David Bowie released his sixth studio album, “Aladdin Sane,” on April 13, 1973, and the cover portrait of the late British rock star has become one of his most famous images.

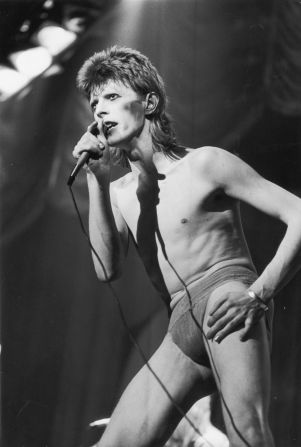

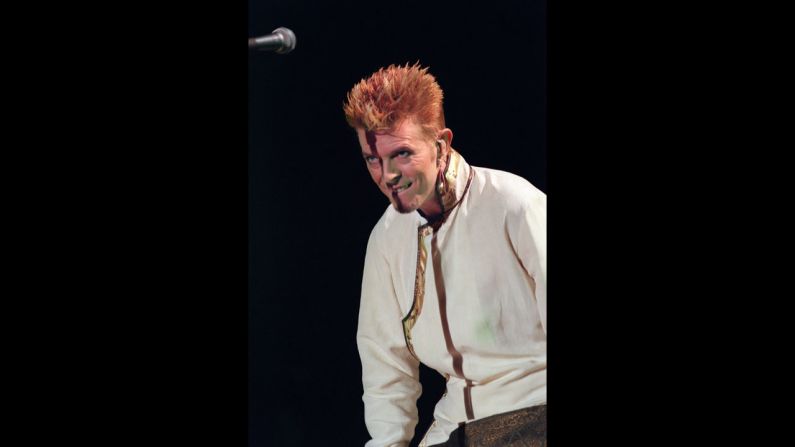

Against his flaming red cropped mullet, Bowie’s skin glowed ghostly white and fuchsia; his bare brow, lids and cheekbones accented to alien effect. A vivid red and blue lightning bolt slashed down his forehead over the right side of his face, his eyes gently closed, his lips parted. Bowie appeared as an androgynous, other-wordly being lost in thought. The musician had already become famous for his gender-defying and theatrical personas, standing out from the tough frontmen of punk rock and metal that emerged that decade.

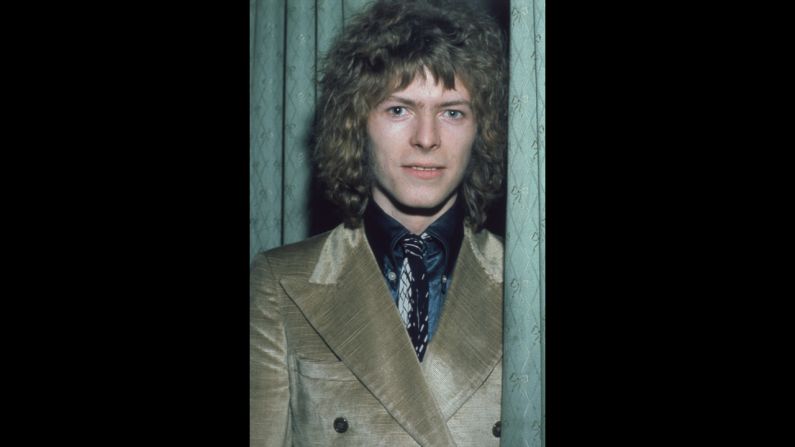

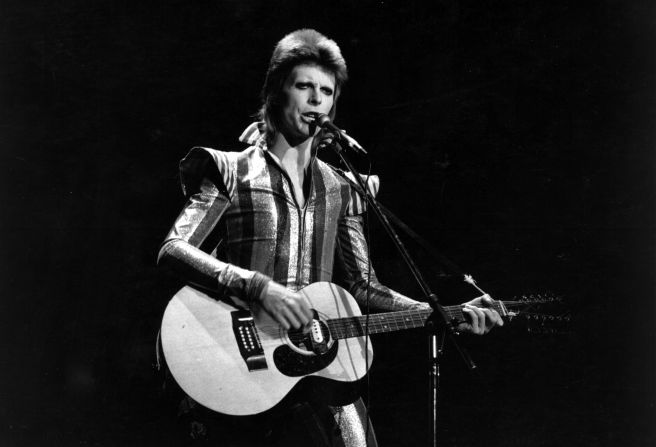

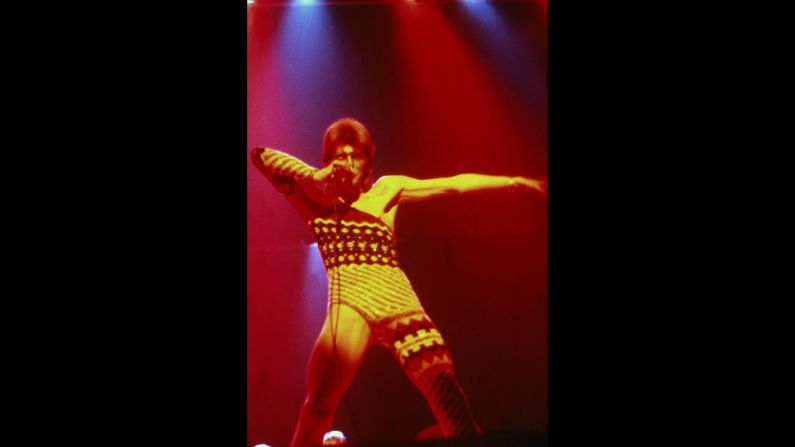

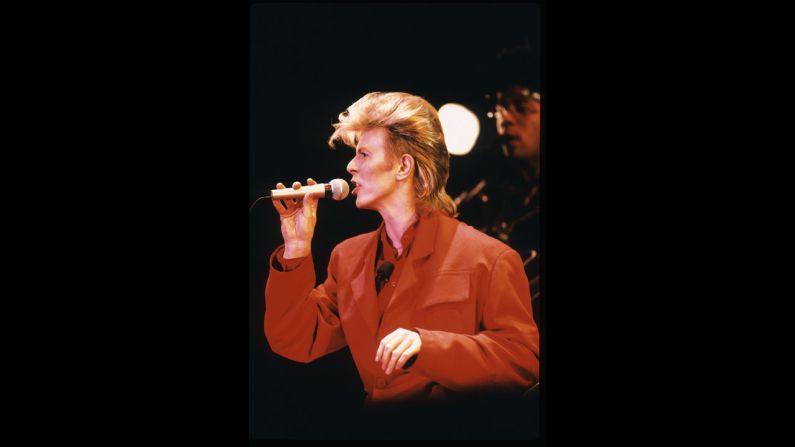

Bowie slipped into his glam alter-egos to enhance the mythology around his music and his performances. For his king-making 1972 album, “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars,” he assumed the form of a hedonistic alien rock star with wide-ranging sexual proclivities who lands on earth during the planet’s final years.

Bowie imagined his next character for “Aladdin Sane” as an “electric boy,” as he explained to Rolling Stone in 1987. “I thought he would probably be cracked by lightning.” With a play on the words “a lad insane,” Bowie mixed the idea of illumination with a bit of the madness of his newfound fame. The character was still reminiscent of Ziggy, which Bowie acknowledged. “(I was) getting out of Ziggy and not really knowing where I was going. It was a little ephemeral, ‘cause it was certainly up in the air.”

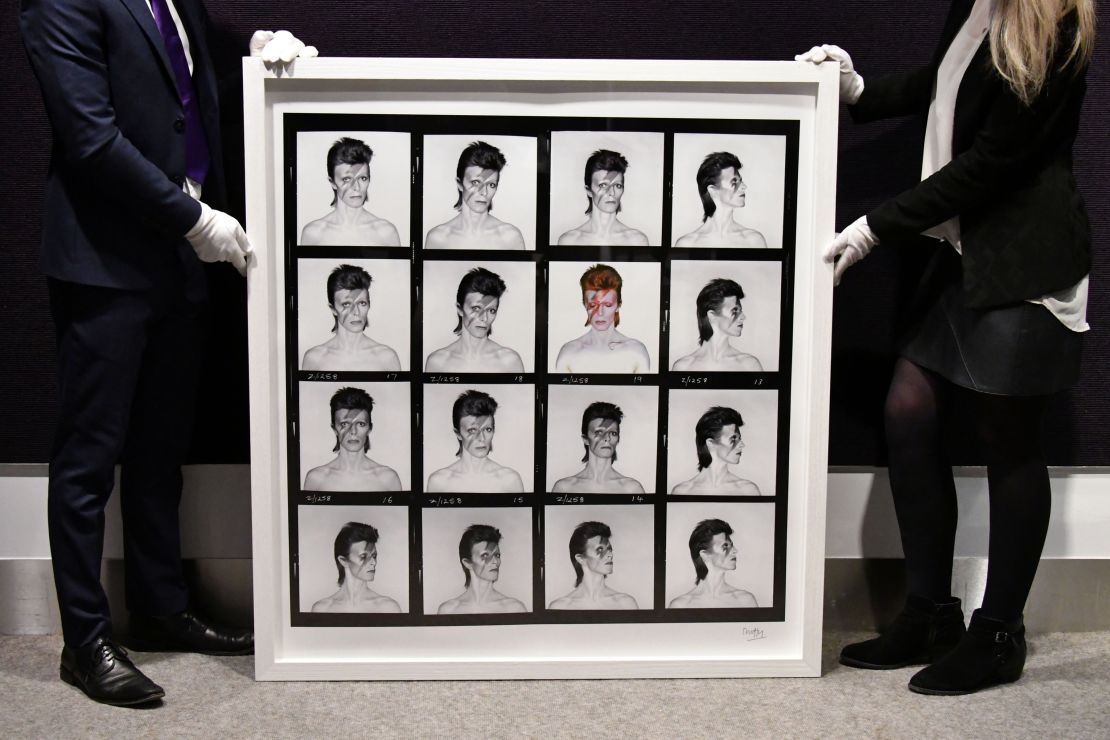

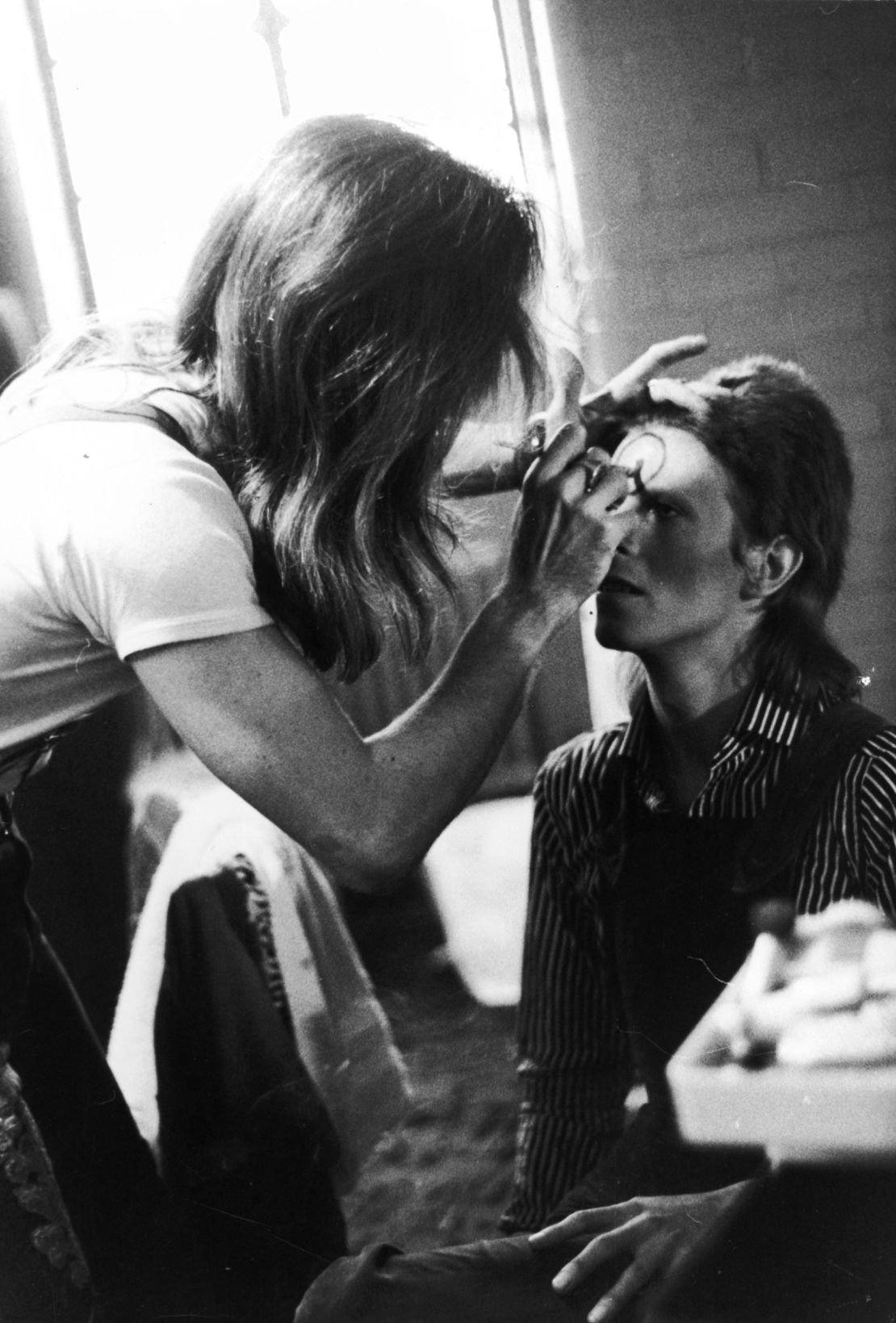

According to Brian Duffy, the photographer who shot the now-iconic cover image image, when Bowie said that he wanted a flash of lightning across his face, Duffy and makeup artist Pierre La Roche copied the bolt from a nearby Panasonic rice cooker in Duffy’s studio.

That graphic element, carefully filled in with lipstick, has become synonymous with the rock legend. From Scandinavian dolls to a constellation of stars near Mars. the lightning bolt has been an enduring symbol.

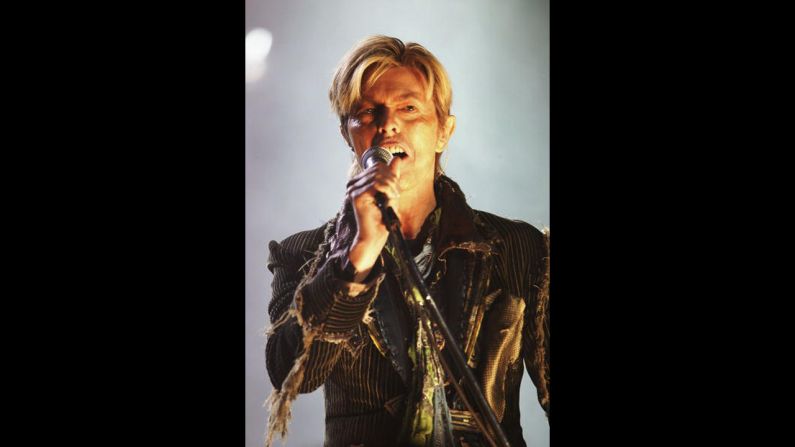

Countless fans have applied their own lightning bolts in homage – today one can find an endless number of tutorials for the flash to channel Bowie’s electric mystique.

In 2003, Kate Moss famously graced the cover of Vogue with the red-and-blue flash overlaid on her face. Ten years later, a print of the Moss photo, taken by Nick Knight, sold at Christie’s for $38k (£30k).More recently, actress Sarah Hyland sported the look for Halloween, while singer Kesha wore it this past January for what would have been Bowie’s 73rd birthday.

Inspired by theater and space operas, Bowie wanted to outdo heavily makeup-ed, larger-than-life rock personalities like Alice Cooper. But instead of shock value, Bowie was more interested in pushing the gender boundaries of accepted beauty and sexuality norms.

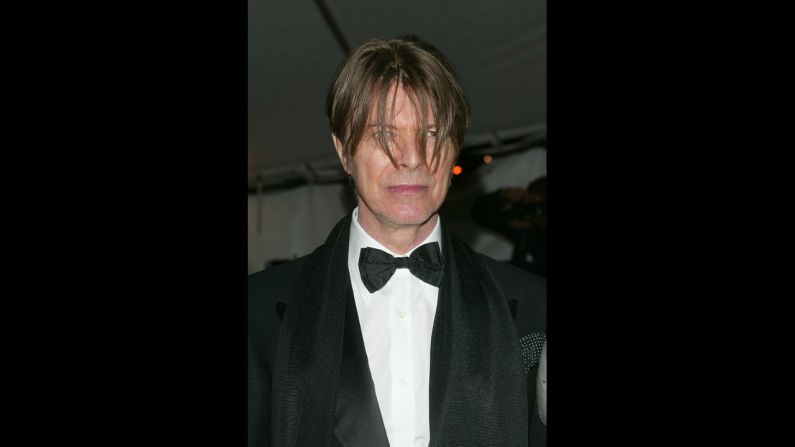

“He spent a lot of time creating these personae that were androgynous – they weren’t from this planet,” cultural critic Wesley Morris told NPR following Bowie’s death from cancer in 2016. “If you were a kid, it was kind of weirdly exciting, because these ideas of gender and masculinity and femininity are these acquired notions.”

Bowie’s lightning bolt became a phenomenon; it was even more recognizable than the gold astral circle he wore on his forehead as Ziggy Stardust, which had propelled him to stardom the year prior (and, which was recreated on a special-edition Barbie released last year to honor the anniversary of the album launch).

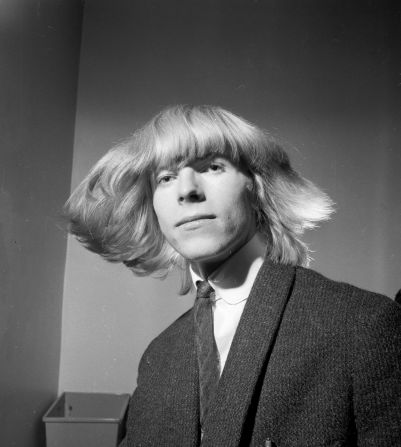

Before he gained an international following, the musician faced backlash for his full makeup looks. “There was quite a bit of antagonism,” he said. “Nothing like, say, the (Sex) Pistols got when they started. But the first couple of months were not easy. The people did find it very hard, until we had a musical breakthrough.”

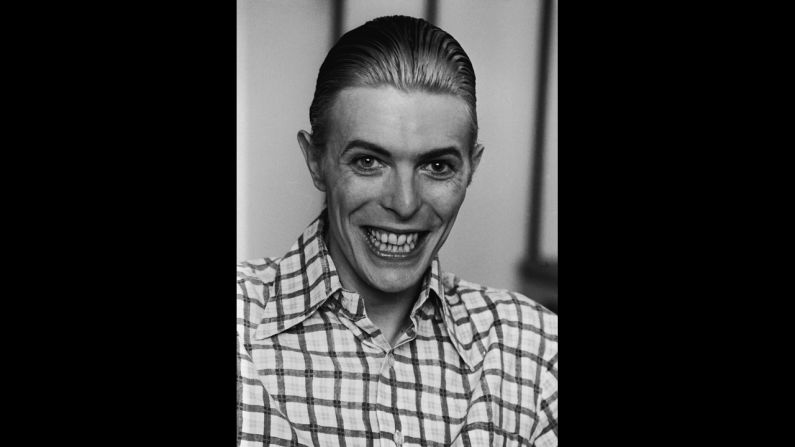

As his international profile grew, Bowie’s eclecticism was more than accepted – his fandom became avid. “At first, I just assumed that character onstage,” Bowie once told Rolling Stone. “Then everybody started to treat me as they treated Ziggy…I became convinced I was a messiah. Very scary. I woke up fairly quickly.”

Bowie wrote “Aladdin Sane” while touring the States. His music took a darker turn, representing his fascination with the sleazy underbelly of American culture. He later called the album “Ziggy under the influence of America.”

Ziggy himself would ultimately meet his demise, killed off onstage three months after the release of “Aladdin Sane.”

“Most rock characters that one creates usually have a short life span,” Bowie explained to Rolling Stone. “I don’t think they’re durable album after album. Don’t want them to get too cartoony.”

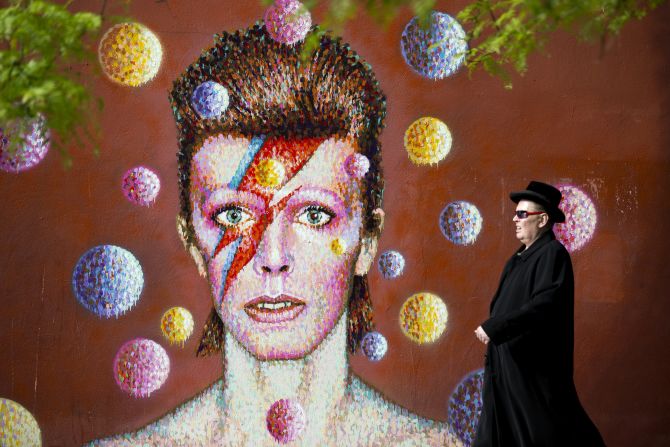

When Bowie passed away, legions of fans began gathering at a mural in his home district of Brixton, south London. Painted by street artist Jimmy C in 2013, it showed the musician in the guise of Aladdin Sane, with celestial bodies orbiting around his head. With hundreds of bouquets and memorabilia soon stacked against the wall, the site became a tribute to Bowie’s life and work.

Bowie’s career was more than just a flash of lightning – it was a supernova lighting up the skies. Yet the flash from “Aladdin Sane” remains a fitting tribute to the electric presence of the Starman.