Editor’s Note: “Nomadland” won best picture, Chloé Zhao best director, and Frances McDormand best actress at the 93rd Academy Awards on April 25. This feature, published ahead of the awards, asked the cast and crew to reflect on the production of a history-making Oscar winner.

Having been wrenched from the earth, the mineral gypsum is crushed first. It’s then blasted at high temperatures and ground down, packed up and shipped out to find a new purpose. What’s left behind is a void; an empty space where something once thought permanent used to be.

Such was the fate of Empire, a mining town near the Black Rock Desert, Nevada. When the gypsum mine closed in 2011 under the weight of the recession, it extinguished the community and scattered its people. Not even the zip code survived.

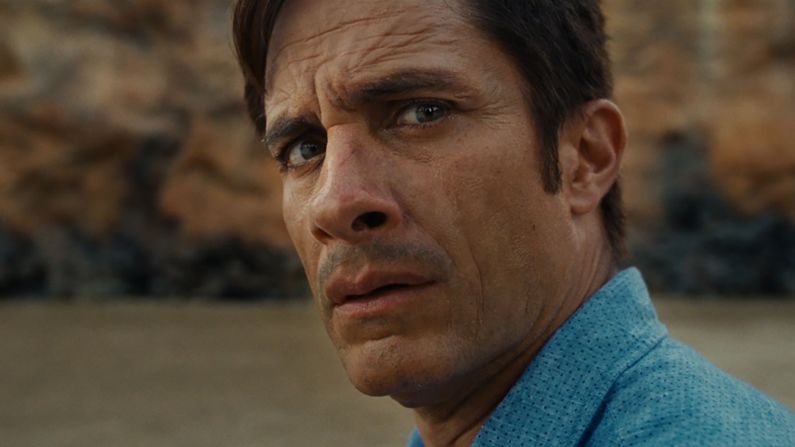

Out of this event the character of Fern was born, the lynchpin of Chloé Zhao’s Oscar-frontrunner “Nomadland.” Played by Frances McDormand, Fern is a widow who leaves Empire to become a nomad and travel the American West. Amid its vast landscapes she finds a new purpose with people brought together by happenstance and bonded by the road.

Fern is a fiction, but the world she inhabits is not. The itinerant lifestyle of a subsection of the baby boomer generation is becoming well-documented – through Jessica Bruder’s 2017 non-fiction book “Nomadland: Surviving America in the 21st Century,” from which “Nomadland” was adapted, but also Zhao’s film.

The director’s novel approach, enlisting two-time Oscar winner McDormand to act as a friend and confidant to real life nomads playing themselves, has become one of the film’s most beguiling features, if not its defining one. These interactions, like everything in “Nomadland,” appear effortless. But the film’s grace was hard won; the product of a dedicated crew who found poetry out west and presented it to audiences with rare clarity.

Winner of a slew of awards, the film has been nominated for six Academy Awards: best director, best adapted screenplay and best editing for Zhao, best actress for McDormand, best cinematography for Joshua James Richards, and best picture. But how “Nomadland” was made is every bit as noteworthy as the film itself.

CNN spoke to Zhao, her cast and her crew, and asked them to recall the long journey to screen. The following interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

The story begins in 2017 when McDormand and producing partner Peter Spears optioned the rights to Bruder’s book. In 2018 McDormand pitched the film and the directing job to Zhao, whose second feature “The Rider” had impressed the actor.

Joshua James Richards, cinematographer/production designer: Chloé had been looking at alternative ways of living on the road for years, so there was an element of serendipity when Frances McDormand came with this project.

I read the book the same time as Chloé (Richards is Zhao’s partner as well as regular cinematographer) and there were some early discussions about the potential for narrative – because it was unusual to take a documentary book and turn it into narrative. But we immediately saw this middle ground and that excited us.

Zhao spent time with the film’s two professional actors, McDormand and David Strathairn, developing their characters, but she also needed to cast the nomads. She and Richards embarked on a road trip in their campervan “Akira” to connect with the community, including Swankie and Linda May, who featured in Bruder’s book and would go on to star in the film.

Linda May, actor/nomad: Chloé came to visit me in Douglas, Arizona. I happened to have several van-dwelling RV ladies in my neighborhood at the time, and Chloé asked if we could all get together. We just told her stories all day.

Swankie, actor/nomad: They caught up with me in Colorado. I thought it was neat that they actually had a camper van and they were building it out. That sort of surprised me. They cared about the lifestyle.

Chloé Zhao, writer/director: The trip gave me time to let go of all these worries about production and just experience the landscape and meet people and not feel like I had to commit to anything.

Richards: It was kind of an on-the-road screen test. The most important thing was familiarizing ourselves with the nomads and getting a sense of how they’re going to be in front of camera.

Swankie: Chloé doesn’t take no for an answer. It took her two days to talk me into it. I had this surgery coming up and I didn’t know if I would still be in a sling when they started shooting. She said, ‘we’ll work around it,’ and I went, ‘wow, they really must want me.’

Richards: Swankie’s monologue (one the film’s highlights in which she describes a moment of bliss in the wild) came from the first time we met her. Chloé was like, ‘please remember that.’

Those trips are not just important, they’re the magic trick. Because the audience arrives once all these relationships have been formed, but all the work is done really in prep.

Zhao: Every project I’ve done, there is this moment in prep which is my own dark night of the soul. I go, ‘Do I have a movie?’ You’ve gathered so much and it’s all in your head and it hasn’t worked yet. That trip really made me realize that it could.

Beginning in South Dakota in September 2018, the 36-strong crew traveled through Nebraska, Nevada, California and Arizona over six months, picking up scenes as they went. McDormand is in nearly every shot, delivering a flinty, unfussy performance typical of the actor.

Zhao: She’s one of the legends.

Richards: She is a force of nature.

Swankie: I’d never heard of Frances McDormand before. But somebody pointed her out and I thought I should introduce myself. I tapped her on the shoulder and started to say, ‘hi I’m …’ and she turned around and squealed ‘Swankie!’ She started talking to me excitedly about all the plans and the scenes. It was like working alongside an equal.

Richards: It was tough on Fran, because the nomads come in and Chloé would have to work with them quite carefully. And then Fran gets five minutes and just kills it. You feel bad, because we’d leave a scene and everyone’s just ‘Swankie! God, Swankie!’ Then, ‘well done, Fran. Anyway, next scene.’

Linda May: The crew was so enthusiastic. I eventually learned they had morning meetings and would go through what the shoot was going to be that day, so Frances knew what they were trying to capture. I wasn’t included in those roundtable meetings – all for the better.

Zhao: With non-professional actors, I do not like to rehearse them. With these wide-angle lenses close to people, the lens is very sensitive to things that are not authentic. So even though the first take might not be usable, sometimes there might be something there that cannot be repeated. And I would really hate myself if that wasn’t on camera.

Swankie: Oh my god that camera was so big, and he got so close to my face. You forget the camera after a while – until you see the movie on IMAX and realize your wrinkles have been multiplied 50 times.

Richards: (No-rehearsal) impacts everything. Gone are the big lighting rigs. You’re allowing as much freedom as possible.

You have me, Wolf (Snyder, production sound recordist) and Chloé all moving as one. If (image, sound and performance) aren’t all working, then there’s no point. Chloé would even look to Wolf sometimes about performance – close your eyes and you can hear a bad performance almost better than you can see it.

Linda May: Chloé would just say, ‘tell me this story,’ or, ‘we’re gonna have this conversation.’ I just got to be myself. Almost everything was done in one take.

The result is documentary-style testimony within a narrative framework. Perhaps the most powerful account is that delivered by Linda May, who describes contemplating suicide in 2008.

Linda May: I wouldn’t say (I was) happy to share my lowest point, but it was honest. I think sometimes our greatest defeat can turn into our biggest strength. To be able to share that with someone who may be considering ‘this is the end of the road for me, there’s nowhere else to go’ – that if you just take one more step, magic and miracles can happen. To put my life on screen like that, another human being can see, ‘wow, one day she was going to kill herself and today she’s a movie star because she didn’t.’

Richards: It doesn’t get any more collaborative and inclusive than the experience of “Nomadland.” I mean, Derek …

Derek Endres was found through street casting; a young man who had been hopping trains and living on the road for four years, says Richards. Zhao says his scene best illustrates her approach to filmmaking.

Zhao: The scene with Fern and Derek is very special to me. I like to make films where there’s something about it that’s slightly off what the rest of the film is about. Fern is reciting a Shakespeare sonnet with a little young drifter – it seems like it has nothing to do with the rest of the film, but it somehow does fit. When the world throws interesting things at you, catch them.

Richards: We just loved this guy and he started staying at the hotel with us. We said, ‘Derek, do you want to be part of the crew?’ Derek became part of the art department and worked on the movie for a good few months and became part of it.

It’s almost like community theatre, what Chloé is going for. (There have been) questions, ‘why isn’t it just a documentary?’ Why would a documentary be more true than what “Nomadland” is?

Zhao: I think we need both facts and fiction. Since the dawn of civilization, we’ve had poetry, fiction, allegories and myths to help us make sense (of the world) in a safe place.

I don’t have the guts to make documentaries. I think it’s incredibly brave to connect with people and be able to say, ‘this is what you’re giving me: yourself.’ I don’t really know if I could form that kind of relationship. Sometimes, I find the best way to convey truth is through poetry.

Zhao edited the film with an international crew, beginning post-production in 2020.

Richards: Post(-production) was fascinating, in that maintaining naturalism is really difficult to do sometimes. Chloé wanted to be true to the colors that are there and not put anything between the audience. There’s no feeling of the digital intermediate (image manipulation processes including color enhancement) whatsoever.

It was interesting with “Nomadland,” because the experience of the film was just nowhere near complete until sound was done.

Zach Seivers, re-recording mixer/supervising sound editor: Chloé’s insistence that the production sound captures the environment exactly as it is – meaning there’s no crowd control, no locking down of sets – really makes for a magical sounding production track.

Sergio Diaz, sound designer/supervising sound editor: For me, the sound was another character. I wasn’t familiar with the sonic richness of the American West. I was very meticulous selecting the most accurate and atmospheric layers to contribute to the story and make it more powerful, emotionally.

Richards: Chloé and I have been really lucky to be able to collaborate with people who believe in the same kind of things we do. I discovered on “Nomadland” how I want to make movies. Until this film, I wasn’t sure. Now I feel like I know.

“Nomadland” premiered at the Venice Film Festival and the Toronto Film Festival on September 11, 2020, winning top prizes at both. It has been garlanded with awards ever since, and lauded by critics. But some opinions matter more than others.

Swankie: The first time I saw it there were seven other women there that I knew. When my scene came on, that close up, I couldn’t watch it. I honest to god just sat there with my fingers in my ears and my eyes covered up.

I had to go back the next day with nobody with me. That was the first time I actually got it – I could understand the movie from the public’s point of view, I think, because I cried. That was pretty amazing. It’s hard to get gracious enough to watch yourself, especially when you think you’re making a fool of yourself.

Linda May: I know some people say, ‘Oh, it’s so depressing.’ But I don’t see that. I hope that the joy comes through. I think that Chloé got it. What more is there?

Editor’s note: Interviews for this feature were conducted before the death of production sound recordist Michael Wolf Snyder was reported on March 6.