Editor’s Note: Artist Takashi Murakami is CNN Style’s latest guest editor. He has commissioned a series of features on identity.

The origin of my art lies in my experiences during the first half of the 1970s, when Japan was still rebuilding itself after losing World War II. The country was in a resurgent mood. Western paintings were being brought into the country, and going to exhibitions had become a very popular pastime. Every Sunday, my parents would take us to see these works, and I detested the experience.

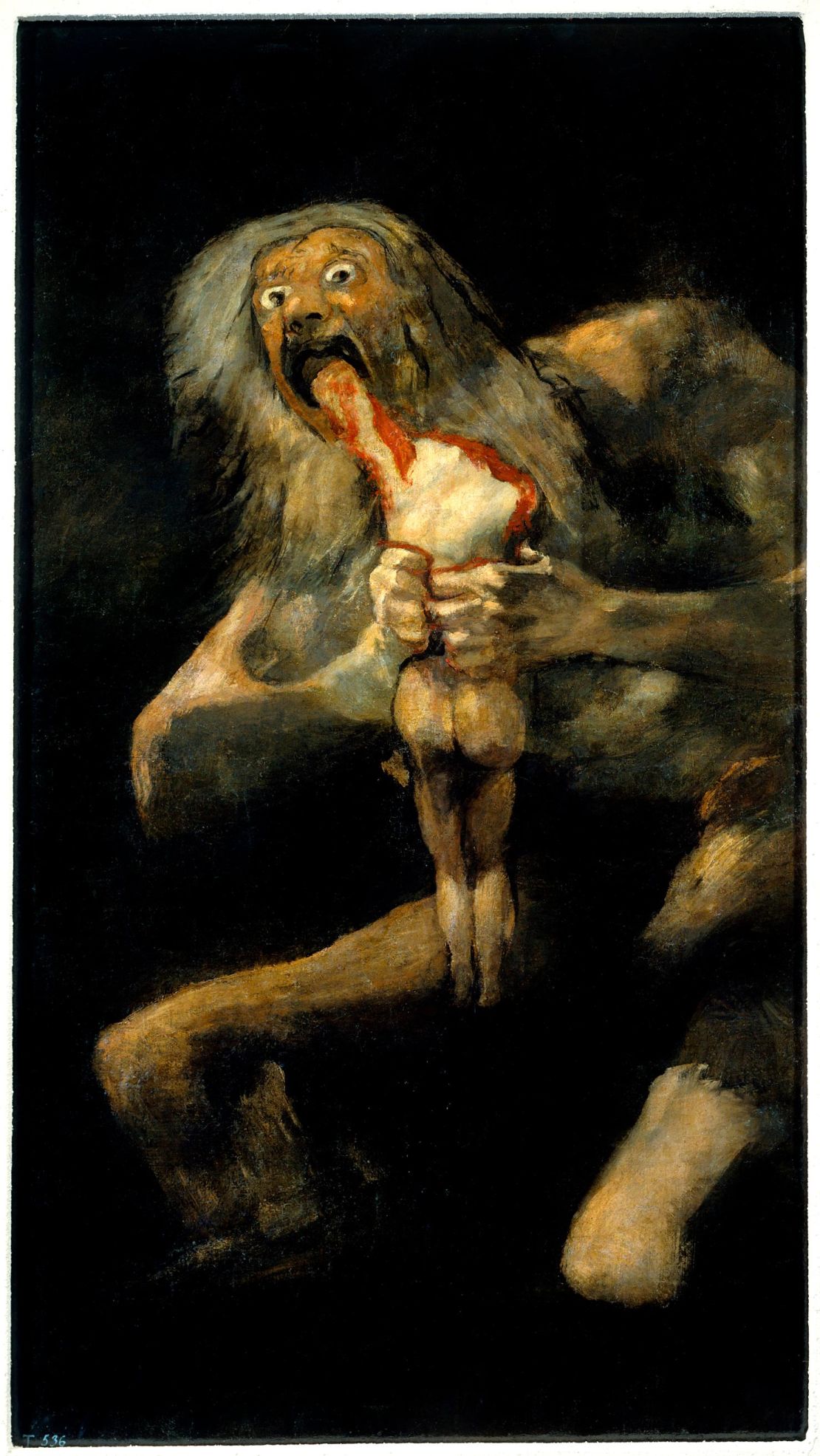

As a child, looking at paintings was absolutely boring. One standout memory was when, around the age of 8, I had to wait in line for three hours with my family, just to see the Spanish artist Francisco Goya’s painting at a museum in Tokyo. The work depicted Titan Cronus (or Saturn) eating his own children. The image was haunting and kept me up for many nights after. I think this profound experience, or trauma, formed the basis for my act of painting to this day. It taught me that if my work doesn’t move people and induce a “wow!” then it’s all for nothing.

Once I started grade school however, reading manga and watching TV anime became more important to me. No longer forced by my parents to go look at paintings, I became obsessed with “Ultraman,” robot anime and sport-themed manga about boxing and baseball. I believe these experiences have a lot to do with how I now make films and animations, alongside paintings and sculptures.

In seventh grade, I fell into a hole in the ground and broke my skull and some bones in my right hand. I couldn’t go to school for a month and subsequently failed to catch up academically. I ended up at a high school with a dismal academic record, where I couldn’t study and had nothing to look forward to. I grew even more consumed with animation and manga, turning into a geek, or so-called “otaku.”

In my senior year of high school, I met with my teacher to discuss applying to universities, and he declared that it would be impossible for me to get into any of them, no matter how low I set my sights.

Figuring that I had no choice but to go to an art university, which would admit students regardless of academic achievements, I completely gave up on education, rushing headlong into becoming a full-fledged otaku.

It was around then that “Star Wars” was released in Japan. The sci-fi animations and manga influenced by the film still nourish my creative work to this day. I also recall that at about the same time, Hayao Miyazaki, now the maestro of animation, directed his first TV animation series “Future Boy Conan.” While the designs of his animations were super simple, they were able to convey such complex emotions. I was captivated by Miyazaki’s worldview.

Having failed at entrance examinations for art universities, I had to spend two years reapplying. During that time, I would wake up at 5:30 a.m. to go to a preparatory school, and after getting out at 5 p.m., my friend and I would go to another student’s place and draw and paint until midnight.

I was eventually accepted into an art university, but in order to get in I had to select the least competitive subject and study the history of traditional 20th century Japanese painting, or “Nihonga.” This section was extremely dull and I hated being there every day.

By then, Japan was in the midst of the so-called bubble economy, and numerous pieces of contemporary art were being imported and presented as new modes of creative expressions. Naturally, I was drawn to these cutting-edge artistic forms. After seeing the exhibition of works by Shinro Ohtake, who was greatly influenced by the “New Painting” artists (particularly Anselm Kiefer and Sigmar Polke), I felt as though I was hit in the head by a hammer. I began obsessing with the question of “What is contemporary art?”

As there were no authoritative texts to refer to in Japan, where contemporary art was just starting to be imported, I decided that I had no choice but to go to New York and visit the Museum of Modern Art.

MoMA was hosting a retrospective of Anselm Kiefer then. I was so utterly awed by his painting “Osiris and Isis,” with an enormous dark pyramid as its subject, that I shed tears. Jeff Koons also had a show at Sonnabend Gallery and I got to see his famed porcelain sculpture of Michael Jackson. I couldn’t even begin to grasp its significance or value.

I dove into this very art scene after moving to New York, but by then Nihonga, the genre I had despised, had become the basis of my artwork. From then on, I have explained the background of my art and its production consistently using the term “Superflat,” the concept I came up with by overlaying the painting style of creating a completely flat surface with the cultural predicament of post-war Japan.

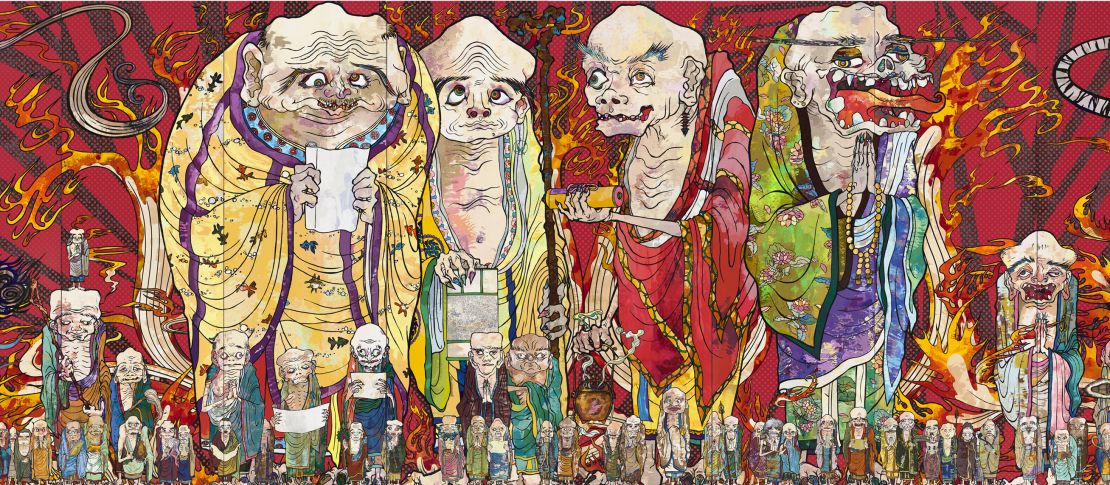

The earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan in 2011 was a big turning point for me. Faced with the reality in which tens of thousands of people could be killed in an instant due to a natural disaster, I suddenly and completely understood why, in Japan, people believed in multitudinous gods instead of monotheistic religions. I took a particular interest in the worship of 500 arhats, the enlightened figures in Buddhism, and started to expand my scope of expressions by painting, for example, a 100-meter-long work with catastrophe as its theme.

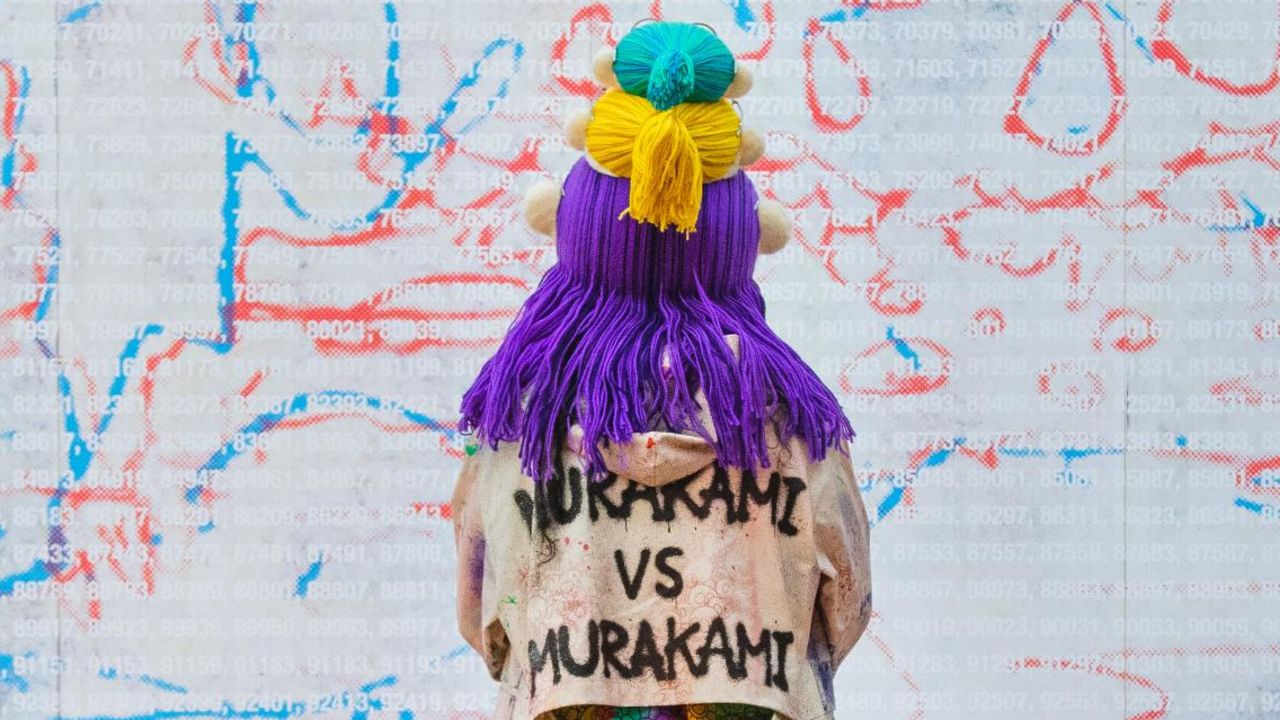

Once I started to have a good understanding of contemporary art, I also began collecting antiques. I wanted to know why we humans collect and, in particular, why we collect art. Before long, I became a collecting addict. When I obtain an artwork, I experience a very strange illusion where my brain synchronizes with the details of the work, such as the artist’s brush strokes and pencil marks. My most recent exhibition, “Murakami vs Murakami,” which opened in Hong Kong, has a whole room dedicated to items from my bizarre art collection.

'Murakami vs Murakami' exhibition

I currently run a company with 200 or so employees, give or take, depending on projects we’re working on. At first, I was just employing a few people as my painting assistants, but I had the obligation to pay taxes on their salaries, so I hired an accountant, and then I had to hire someone for HR because many people started coming and going, and so on. In the beginning we barely had enough to eat each day, but now we have become an ordinary small company. It’s such a source of stress for me, because the work of producing art and that of running a company totally conflict with one another.

On the back of each of my own paintings, there is a list of staff members who were involved in its production. My intention is to make it possible for anyone to research who had a hand in making these artworks long after my staff and I are gone. I am often criticized, however, that I am exploiting labor and creativity by working collaboratively with my assistants, which deflates me to no end.

Film and music productions are widely accepted as collaborative processes, but the presumption that a painting must be created by a lone artist persists – even if, historically, artists like Michelangelo produced his works in a workshop setting.

In the title of my new exhibition in Hong Kong, “Murakami vs Murakami,” I suggest that one “Murakami” might be the personal name that has become a brand, like Disney, Louis Vuitton or Christian Dior. To divine the future of my brand, it may be helpful to imagine the evolution of artificial intelligence and what lies beyond. In that future, perhaps I would instruct the AI, “I want this part to be brighter,” or “make this color more chic, no, more colorful!” and the AI would analyze all my past works and calculate the most appropriate mode for the Murakami brand.

Of course, such predictability would quickly become boring, so I intend to push forward with creativity that would upend any calculable future.

“Murakami vs. Murakami” will be on show at the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts until September 1, 2019.

See more from Takashi Murakami’s guest editorship here.

Video by CNN’s Stephy Chung, Momo Moussa, Tom Booth, Oscar Holland and Stella Ko.