Editor’s Note: Does art have the power to bring about real change? Intelligence Squared will explore the topic in an upcoming all artist panel, which will feature Lu Yang, Olafur Eliasson, John Gerrard and Shirazeh Houshiary. CNN Style is the media partner for the event.

Artist Lu Yang is often labeled according to the themes she explores, the digital media she works with or for simply being young and Chinese. But the 33-year-old isn’t interested in categorization.

“I am not a new media artist, nor a post-internet one,” she said in phone interview. “I don’t even understand what ‘post-internet’ means. I am many things.”

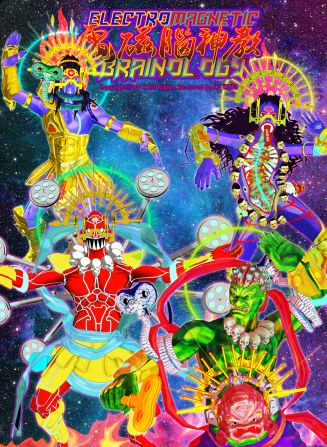

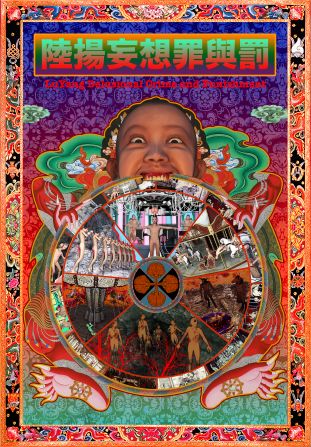

Lu Yang’s art is, indeed, difficult to classify. Her output spans 3D-animated films, video game-like installations, holograms, neon, VR and even software manipulation, often with overt Japanese manga and anime references. Music – electronic and always frenzied – features prominently.

In “Uterus Man” (2013), an ongoing film project, a grotesque superhero rides a chariot made from a human pelvis, eats placenta for strength and skateboards on a winged sanitary pad.

The equally arresting “Moving Gods” (2015), which Lu exhibited at the 2015 Venice Biennale as the youngest of three artists representing China, and “Delusional Mandala” (2015) are both part of a long-term project dealing with science, technology and spirituality – and the taboos surrounding them.

If one were to describe Lu’s work, “intentionally brash” would be a good place to start. Adjectives like bold, loud and boundary-pushing might come a close second.

“I am drawn to many different things,” the Shanghai-born and -based artist said, “and I just like to combine them in the pieces I make, even if they wouldn’t normally be associated with one another. I like the sense of freedom I get from that.”

Exploring the working of the Chinese artist breaking taboos, Lu Yang

Personal, not political

Among Lu’s many fascinations are pop culture – from Japan, especially – eastern religions and philosophy. Gender identity, sexuality, consciousness, neuroscience, death and the human body all feature widely in her acclaimed videos and installations, which have been exhibited in and outside China.

“They are an extension of what defines me as a person,” Lu said of her artworks. “I don’t really separate my work from my private life. Everything I create is for myself. I don’t have any other viewer in mind.

“I don’t have many ‘feelings’ in my everyday life,” she continued. “I don’t cry at sad movies; I am not easily scared. I don’t laugh at stuff other people find funny. So I make strong pieces I can attach myself to, or react to. They are my way of ‘channeling my feelings’ and building my own space out there.”

So while Yang tackles serious issues, she does so in an entirely personal capacity. Breaking taboos in China may often see artists labelled “political,” but Yang is — by her own admission — far from politically engaged.

“A decade ago, politics was what everyone saw when it came to art in China – particularly the West,” she said. “A Western viewer would approach a Chinese artwork and think, ‘Is this an Ai Weiwei-kind of piece?’ ‘Is this trying to be controversial and anti-government?’

“But that’s changed, at least slightly, over the last few years. I think people my generation are aware of politics but also realize that work like mine exists in different dimensions, and for different topics.”

These topics are impressively varied, with Yang’s videos exploring the use of technology and science – stereotactic mapping, transcranial magnetic simulation and VR – while considering its impact on the body and brain. AI is another topic she’s eager to explore. But she rebuffs the suggestion that these concepts are also potentially political.

“I only include technology in my work if it enhances and fits with my ideas,” she said. “But I am not interested in it beyond that.”

Instead, her work is imbued with an unmistakable hedonism. And as she prepares to take part in a panel event in Hong Kong titled, “Art is for pleasure not politics: contemporary art fails to influence political discussion,” it is clear which side of the debate she falls.

“The first part – art is for pleasure – definitely sums up my point of view,” she said. “But that’s just me and my work.”

An online identity

Despite eschewing social media (“I find it very time-consuming”), Yang’s work is defined by her relationship with the Internet. Beside her artworks, it’s the place she feels most at home.

“I like to say I live on the Internet,” she said, “because it’s the only place I feel unburdened from social expectations. I am very active on Vimeo – I post most of my videos on it – and I like that people often discover my work there. It feels liberating.

“The same goes for my interactions. When I chat to people on (Chinese micro-blogging site) Weibo or other platforms, I don’t have to specify whether I am a man or a woman, or what country I am from. I can be anyone I want.”

Having stated in previous interview that she doesn’t identify with being Chinese, Yang feels more affinity with her online identity than her national one. She’s nonetheless aware that she may be considered, a “Chinese artist,” something Yang sees as both a blessing and a curse.

“Everyone’s eyes are still on China, meaning a lot of artists my age can actually do this full-time, unlike other countries, because there’s demand. We’re lucky, in that sense.

“At the same time, you’re still expected to speak out through your work. But I want to just make stuff for myself.”

The Intelligence Squared event “Art is for pleasure not politics. Contemporary art fails to influence political discussion” will be held on March 28, 2018 during Hong Kong Art Basel. Tickets are available here.