Bollywood may be best known for its glamorous casts, glitzy costumes and energetic dance routines. But it also has a far less flattering reputation – for promoting the offensive practice of brownface.

“It’s actually racism,” said award-winning film director Neeraj Ghaywan. “Let’s not mince our words.”

In the United States, the concepts of blackface and brownface date back to the 19th century, when white performers would darken their faces with makeup, and use racist stereotypes to portray black and other ethnic minority characters. White performers did this in a time when non-white professionals were themselves barred from employment in the industry.

And the practice dates back even further in England, to the Elizabethan era, when directors traditionally cast white actors to play minority characters in Shakespearean plays. Even into recent decades, the African general in “Othello” has long been played by a white actor with darkened skin, including Orson Welles in 1951 and Laurence Olivier in 1965.

It’s also appeared in modern films. Dan Aykroyd wore blackface and dreadlocks in 1983’s “Trading Places,” and Robert Downey Jr. appeared several shades darker in 2008’s “Tropic Thunder,” to play a white Australian method actor who darkened his skin to play a black man in a Vietnam war film.

Bollywood has adopted brownface in a number of films – by temporarily darkening the skin of performers, especially when they are portraying characters from disadvantaged backgrounds.

As in the early days of Hollywood, critics of this practice say that Bollywood often prefers this approach to actually hiring performers who have naturally darker skin, thus perpetuating discrimination and inequality in the industry.

For example, the popular 2019 film “Bala” featured the story of a woman who suffered discrimination on the basis of her skin tone.

The woman was played by famed actress Bhumi Pednekar (pictured above), who had her skin darkened in order to play the role. The move was slammed by some Indian media outlets, commentators and on social media.

Some pointed out the irony of one of the film’s promotional posters tweeted by Pednekar, where her character was “surrounded by skin lightening products (and) is actually lightskinned and in brownface.”

Pednekar defended the director’s decision to cast her in the movie, according to Indian media reports, saying factors apart from physical appearance play a major role: “If a filmmaker has taken me, it is because I add some value to the film.”

The director, Amar Kaushik, told the Press Trust of India he “thought about casting a dark-skinned actor,” but “felt Bhumi was superb for this character.”

CNN reached out to Pednekar via her agent and Kaushik for comment, but both declined to comment.

The popularity of films that use brownface, such as box office hits “Super 30” and “Gully Boy,” also released in 2019, suggest that Bollywood is yet to come under significant public pressure for a practice that many people consider racist and offensive.

‘Glamour behind the mask’

India’s attitude towards fairness is an ancient concept.

“It predates colonialism and is certainly linked to caste,” said sociologist Sanjay Srivastava, who works at the Institute of Economic Growth in Delhi.

“Hindu religious texts are full of what we would now recognize as racial stereotypes: lower caste figures as dark and ugly… To be dark is to be a manual laborer, working in the sun. Fair skin is also a mark of class.”

The arrival of pale-skinned British colonial leaders in the 18th century also had a role to play, deepening the prejudice, he said.

“During the colonial era, race and racism functioned in the context of the so-called mixed-race populations, the Anglo-Indians. The ‘closer’ you were to a white progenitor, the higher up in the hierarchy of race.” British rule is also blamed for further polarizing the castes.

Fairness, on the other hand, is revered and considered a sign of beauty and status. “Bollywood, and Indian cinema generally, had two remarkable antecedents: religious iconography and Parsi theater,” said Vijay Mishra, a Professor of English Literature at Australia’s Murdoch University and the author of “Bollywood cinema: Temples of desire.”

“For both, ‘whiteness’ was essential,” Mishra said.

Hindu gods and goddesses are “remarkably white,” except for dark-skinned Shiva, Rama and Krishna, he said. In Parsi theater, “Parsis, through their Iranian ethnicity, are extremely fair.”

Before Hindi sound films were established in India in 1931, Parsi theater, influenced by colonial English theater, served as entertainment for the growing middle and working classes and was hugely popular.

India’s independence in 1947 paved the way for a new constitution that outlawed caste-based discrimination, but it is still prevalent in parts of India. In its 2019 World Report, Human Rights Watch noted that Dalits, formerly referred to as “untouchables,” “continued to be discriminated against in education and in jobs.”

And colorism, discrimination based on the color of someone’s skin, is prevalent in Bollywood, Srivastava argued.

“Colorism is not problematized at all, since a vast number of Bollywood cinema relies upon prejudice as a vehicle for entertainment.

“It would be considered perfectly natural that they would don brownface to portray a dark character… (because audiences) also like to be assured that the glamour is still there, behind the mask.”

While accurate box office figures are difficult to obtain in India, “Gully Boy,” “Bala” and “Super 30” were reportedly among the 25 highest-grossing Bollywood movies last year. All three used brownface.

CNN reached out to Yash Raj Films that handles “Gully Boy” actor Ranveer Singh’s publicity for comment, but they declined.

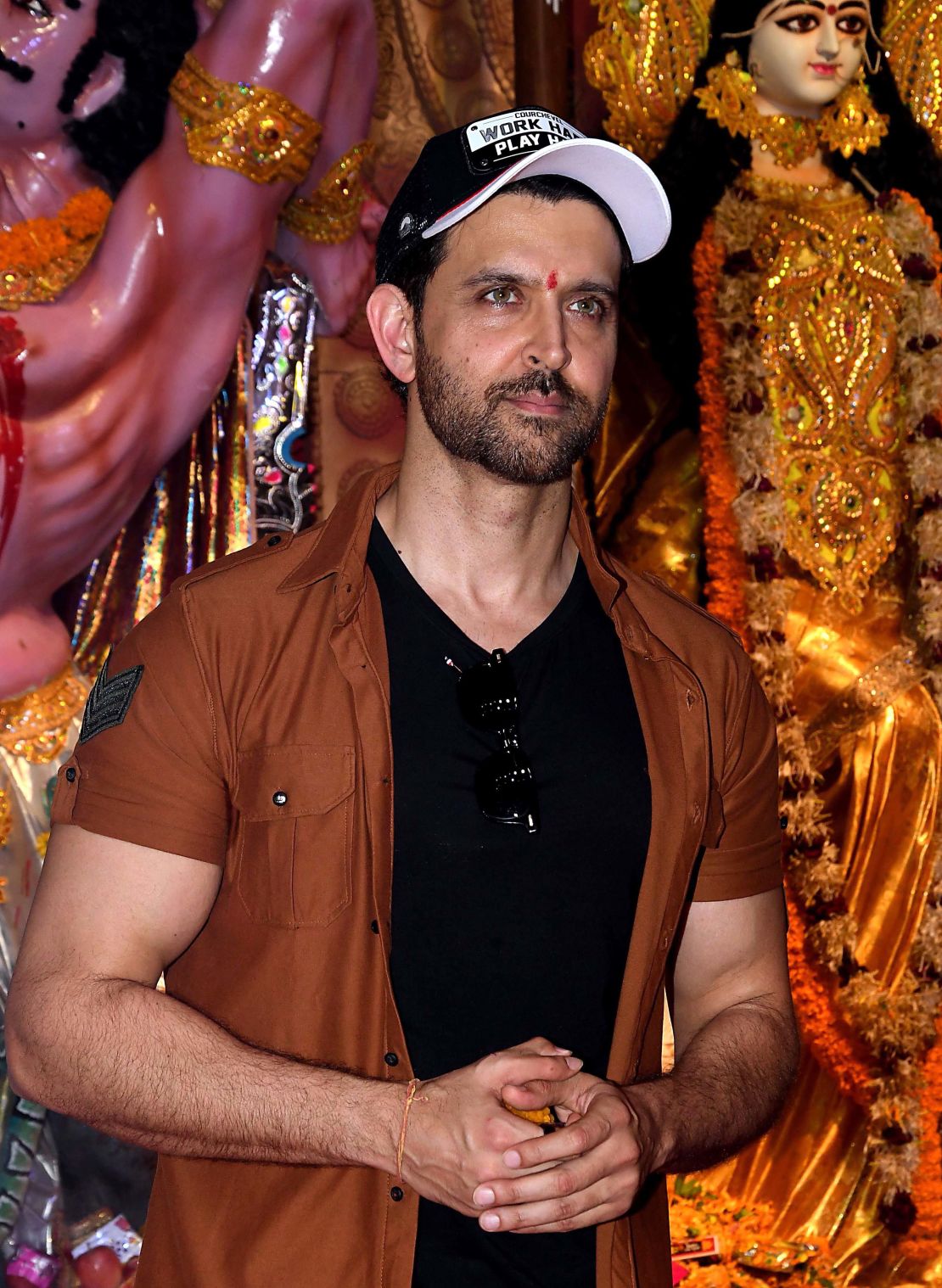

“Super 30” actor Hrithik Roshan’s representatives did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.

The decision to choose a fair-skinned, famous actor over a dark-skinned performer is based on the desire to make a big budget movie “financially viable,” said film director Neeraj Ghaywan, who has worked on Bollywood and independent films. “That is how people think in Bollywood.”

As a member of the Scheduled (or Dalit) Caste, the lowest rung on India’s societal ladder, Ghaywan is a rare exception in an industry dominated by higher castes.

He tweeted a callout last year for assistant writers and directors from lower castes to contact him for work.

Ghaywan believes Bollywood’s lack of diversity may be partly why caste is misrepresented.

People from the Scheduled Caste make up 16.6% of the Indian population, according to 2011 census figures. But in 2014, analysis by The Hindu newspaper found that only two Bollywood movies made that year had featured a lower caste character in a leading role.

However, Ghaywan argued that the root of the problem is that caste discrimination is deeply entrenched in India and that Bollywood is merely reflecting society’s ideals.

“They have been so internalized through our cinema itself,” he said, referring to an early example of the 1957 Indian epic “Mother India,” where actor Sunil Dutt’s skin was darkened to play the role of a farmer.

“We internalize it so much that it is part of a muscle memory, and we don’t even think about it.”

Bollywood’s endorsement of fairness products

But like discrimination on the basis of caste, discrimination on the basis of skin color is not confined to the big, Bollywood screen.

Seema Hari was born and raised in Mumbai. She said she was bullied at school for being dark-skinned and even taunted on the street by passersby who would tell her that she was bringing bad luck by showing her face in public.

“I did not know a reality where I was not depressed or suicidal in my childhood,” said Hari who is now a Snapchat software engineer and model based in Los Angeles.

She also campaigns against colorism, which she said is evident not only in Bollywood but on the shelves of Indian pharmacies and supermarkets that stock skin-lightening products.

Advocates say some of the best-known Bollywood stars are perpetuating the preference for lighter skin by lending their names and faces to the industry’s advertising campaigns promoting “fairness” creams.

“Some of the ads… were so blatantly racist… If you put a Bollywood star in it, it becomes normal; it becomes what people accept,” said Hari.

Society’s preference for lighter skin has led to a booming global business in skin lightening products. The international market for skin whitening cosmetics is predicted to reach more than $6.5 billion by 2025, according to a report by Global Industry Analysts.

While a handful of Indian celebrities have refused to be associated with skin lightening products, some big names have allowed their faces to be used to promote them in India.

Often dubbed the “King of Bollywood,” actor Shah Rukh Khan endorsed “Fair and Handsome,” a fairness cream for men, for years.

In 2013, a petition calling for an end to the product’s discriminatory advertising garnered more than 27,000 signatories. In 2016, Khan reportedly told The Guardian that he would never use the product himself, although it is unclear whether his sponsorship remains active. His agent did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.

Khan isn’t the only celebrity who has modeled for skin lightening products. For example, actor John Abraham currently endorses the Garnier Men PowerLight fairness moisturizer. “John endorses (the) entire Garnier men’s skin care and hair range and the communication is skin and hair care,” his manager, Minnakshi Das said.

In 2014, the Advertising Standard Council of India (ASCI) issued guidelines on the promotion of fairness products, stating that they cannot show dark-skinned people as depressed or disadvantaged.

While the independent body said they saw a “substantial shift” in discriminatory advertising, Bollywood stars continued to appear in promotions.

In February, the Indian ministry of health and family welfare proposed a draft bill that would ban advertisements that promote fairness creams, among other items. Law breakers could face a five-year jail term or a Rs 50 lakh fine (about $70,000).

“Celebrity endorsements are a huge part of the advertising industry,” said Shweta Purandare, secretary general of the ASCI.

“It commands about 24% of India’s total advertising expenditure… With new regulations… we expect to see celebrities being more cautious.” However, it is not clear from the bill whether celebrities themselves would be punished.

‘They just want to be white’

But skin lightening is not limited to over-the-counter creams.

“We have a few patients who aspire to be in Bollywood (and) who are too much into skin lightening treatments,” said dermatologist Dr. Sujata Chandrappa, who runs a beauty clinic in the southern city of Bangalore.

Clients ask her how certain dark-skinned stars became so fair-skinned. “This is deep rooted in the Indian psyche, that fairness is the prerequisite factor to enter into the Bollywood industry.”

She told CNN that she tries to talk some people out of the treatments, only offering the skin lightening procedure if a client has skin issues such as melasma, hyperpigmentation, sun damage or age spots. If a client insists on help to make themselves fairer in the absence of any other skin problems, she refuses to carry out the treatment.

“I get this feeling that I’m encouraging racism, which is not acceptable. But they just want to be white.”

However, conversations on colorism are starting to change.

Ten years ago, Indian NGO “Women of Worth” founded the “Dark is Beautiful” campaign that runs workshops in schools, colleges, workplaces and communities across the country to dismantle prejudiced attitudes towards dark skin.

They also initiated the petition against Shah Rukh Khan’s endorsement of the “Fair and Handsome” cream.

Nandita Das, actress and spokeswoman of the “Dark is Beautiful” movement, said the campaign has encouraged victims of colorism to share their stories, exposing the extent of India’s obsession with fairness.

“Suddenly, it was out in the open, something that had been there for so long in our matrimonial ads, cosmetics and products that we see all around,” Das told CNN. “We wonder why we haven’t talked about it much earlier.”

Das, who also screen-writes and directs, believes “we have a long way to go” before this billion-dollar industry casts a dark-skinned performer in a leading role.

She said her skin tone would make her “perfect” for a lower caste or class role. But when she plays “an educated or upper middle-class character, often the director, cinematographer, or makeup person tell you: ‘don’t worry, we’ll lighten your skin.’”

Das believes Bollywood directors have the freedom to cast whom they please, but she advises thinking “deeper into that prejudice.”

Some experts argue that Bollywood’s influence on society is bigger than ever, partly because of social media.

On-screen stars “used to be legends whom nobody saw” in real life, said film critic Subhash Jha. “(But) they’ve started to become very close to their fans, so the impact is larger.” The biggest Bollywood stars have tens of millions of followers on Instagram and TikTok, the video-sharing social networking service.

Hari believes that Bollywood celebrities could be doing much more to change attitudes across the country to dark skin. Imagine “Shah Rukh Khan walking away from a (fairness product) advertisement,” she said. “That itself will change so many minds.”

But does the industry’s persistent perpetuation of colorism suggest that it is racist?

“Deeply, fundamentally, irrevocably,” said Srivastava. “There are no standards of beauty linked to dark skin… There is no vocabulary within Bollywood to discuss race at all because in broader society, no such vocabulary or context has been allowed to develop.”

When it comes to using brownface in movies, “they don’t even think there’s a problem,” said film director Ghaywan. “That’s the biggest problem.”

Top image caption: Left, Actress Bhumi Pednekar at an event in Mumbai on January 16, 2020. Right, the actress in the movie “Bala.” Her skin was darkened to portray her character in the 2019 film.

This story has been updated to correct the year “Tropic Thunder” was released.