Editor’s Note: Take a virtual tour of the RIBA International Prize shortlist here.

Story highlights

The winner of the inaugural RIBA International Prize has been announced

This prestigious international architecture award has gone to the "most significant and inspirational building of the year," according to RIBA

The Universidad de Ingeniería y Tecnología (UTEC) in Lima, Peru has won the first ever RIBA International Prize. The building has been selected by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) grand jury, from a shortlist of six vastly different structures scattered across the globe, as the winner of the inaugural award.

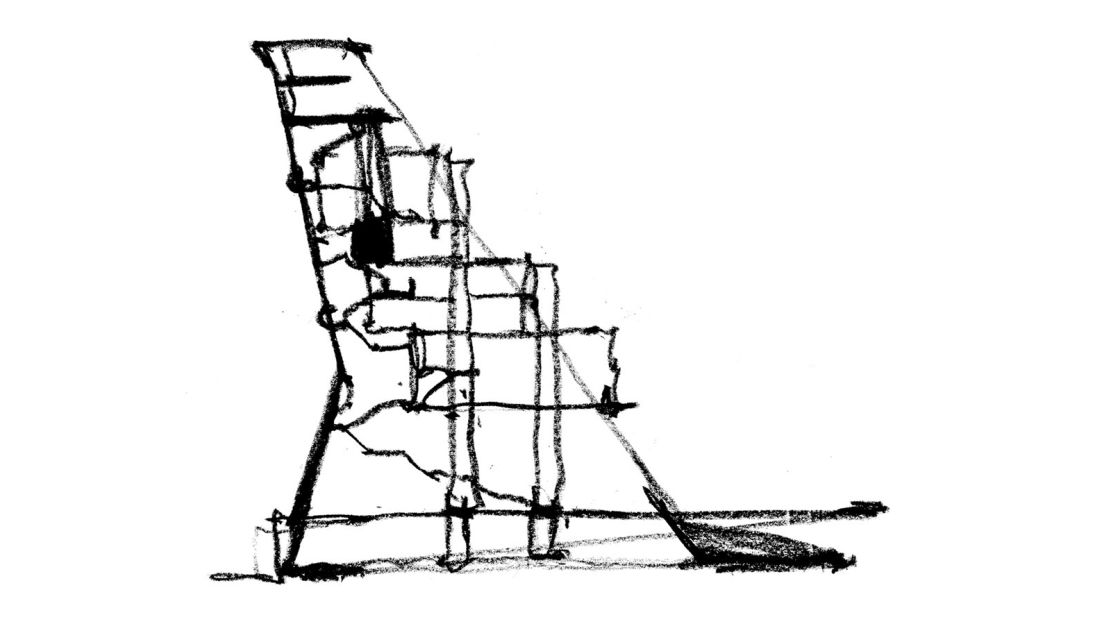

“This is architecture as geology and geography,” says Yvonne Farrell of Grafton Architects, the practice behind the winning building.

“It’s an artificial cliff face hollowed out as if from solid concrete. It’s a challenging building. Its beauty isn’t skin deep. It’s not a pretty package with a fancy ribbon around it. It’s a framework for life that shakes beauty up a little.”

A prize for architecture, not architects

This powerful first building for the new Peruvian university certainly goes against the grain of conventional beauty, and against the kind of “Hey! Look at me!” architecture we have learned to expect from the most celebrated 21st-century architects. But as Richard Rogers, chairman of the RIBA International Prize jury, is at pains to stress, “this is a prize for a building, not an architect.”

What a building must do is to work well for those who use it and for the city it belongs to. Flanked by roaring urban motorways, this concrete megastructure, designed by Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara and their team in Dublin – in collaboration with local partners Shell Arquitectos – is truly a part of the Lima landscape.

VIRTUAL TOUR: Explore each of the shortlisted buildings in 360 degrees

How so? The city is framed and shaped by a wall of towering vertical cliffs dropping down to the Pacific Ocean, and by a plethora of “huacas,” those monumental stepped shelves ancient and Inca civilizations built here for religious and civic ceremonies.

Not only is the new university building cliff-like, but it also hosts any number of 21st-century huacas of its own: outdoor spaces between teaching blocks and on several levels where students can congregate, or simply stare across to the ocean and to the mountainous landscape beyond the city.

Because Lima’s climate is mild all year round despite its tropical setting – thanks to the cooling influence of the Humboldt Current that laps against its vertiginous shores – the UTEC building boasts as many outdoor as indoor spaces. There is little need for air-conditioning.

If the north face of the building – curving in a boomerang shaped arc along the motorway – is monumental, to baffle noise and shade the interior, its counterpart, the south face, is a thing of cascading terraces that, soon enough, will overflow with brightly colored bougainvillea.

Civic duty

“It’ll be rather like Machu Picchu,” says Philip Gumuchdjian, one of the five architect judges of the RIBA International Prize. “Choosing a winner from six impressive yet very different finalists was always going to be difficult, but we were looking for a design that somehow came from the culture of the site while promising those who use it a fresh way forward in their own lives.”

“It’s had a real impact on the students and faculty,” says Carlos Heeren, UTEC’s CEO. “Its open spaces push their ideas to the limits, its solid structure makes them feel safe to explore and take risks, and its elegant lines remind us that beauty can be found even in concrete.”

The building has attracted government departments, hospitals and other Lima institutions to study and learn from its solid, yet open plan; its powerful yet cosseting form.

This is an inclusive and empowering building. These virtues are evident at every turn through its complex section – the view, that is, through its structure. Here, there are few corridors. Instead, rooms seem perched along walkways, one cantilevered above another. What seems like such an impenetrable architectural outcrop from the motorway proves to be remarkably permeable, almost as if the ocean had carved caves and grottoes through fissures in its apparently invincible facade, and the city itself had seeped inside.

Constructed from a single material – white concrete – the building is far more colorful than might be supposed. Eventually, this will be due in no small part to tropical plants reaching down its south face. Yet even now, spectacular sunsets bring varying color to this concrete cliff of a building. The stuff of meteorological sorcery, summer sunsets here are known as “cielos de brujas” or “witch skies.” Inside the interlocking internal spaces of the building, sunlight and shadows dance the day away.

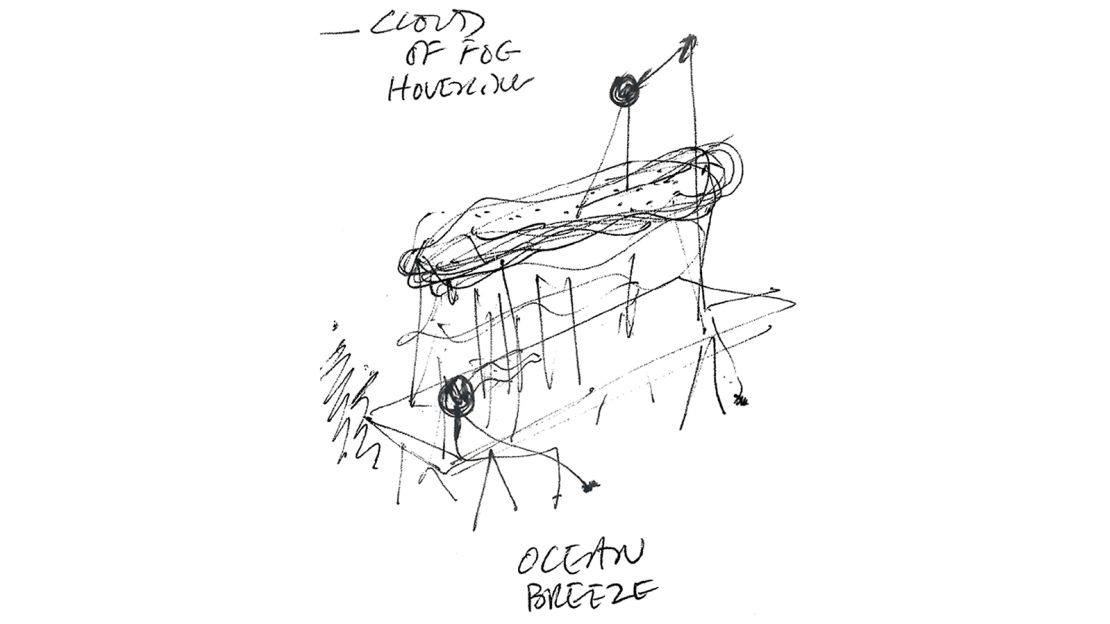

This is very much a building that needs to be experienced if it is to be understood. UTEC is not just architecture for the eyes, but, as Yvonne Farrell says, “for all the senses.” Through much of the building you can feel the ocean breeze, hear the sound of voices echoing through its spaces and experience innumerable shades of daylight. Grafton Architects see UTEC as a building concerned with the totality of architecture.

As Billie Tsien, a distinguished American architect and RIBA juror, puts it: “UTEC is an exploration both in terms of material and, socially, as a work in progress. You have the feeling that it will only improve over time.”

RIBA International Prize: The battle to be the world's best building

Take a virtual tour of the RIBA International Prize shortlist here.