Most collectors begin with an obsession for a particular object of lust. Sometimes it’s a priceless treasure, like some rare works of art. Other times it’s everyday objects – even ones as overlooked as barbie dolls or coffee cups.

Born into a superabundance of riches, the modern-day Rothschilds’ story is inevitably different. Lord Jacob Rothschild, heir to the family’s English branch, says his collecting habit is driven by the desire to acquire the rare things that are “missing.”

Waddesdon Manor, the English Rothschilds’ ancestral palace in rural Buckinghamshire, is a fortified castle overflowing with the type of Versailles-inspired, gilded extravagance that became known in the late 19th century as “le goût Rothschild” (or “the Rothschild taste”).

Inside, the full, eclectic range of objects amassed by Jacob Rothschild’s ancestors – once unrivaled as the world’s richest family, and today possessors of an unknown fortune – become clear.

History's riches: Inside the Rothschild collection

There is a writing desk made for Marie Antoinette, a gold bracelet bearing Queen Victoria’s face (a gift from the Queen herself) and an assortment of 25,000 antiques and artworks, including a clockwork automaton showing an elephant hunting party and a painted screen depicting monkeys dressed in 18th-century gowns.

Then there’s the aviary of rare Asian songbirds – including species named after Rothschild’s ancestors – that form a living collection in the manor’s grounds.

Such vast wealth offers “a wonderful opportunity,” says the 83-year-old investment banker now responsible for the collection – one of a steady stream of striking understatements he gives during an interview in Waddesdon’s crimson smoking room. “Here I am living in a house with these great works of art. There are, of course, some gaps in the collection. And it’s of great interest to me – and great fun – closing those gaps.”

Set amid a 4,000-acre estate, Waddesdon was built as a weekend retreat to accommodate its original owner’s twin passions: weekend partying and collecting valuables. The two were linked, explained Jo Fells, head of communications at Waddesdon. After all, she said, there are few things wealthy Victorians liked more – after some feasting and drinking – than brisk strolls, browsing art and writing letters “to tell everyone how good a time they were having”.

Designed by French architect Gabriel-Hippolyte Destailleur for Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild in the 1870s, Waddesdon is itself a greatest hits compilation of architectural styles.

A neo-renaissance reinvention of a 16th-century fairytale chateau, the building was extended mid-construction to add an addition of a wing for art and leisure: “Destailleur put the idea to (Baron Ferdinand) that the house should incorporate the best features of the best chateaux of the Loire,” Rothschild says of the manor, which has since appeared in period dramas including “Downton Abbey” and “The Crown.”

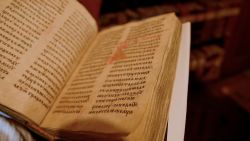

Walking between the house’s dim-lit rooms, Rothschild says that the collection was already built as he was growing up: a diverse assemblage, with strengths in French 18th-century furniture, ornate porcelain from the royal factory at Sevres and illustrated medieval manuscripts.

Over the years, much of the collection has been donated to the British Museum or the National Trust, a conservation charity that was bequeathed the building by Jacob’s relative, James de Rothschild, when he died in 1957. But thousands of items remain in the family’s personal collection.

The desk that once belonged to Marie Antoinette, the infamously decadent last Queen of France who was guillotined during the French Revolution, is “one of the great treasures of the house” and a “perfect example” of what his ancestors wanted, says Rothschild.

“The dream of a Rothschild collection of the 19th century would have been… the queen’s desk,” says Rothschild, produced by “one of the greatest French cabinet makers of the day.”

For the uninitiated, any “gaps” or “holes” in this collection might be hard to identify in rooms with barely a wall or corner to spare (a busy style that is often favored by this type of 19th-century manor). But Rothschild says he is always looking to develop to the collection’s unique character and find complementary works.

Rothschild points to an oil painting of a boy delicately arranging a house of cards. This is one of his own acquisitions, a painting by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, an 18th-century French painter famous for his masterful still-lifes and softly-lit portraits of everyday scenes. Rothschild’s ancestor, Henri, once owned 18 of Chardin’s works, though they were all destroyed in a bombing during World War II.

The painting of the boy was offered to Rothschild by an art dealer, and apparently similar “random opportunistic examples” often present themselves to the family.

“If you look around this room, you’ll see an extremely interesting silver cup by the Dutch 17th-century artist called Van Vianen,” Rothschild says during a tour of the house. “Suddenly a dealer rang me out of the blue… and said, ‘I found a picture of the silver artist’s son holding the cup. He was acting as his father’s salesman. You ought to buy it’.

“So we did buy it,” he said of the cup, which now stands next to the painting of the same cup in Waddesdon’s treasure room.

Other objects have come to Rothschild via the British government thanks to a committee that stops certain cultural artifacts from leaving the country. When temporary export bans are placed on artworks deemed to be national treasures, in the hope that a UK-based buyer can be found, Rothschild has been known to step in.

There are plenty of more carefully curated acquisitions too – especially in the manor’s expansive collection of contemporary art. Jacob Rothschild has added paintings (portraits of himself, specifically) by his friends Lucian Freud and David Hockney. He has also commissioned a chandelier of smashed porcelain by German designer Ingo Maurer and two giant “candlestick” sculptures by Portuguese artist Joana Vasconcelos, constructed from bottles of Château Lafite Rothschild wine.

There is plenty of wine around. Waddesdon’s cellars, containing another sizeable collection: 15,000 bottles of historic wines from the family’s estates, Château Lafite Rothschild and Château Mouton Rothschild. Dating back to 1868, it’s the largest collection of Rothschild wines anywhere in the world.

It is perhaps unsurprising that there are so many Rothschild collections around. Not only is this a family with over two centuries of dizzying wealth, its one whose story begins with a collector: patriarch Mayer Amschel Rothschild, who launched the family’s expansion into finance was, among other things, a dealer in coins, medals and jewels.

From humble beginnings (“in the Ghetto, in Frankfurt, and they lived in a room, 18 of them,” as Rothschild characterizes it), the family has done more than almost any other to amass collections of valuable artworks, public and private, around the world.

Amid the 25,000 works of art at Waddesdon, Jacob Rothschild appears something like a collector of collections, completing what is left to him and amassing countless new additions.

He’s unable to even guess the items’ combined value. Is there, though, one favored piece among the lot?

“Obviously I have particular works of art that I love in this place,” he replies. “But I don’t think there is a particular object… (that) I go back to again and again and again.

“I think I enjoy the luxury of being able to see the range of works of art we have here, and enjoying them all and learning from them in very different ways.”