Editor’s Note: Christopher Dewolf is a Hong Kong based writer with a focus on architecture and urbanism. He is the author of “Borrowed Spaces: Life Between the Cracks of Modern Hong Kong.”

It rises like a mirage as you pass the fallow fields and fish ponds of outer Hong Kong: a wall of skyscrapers shimmering in the distance. This is Shenzhen, which has grown from a small fishing village into a major financial and technology hub in less than 40 years.

Like many other cities in China, Shenzhen is crazy for skyscrapers.

Of the 128 buildings over 200 meters tall that were completed in the world last year, 70% were in China, according to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH).

Shenzhen was responsible for 11 of them – more than the entire United States, and almost twice as many as any other Chinese city (Chongqing and Guangzhou tied for second place, alongside Goyang in South Korea, with six skyscrapers each).

Tall by design

The city’s relationship with high-rises goes back to 1980, when China’s reformist leader, Deng Xiaoping, declared that a swath of farmland along the Hong Kong border would become a so-called Special Economic Zone.

The decision meant that companies could operate with fewer of the restrictions of a planned economy – China’s first major experiment with free markets since the Communist revolution of 1949. Investors from Hong Kong – and beyond – rushed across the border to build factories and other businesses.

From the beginning, urban planners decided that it would be a city of skyscrapers. Shenzhen’s growing skyline is simply part of its DNA, according to University of Hong Kong architecture professor Juan Du, whose book, “The Making of Shenzhen: A Thousand Years in China’s Instant City,” will be published next year.

The world's tallest buildings

“In Shenzhen, (skyscrapers are) really linked to the image of the city,” she said over the phone. “Between the early 1980s and the early 90s, it had more tall buildings than any Chinese city.

“The term ‘Shenzhen speed’ was coined from the (time of) the construction of the city’s earliest skyscrapers. When Deng Xiaoping made his first visit to Shenzhen, he was really excited by the speed at which tall buildings were being built.”

Today, Shenzhen has evolved beyond its manufacturing roots to become a hub for service industries – especially technology and design. Often described as “China’s Silicon Valley,” the city is home to huge companies like Tencent (which itself built two skyscrapers) and a network of thousands of smaller firms.

But Shenzhen’s geography plays a part, too: the city center is located in a narrow strip between mountains and the Hong Kong border. A growing network of subway lines and a new high-speed rail connection to Hong Kong have made this strip even more desirable, pushing development up rather than out.

Cities in slowdown

Shenzhen appears to be showing no signs of slowing. In addition to a current crop of 49 buildings taller than 200 meters, a further 48 skyscrapers are under construction, according to CTBUH data.

But as Shenzhen grows skywards, empty office space in other big cities has led market analysts to speculate that China is caught in a spiral of overbuilding. The office vacancy rate in Beijing, which stood at 8% at the end of 2016, is forecast to rise to 13% by the end of 2019, according to a report by property firm Colliers International. The report noted that “the growing office supply will still outstrip the growth in demand.”

In Shanghai, the country’s tallest building, the 632-meter Shanghai Tower, has sat largely empty since opening in 2015, with one of the project’s lead developers, Gu Jianping, admitting at an awards ceremony last year that “the biggest challenge facing China is how to build fewer skyscrapers.”

Across China, the race upwards has produced outsized landmarks (like Nanjing’s Zifeng Tower which is nearly twice the height of the city’s next-tallest building) in areas where there was not enough demand to justify construction. Entire new cities were built in places like Ordos, a dusty outpost in the Gobi Desert, which then sat empty for years. Tianjin built no fewer than three central business districts filled with skyscrapers – including one unashamedly modeled on Manhattan.

Some media reports have pointed to the so-called “Skyscraper Index,” an idea first proposed by economist Andrew Lawrence in 1999, which suggests that a surge of investment in skyscrapers is a harbinger of recession.

Bucking the trend

But rather than signaling a downturn, Shenzhen’s spate of new skyscrapers may simply reflect its booming economy. With the highest per capita GDP of any major city in China, Shenzhen is also experiencing soaring land prices.

Last year, the city’s property market was named the mainland’s most expensive, with homes selling for an average of $6,500 per square meter, according to SouFun, which tracks house prices in 100 Chinese cities. There has been a similar trend in the office market, according to David Ji, the head of research for Greater China at property consultancy Knight Frank.

“Shenzhen has a lot of demand for Grade A office space, unlike some other mainland cities that just go for height to compete with each other,” he said over the phone.

And aside from the 600-meter Ping An Financial Centre, which became the world’s fourth tallest building when it opened last year, Ji said that “buildings built in Shenzhen tend not to be that tall relative to Shanghai or other cities.”

In other words, Shenzhen may be building plenty of skyscrapers, but most of them aren’t showstoppers.

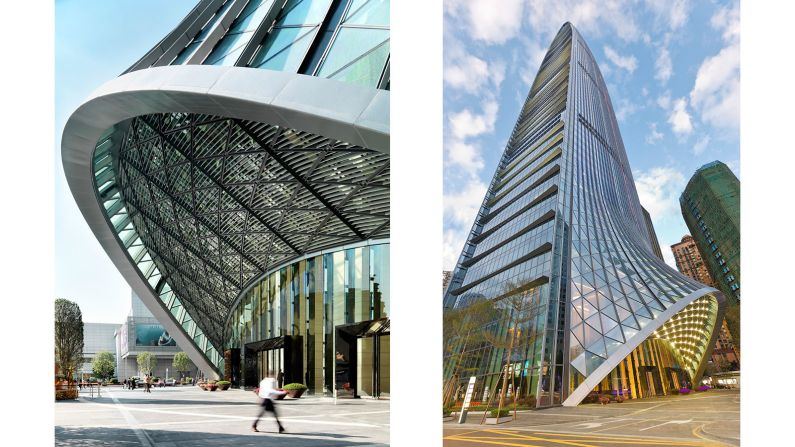

Rather than tolerating vanity projects, urban planners encourage projects that fit in with the surrounding city, according to Hong Kong-based architect Stefan Krummeck. His firm, TFP Farrells, designed KK100, a 442-meter tower that is currently the second tallest in Shenzhen. Rather than an isolated landmark, the skyscraper is part of a former village that was redeveloped in conjunction with KK100.

“There’s always a bit of an ego trip involved in super high-rises, but in Shenzhen it’s more sustainable – the towers are reasonably modest,” he said over the phone. “There are only a few super-high-rise towers and they’re pretty well integrated into the urban fabric.

“To the best of my knowledge, the towers are full and the streets are lively. It works quite well.”