Editor’s Note: Stephen Bayley is an acclaimed British author and founding director of the Design Museum in London. The following is an extract from his book ‘Taste: The Secret Meaning of Things’.

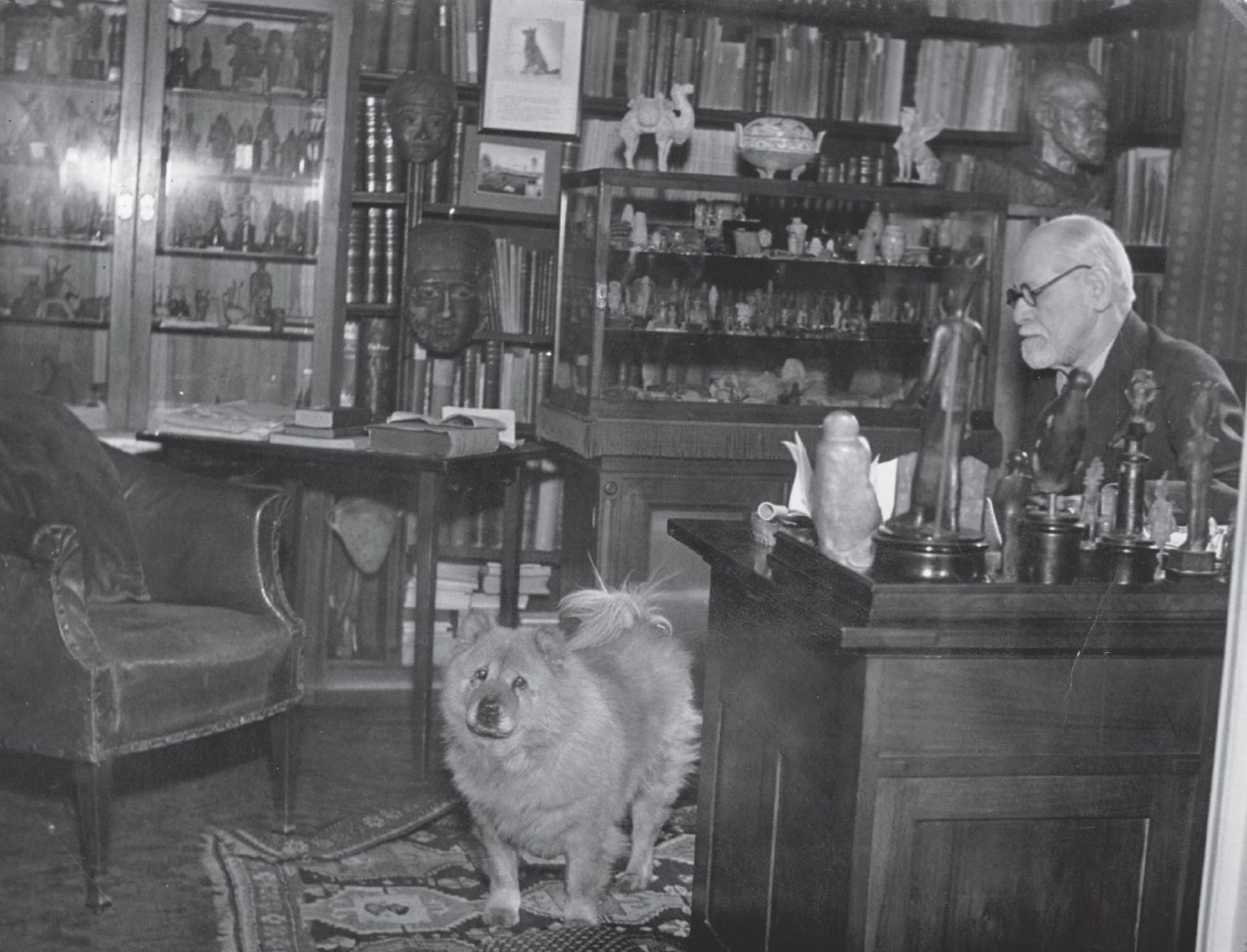

Look above at Dr Freud’s consulting room. The great man is sitting in a sombre Viennese interior, no doubt pleased with the popular reception of The Interpretation of Dreams. You can see the craquelure, smell the leather and the polish, sense the aspidistra, sniff the dust.

Even though it is a black and white photograph, you can tell the dominant color is brown. Tomes of grim, scholarly Mitteilungen suggest that psychoanalysis has the sanction of the past, that it is an ancient and respected academic medical practice.

Several things would be different if Dr Freud were practicing in New York or London today rather than in the volatile Vienna of Loos, Schiele, Klimt and Werfel.

One is that his consulting rooms would not look the same: nowadays leaders of the medical profession do not present their seriousness in terms of sombre bourgeois interior design. Instead, wealthy medical professionalism is suggested by black leather and chrome furniture, middlebrow junk art and glass tables piled high with photo monographs next to the water-cooler.

The other is that the dark corners of patients’ minds would, on inspection, be found to be corroded not by Freud’s own anxieties about sex, death and mother (for nowadays these things are commonplace), but by … taste. This word, which formerly signified no more than “discrimination,” was hijacked and its meaning inflated by an influential elite who use the expression ‘good taste’ simply to validate their personal aesthetic preferences while demonstrating their vulgar presumption of social and cultural superiority.

Is there such a thing as 'good taste'?

The very idea of good taste is insidious. While I stop short of believing that all human affairs are no more than a jungle of ethical and cultural relativity, the suggestion that the infinite variety and vast sweep of the mind should be limited by some polite mechanism of “good form” is absurd.

Everyone has taste, yet it is more of a taboo than sex or money. The reason for this is simple: claims about your attitudes to or achievements in the carnal and financial arenas can be disputed only by your lover and your financial advisers, whereas by making statements about your taste you expose body and soul to terrible public scrutiny. Taste is a merciless betrayer of social and cultural attitudes. Thus, while anybody will tell you as much as (and perhaps more than) you want to know about their triumphs in bed and at the bank, it is taste that gets people’s nerves tingling.

Nancy Mitford noted in her acute discussion of the term “common” (as in “He’s a common little man”) that it is common even to use the word “common,” which gives double-bluffers rich hunting grounds among the maladroit and insecure. Explicit social class, explicit material taste, social competition and cultural modelling are part of the post-industrial re-ordering of the world and as Nick Furbank wittily pointed out in his book about snobbery, Unholy Pleasures (1985), “in classing someone socially, one is simultaneously classing oneself”. He might just as easily have said “in criticizing someone else’s taste, one is simultaneously criticizing oneself”.

The one certain thing about taste is that it changes.

Taste began to be an issue when we lost the feeling for intelligible natural beauty possessed by the Neoplatonists and medieval artists and writers. Nature and art are, in a sense, opposites, and art has been the most reliable barometer of attitudes to beauty. As Andre Malraux noted at the end of the 1940s, in the modern world, art, even religious art of the past, is divorced from its religious purposes and has become a negotiable commodity for consumption by rich individuals or by museums.

Art was the first ‘designer’ merchandise and there is no surer demonstration of fluctuating taste than the reputations of the great artists and the pictures they created. Averaged across centuries of first lionization and then neglect, it is clear that these reputations have no permanent value: the estimation of the value of art depends as much on the social and cultural conditions of a particular viewer as on qualities embodied in the work itself.

We see in the past what we want to see. Economists call the effects of this “survival bias”, we call it taste. In the sixties Gaudi’s architecture was rediscovered, although it had never really gone away, because it had hallucinatory qualities which the psychedelic generation recognized. In the seventies, “Art Deco” became established as a respectable art-historical label, even though Alfred H. Barr and Philip Johnson had banned it from the new Museum of Modern Art in New York on grounds of it being frivolous and merely decorative.

Sometime, of course, the merely decorative is exactly what’s needed.