The air conditioner is nearly 100 years old, and yet it hasn’t evolved much – the technology is essentially the same as it was the day it was invented.

It has, however, changed our lives, making it possible for humans to thrive in places where heat would otherwise make life unbearable. Air conditioning is also essential to businesses and technologies that rely on controlled temperatures and humidity, such as the very internet servers that are sending this story to your device.

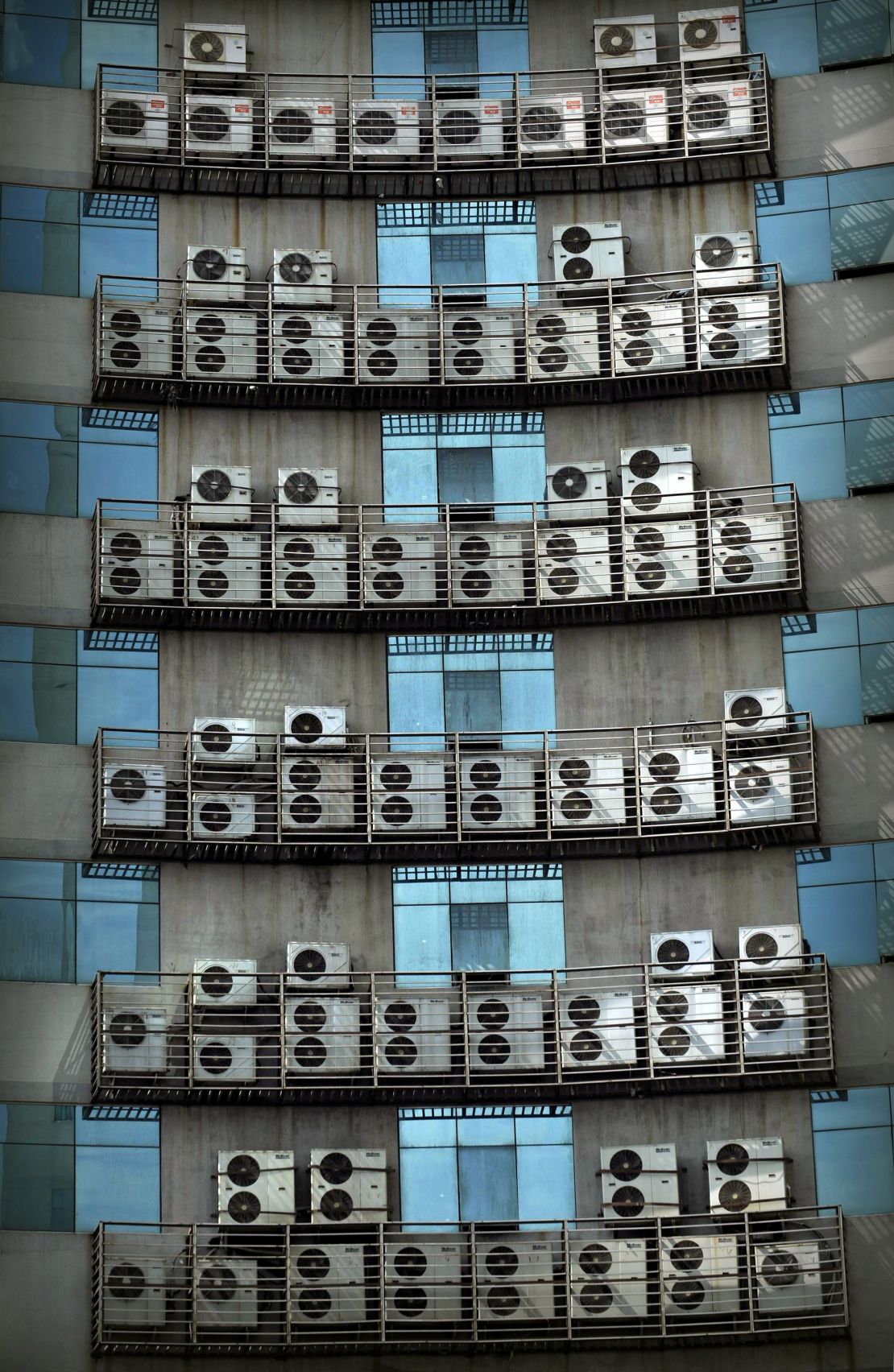

But this all comes at a cost: The cooling of our air is responsible for 10% of the planet’s electricity consumption, according to the International Energy Agency. And as the world heats, demand for air conditioners will only grow, especially in developing countries. This, in turn, will increase the impact that cooling appliances have on the climate, thus warming the Earth further and creating a vicious cycle.

The current technology is unsustainable. That’s why a new coalition – led by India’s government and America’s Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), a nonprofit environmental research organization – has launched the Global Cooling Prize, a $1-million competition to design the next generation of air cooling systems.

“The first home air conditioner was brought to market in 1926 by Willis Carrier, who’s long since dead,” said RMI’s managing director, Iain Campbell, in a phone interview. “If we brought him back to life and showed him today’s air conditioning product, not only would he know what it is, he could tell you how it works.”

The prize

There are 1.2 billion room air conditioning units installed today, but that figure will soar to 4.5 billion by 2050, according to an RMI report. “The impact of that on electricity demand is going to be huge,” said Campbell, who co-authored the report. “The dilemma is that it comes at an environmental cost we can’t afford. It’s a kind of climate threat you don’t see much in the rear view mirror, but when you look at what’s in front of you, it’s massive,”

The Global Cooling Prize sets specific guidelines for participants, who were tasked with designing a cooling solution with five times less climate impact than those popular today, meaning they could help counteract the environmental effects of the expected growth in demand.

To allow for this improved efficiency, proposed designs were allowed to be more expensive than current air conditioners (though no more than twice as much). The higher price would then, in theory, be offset by cheaper running costs. “If a technology is twice as expensive and uses a quarter of the electricity, the simple payback is about two and a half years,” explained Campbell.

Entrants had to abide by seven additional rules, most of which were designed to prevent what Campbell called “unintended consequences,” such as excessive use of water or rare earth minerals, as well as limitations on fuel combustion and insulation.

The prize’s judges have shortlisted eight finalists, who will now build functioning prototypes that will be tested both in a lab and in real-world conditions at an apartment block in Delhi. “We’re going to do a 60-day test at the peak of the Delhi summer,” said Campbell. “India will be the largest market for cooling over the next 30 years, going from under 14 million air conditioning units today to (nearly) a billion by 2050. They would need to double the size of their power system to achieve that.”

The finalists

The competition attracted over 2,100 participants from 95 countries. From a long-list of 139 teams, eight finalists were awarded $200,000 to develop prototypes and ship them to India for testing in the summer of 2020.

Three of the eight finalists are from India, three are from the US and one each from the UK and China. “We have three major manufacturers, one university with a very advanced technology and then four smaller entities, coming at this from outside the industry with some very novel and different approaches,” said Campbell.

The proposed designs employ a wide range of technologies, from vapor compression to evaporative cooling. Barocal, a Cambridge University spin-out startup, uses solid-state cooling technologies instead of traditional liquid refrigerants that may leak out over time. Meanwhile a proposal from Kraton, a Texan chemical engineering company, simply uses water, completely doing away with the main mechanical component of air conditioners, the compressor, to make the design more scalable and affordable.

Other entrants focused on the limitations of current air conditioning units, such as the lack of control over both temperature and humidity at the same time. The design proposed by US startup M2 Thermal Solutions allows users to set both a specific temperature and the level of humidity in a room.

It’s difficult to tell what these proposed new machines will look like before the actual prototypes are built, but it’s arguable that they will also debut a new aesthetic, as most of the shortlisted designs are based on fundamentally different technology compared to traditional devices.

The challenge

The overall winner, announced in November 2020, will be awarded $1 million in prize money. This is when the real challenge begins: convincing the world that traditional air conditioners need replacing. “The current A/C industry is worth more than $100 billion and has a well-established value chain – from manufacturing to distribution to after-sales support,” said Kraton’s senior vice president, Vijay Mhetar, in an email. “Any new design will need to have minimal barriers for customer adoption and have a similar supply chain established.”

According to Xavier Moya from Barocal and the University of Cambridge, the main challenge is to convince people to buy an air conditioner based on its performance and climate impact, rather than just its price. “This change in consumer perception could be also aided by phasing out the sale of environmentally unsustainable designs,” he added in an email.

But why has the air conditioner changed so little since it was invented back in 1902? According to Ryan Melsert, CEO of finalists M2 Thermal Solutions, it may be due to an “out-of-sight out-of-mind” attitude. “These systems are all around us, in the closets and basements of our homes, in the utility rooms of our businesses, under the hoods of our vehicles,” he said in an email. “But because they are rarely seen, customers are tolerant of this lack of innovation.”

Over the last century, the vast majority of industry investments have gone into making traditional designs cheaper, said Vijay Mhetar, although the best model in the market today only has a theoretical efficiency – the ratio between heat removed and power used – of 14%. That’s low compared to more efficient technologies like lighting and solar panels, which today achieve 67% and 28% respectively in their fields, according to the RMI report.

“We believe a step change in performance will likely come from a radically new design, invented outside the industry,” he said.