With their pleasing colors and playful compositions, Nguan’s images of Singapore portray the city-state as a dreamy wonderland. But this is somewhat at odds with the photographer’s view of his hometown as a high-functioning but sterile place.

So Nguan, who goes by his given name, subverts the city’s reputation by turning his lens on older parts of the city.

“Singapore is clean and efficient but you don’t feel anything when you think of the country,” said Nguan in a phone interview. “Nobody would refer to (it) as beautiful.

“I wanted Singapore to look like an illustrated fairy-tale.”

Since returning from studying filmmaking in the US in 2007, the photographer has been capturing neglected corners of the country, from its hawker centers to pastel-colored spiral staircases.

Using a film camera from the ’90s, Nguan combines documentary techniques with the aesthetics of fashion photography. His dream-like photos have appeared in two reportedly sold-out photo books (“How Loneliness Goes” and “Singapore”), at international photography fairs and even The New Yorker’s Instagram account, which he took over for his country’s National Day in 2016.

Singapore like you've never seen

Ode to the unseen

The towering Marina Bay Sands resort may be Singapore’s most recognizable symbol, but Nguan depicts a different side to the city-state – one that represents the lives of everyday people.

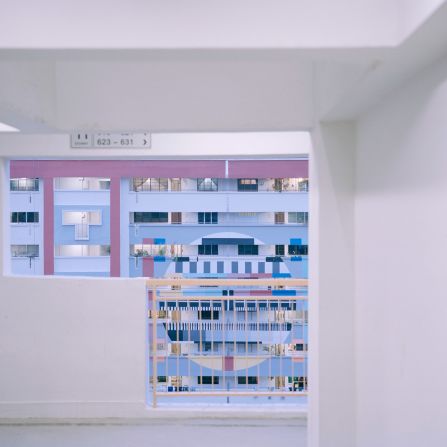

According to government research, over 80% of the country’s population lives in public housing estates. Many of them are found in areas known as the heartlands, satellite towns on the outskirts of the city – places that Nguan’s work largely focuses on.

He is particularly fond of picturing corridors in public housing blocks, as they contain evidence of the complex lives unfolding within, he said.

“Every corridor is like a street on its own,” he explained.

In one photo, a half-naked and barefooted man tends to plants outside a door adorned with Chinese lanterns. Another shows a colorful array of clothes and towels in the corridor soaking up the sunset.

“Many (residents) treat the corridor areas outside their apartments as their own, taking great pride with decorations, placing religious altars on pillars, installing rows of potted plants and drying their undergarments outside,” explained Nguan.

These can all be seen as tiny acts of gentle rebellion, the photographer suggested, as housing regulations often state that residents should keep common areas free of clutter.

“It’s also a distinctly Singaporean trait to carry on with whatever you can get away with,” he added.

“As long as the authorities close one eye.”

Redefining national icons

Nguan sees Singapore as an adolescent nation in a state of inbetweenness. There is, he said, both a longing for the past and concern about the future.

“The rapid development of the city has led to collective nostalgia among Singaporeans because the country they remember is gone (or) going very quickly,” he added.

This unease is embodied by Geylang, a notorious red light district where neon-lit brothels stand amid seafood restaurants and Buddhist temples. Nguan, who often features the neighborhood in his photographs, referred to it as “the final bastion of unruliness in Singapore.”

Yet, this rapidly gentrifying area retains vestiges of the past in the form of shophouses, a style of colonial building found throughout Southeast Asia. The photographer said that, since childhood, he has been “obsessed with” the staircases often found behind the structures.

The ethereal stairways (which were first built to facilitate the night-time removal of human waste), regularly appear in Nguan’s photos. In one striking image, he pictures a row of identical shophouses from behind, their spiral staircases painted in a vibrant mix of blue, green and yellow.

These colorful architectural features face an uncertain future, however. Not all of the staircases are protected by the country’s conservation regulations, and those featured in Nguan’s aforementioned photo might be demolished when the buildings fall into public hands next spring.

Another recurring motif in Nguan’s work is the colorful plastic chairs commonly seen at hawker centers, religious festivals, weddings and funerals. But he also looks to nature, frequently picturing bougainvillea flowers whose bright hue is now known as “Singapore pink.”

“Singapore is a city raised up from jungle and I wanted to show that our true nature cannot be paved,” said the photographer. “I think it’s how we are – we are wondering parts and we are restless by nature.”