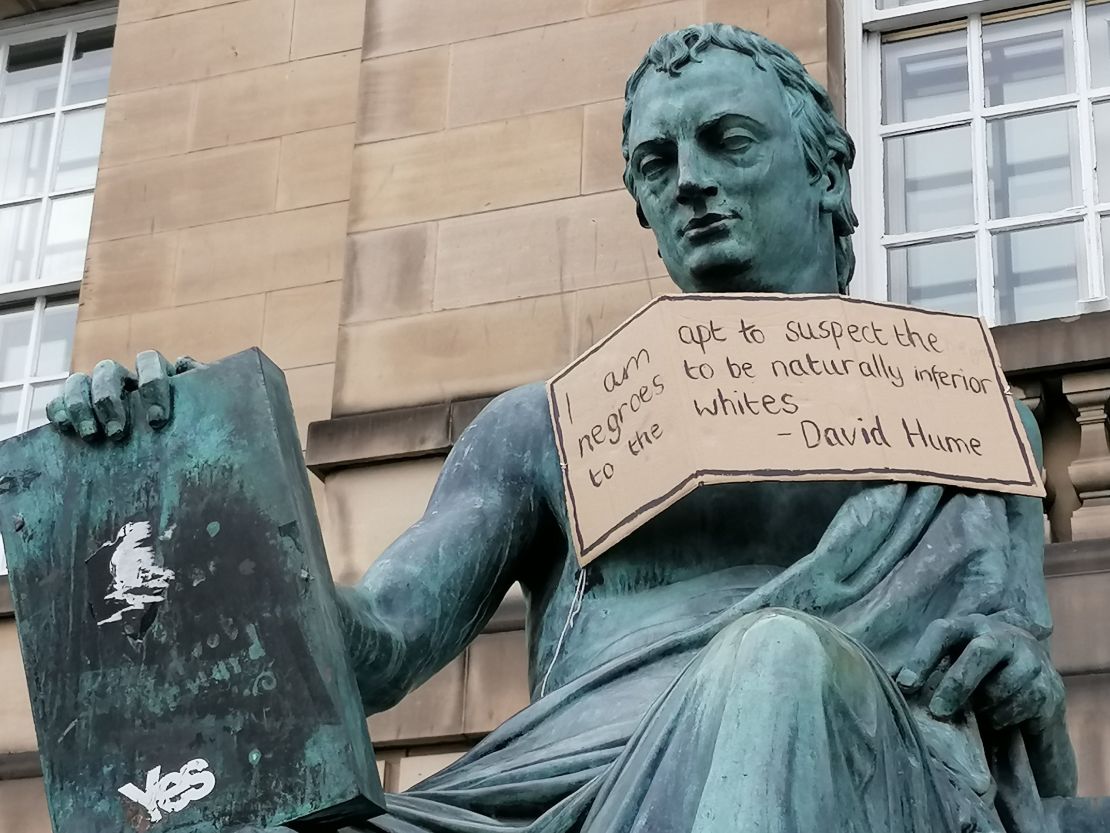

David Hume

In Edinburgh, a statue of the 18th-century Scottish philosopher David Hume was adorned with a placard quoting his views on white superiority.

Hume is considered one of the foremost thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment, and his bronze statue sits on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, the main thoroughfare of the city’s Old Town.

But Hume’s reputation has become tarnished in recent years, with increased focus on his views on race. The sign left on the statue features a line from Hume’s essay “Of National Characters” saying that he “is apt to to suspect the negroes … to be naturally inferior to the whites.”

Henry Dundas

A statue of Scottish politician Henry Dundas stands atop the Melville Monument in the city of Edinburgh.

Dundas, who held a number of government positions, including Home Secretary, is known for supporting the delay of the abolition of slavery towards the end of the 18th century.

The monument was graffitied during Sunday’s protests, and an online petition is now calling for Dundas’ statue to be removed, and for the streets named in his honor to be renamed.

Campaigners are instead recommending that the streets be named after Scottish-Jamaican slave Joseph Knight, who successfully freed himself in the courts by proving that Scots law did not recognize slavery.

On Monday, Edinburgh authorities announced that a plaque will be added to the monument, highlighting the city’s history of slavery.

A meeting will be held with experts and historians “with a view to agreeing a new form of words as quickly as possible,” Edinburgh city official Adam McVey said in a statement.

“We need to take action as a city now to tackle racism and that includes acknowledging the involvement of some of our city’s historical figures in the slave trade and the failure to abolish it sooner.”

Graffiti has also appeared on a statue of Henry’s son, Robert Dundas, the 2nd Viscount Melville. “Son of slaver and Colonialist Profiteer,” reads a tag on the base of the monument, which stands on Melville Street in Edinburgh.

Different approaches

There have also been calls to remove statues dedicated to Admiral Horatio Nelson – who famously triumphed over Napoleon and is now memorialized atop a column in London’s Trafalgar Square – because of his opposition to the abolition of slavery.

Similar appeals have been made about depictions of William Gladstone, the former prime minister who helped his slave-owner father claim compensation from the British government after the trade was outlawed.

Tearing down statues is a time-honored form of protest, from the toppling of statues of Lenin when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989 to the fall of Saddam Hussein’s monument in Baghdad in 2003.

These instances of destruction were widely applauded in the Western world, but recent campaigns to remove statues of controversial figures in places like the US and UK have divided public opinion.

An alternative approach was taken in Paraguay, where artist Carlos Colombino was asked to reimagine a statue of former dictator General Alfredo Stroessner, who ruled the country from 1954 to 1989. Instead of simply destroying the monument, Colombino encased some of its most recognizable parts between two huge blocks of cement as a memorial to victims of the dictatorship.

CNN’s Niamh Kennedy, Sarah Dean, Mick Krever, Nic Robertson, Richard Greene and Martin Bourke contributed to this report.