Editor’s Note: Artist Takashi Murakami is CNN Style’s latest guest editor. He has commissioned a series of features on identity.

Francis Bacon’s work has always been instantly recognizable. “Nightmarish horror” was how art critic David Sylvester described it in 1954, citing the general critical response to his paintings. Raw, dark and visceral, Bacon’s images were disquieting from the outset.

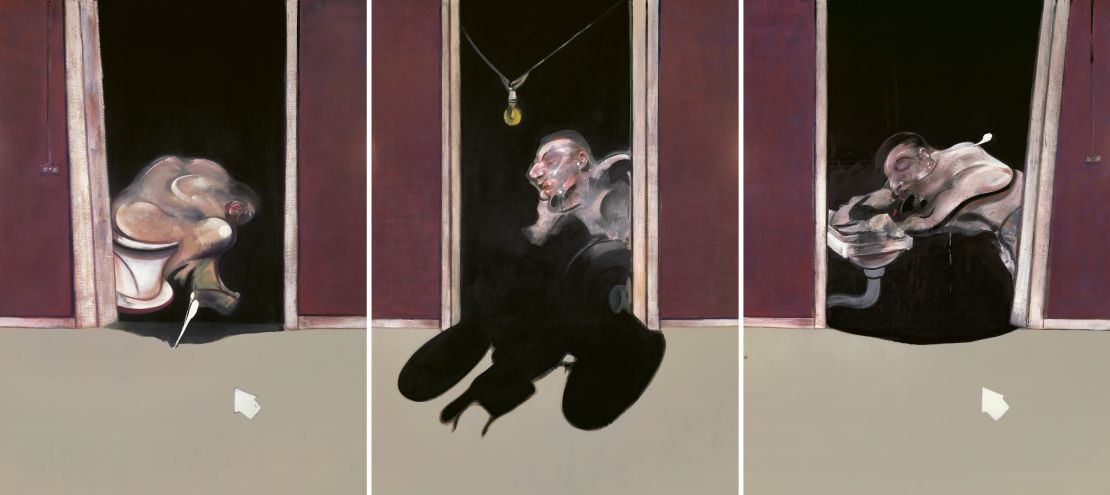

Just look at 1944’s “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion,” his first masterpiece. Here was an early example of what became his favored form: a triptych of disturbing imagery featuring distorted limbs, eyeless heads and open snarling mouths – the teeth bared and ready to savage – all painted on a glowing orange backdrop.

Bacon was already in his mid-30s by then – “a late starter,” as he put it. Yet this single painting dramatically announced his arrival as a major artist. At the time, London was being bombarded with V-1 and V-2 rockets from Nazi Germany but Bacon drew his inspiration from elsewhere. The image transcended traditional religious iconography.

Stylistically, Bacon was freed up to experiment, his artistic identity shaped by the radical work of his early hero, Picasso (whose 1927 show in Paris left a profound impression on the Irish-born painter).

Just as importantly, he was inspired by Greek tragedy; he was obsessed with the playwright Aeschylus and the Furies of his “Oresteia” trilogy. Tellingly, when he talked about the Furies, goddesses of vengeance in classical mythology, Bacon would habitually quote a passage from the plays: “The reek of human blood smiles out at me.”

In his famous 1944 work, Bacon – consciously it seems – painted the Furies and gave us an indelible image of menace, anguish, terror and revenge. The triptych somehow sears into the brain. Seen in the flesh, it’s an image that is hard to get out of your head. The painting was first exhibited in April 1945, in the final months of World War II. The allies were just liberating the Nazi concentration camps, and haunting images were emerging – grotesque piles of bodies and pitifully emaciated prisoners. Bacon’s masterpiece jangled a nerve. It still does.

Early influences

Bacon painted largely from memory and photos, in a small, chaotic studio in London’s South Kensington (the studio has since been reconstructed, complete with its original contents, at the City Gallery in Dublin). We know the artists he especially admired: Michelangelo, Velázquez, Degas, Van Gogh and Ingres. But critics have also identified some of his direct sources. A life mask of the poet William Blake, for instance, served as the basis for a series of small portraits in 1955.

Eadweard Muybridge’s pioneering 19th century photos of human and animal movement, notably of men wrestling, had a more enduring impact. The resulting paintings are sometimes intensely sexual – or, to be more precise, homoerotic. Bacon knew that he was gay from an early age. His authoritarian father threw him out of the family home in Dublin for wearing his mother’s clothes, and he took himself to London aged 17.

Today in the British capital, the Gagosian gallery is exhibiting what it describes as “two of the most uninhibited images that Bacon ever painted.” They were executed long before homosexual acts between men was decriminalized in England in 1967. “Two Figures” (1953) depicts two naked men, blurred and grappling like wrestlers on crumpled sheets. Is one pinning the other down? Is this agony, ecstasy or a bit of both? Their faces are distorted – we can’t tell for sure.

“Two Figures in the Grass” (1954) is a passionate coupling with lots of pinky-white flesh. Buttocks, a leg, an ear and hair, all half-hidden in the blades of grass. The patch of grass is fenced in. Bacon often liked to frame the space – thin vertical and horizontal lines within his paintings – to somehow intensify the image, to box it in.

Another key inspiration came from one of silent cinema’s best-known sequences: a still image of a screaming woman, her glasses smashed and her face bloodied, stood on Odessa’s famous steps in Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 film “Battleship Potemkin.”

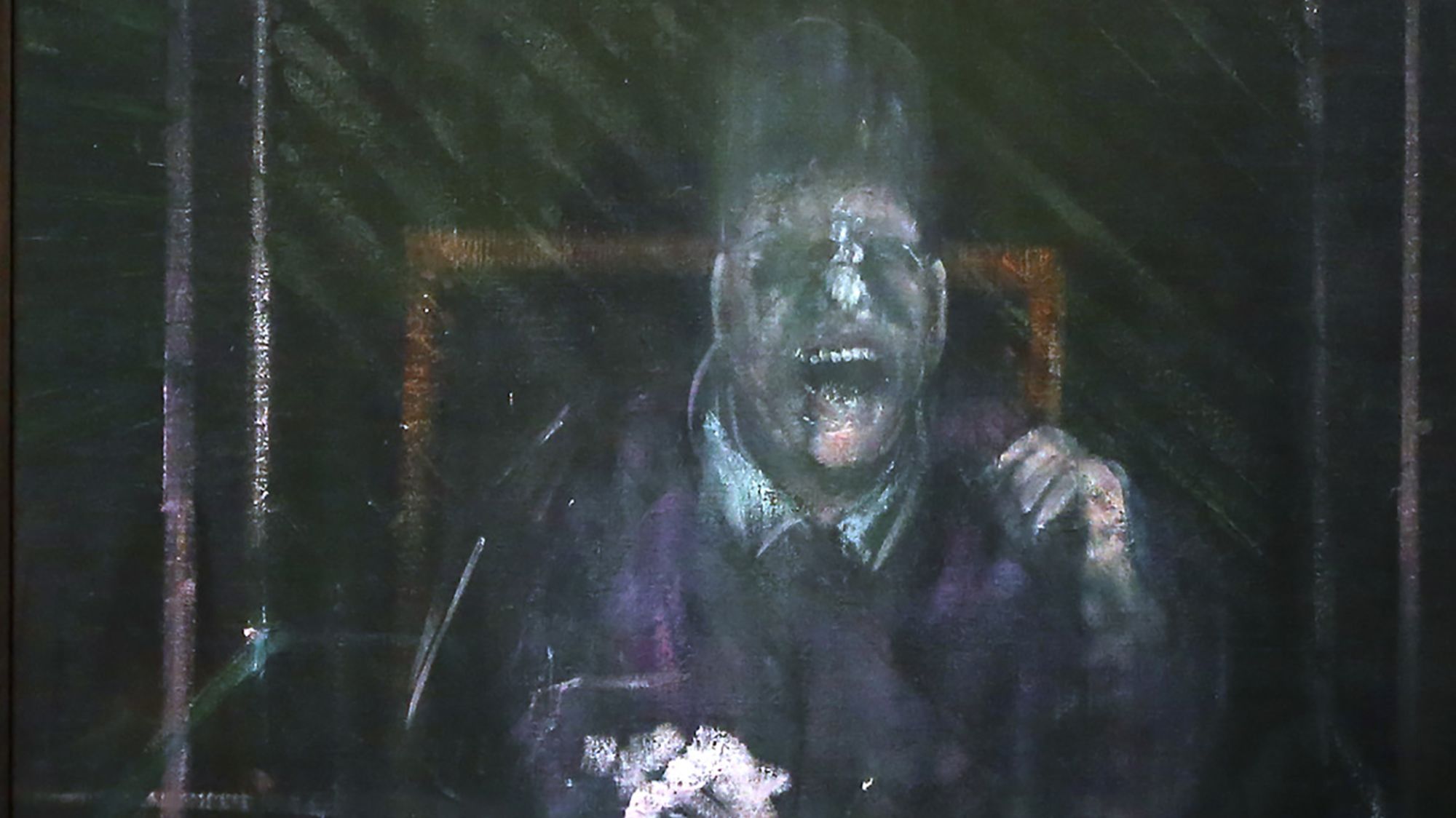

Bacon’s series of screaming popes, meanwhile, were inspired by Velázquez’s “Portrait of Pope Innocent X.” The paintings helped establish his reputation in the early 1950s. In Velázquez’s original (circa 1650), the papal mouth was clamped firmly shut. But in most of Bacon’s versions, of which there were around 50, he is screaming and caged. In interviews, Bacon said that he was “always very obsessed by the actual appearance of the mouth and teeth,” and that he had “always hoped to paint the mouth like Monet painted a sunset.”

‘Saying something that matters’

The fact is, Bacon fundamentally altered figurative painting in the 20th century. His aim wasn’t so much to create a likeness, but a sense of presence.

Sometimes, he just did this viscerally. Viewing his work, we feel like we’ve stumbled into a human abattoir. At other times, his figures appear like apparitions, wraiths. Most of his subjects were his friends and lovers, his small circle of intimates or his companions from the Colony Room Club, the private members’ club he frequented in London’s Soho (where he was known to consume a lot of champagne).

Although Bacon was never filmed painting, we know more about his practice than perhaps any other important 20th-century artist. And this is for one simple reason: his friendship with the aforementioned critic and curator, David Sylvester.

Sylvester wrote about Bacon with rare acuity and accessibility over a period of some 40 years. His interviews with Bacon, first published in 1975 and later expanded, remain a primary source for understanding the artist’s work. Sylvester’s conclusion was, he wrote, that “everyone feels (whether they like the work or not)” that Bacon “is saying something that matters about the times in which we live.”

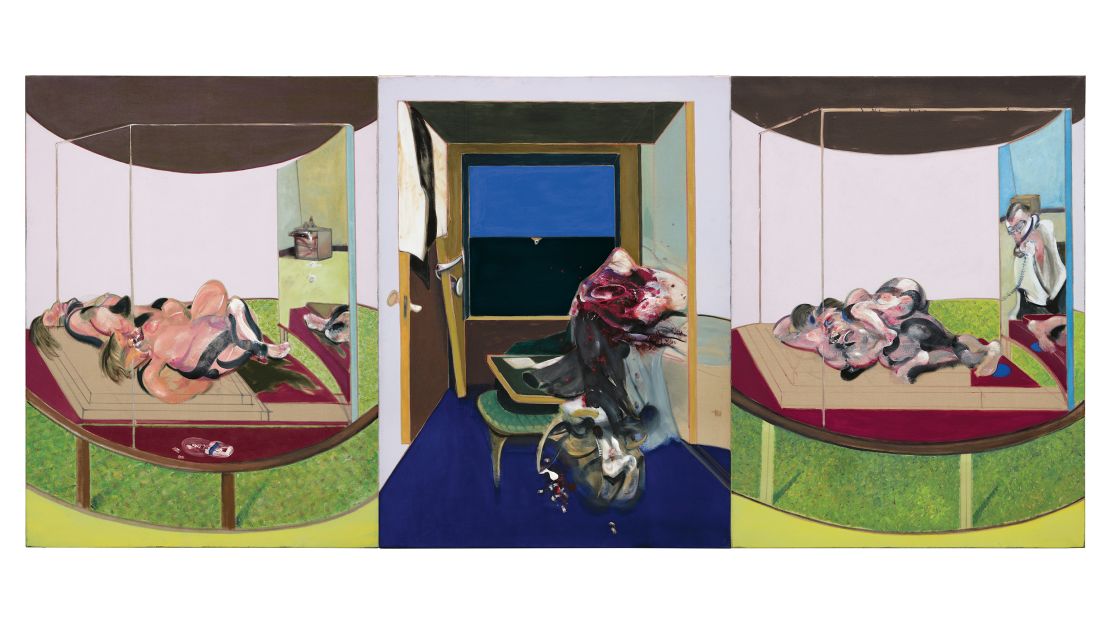

Sylvester felt that Bacon achieved his greatest work in 1974. A sudden and shocking bereavement reinforced his artistic identity. George Dyer, a handsome small-time crook who’d become Bacon’s lover, was the subject of many portraits after the pair met in 1963. Dyer’s suicide in a Paris Hotel in 1971, just days before a Bacon retrospective at the Grand Palais, triggered a series of searing triptychs. In them, Bacon aimed to convey what he described as “all the pulsations of a person.” In Sylvester’s view, they are perhaps “the most moving things he ever did.”

Here was a conscious act of exorcism by Bacon – paintings created in memory of Dyer. One of them, “Triptych May-June 1973,” is absolutely unsparing, a painting of pity and terror.

Each of the three images is framed by a door. In the left panel, Dyer is doubled up on a toilet, just as his body was found. On the right panel, he is depicted throwing up into a sink. In the center panel, Dyer’s figure crouches in the darkness beneath a hanging, naked light bulb. He casts a shadow – a bird of prey perhaps, or a Fury. Sylvester thought that this was probably Bacon’s greatest painting.

An artist’s legacy

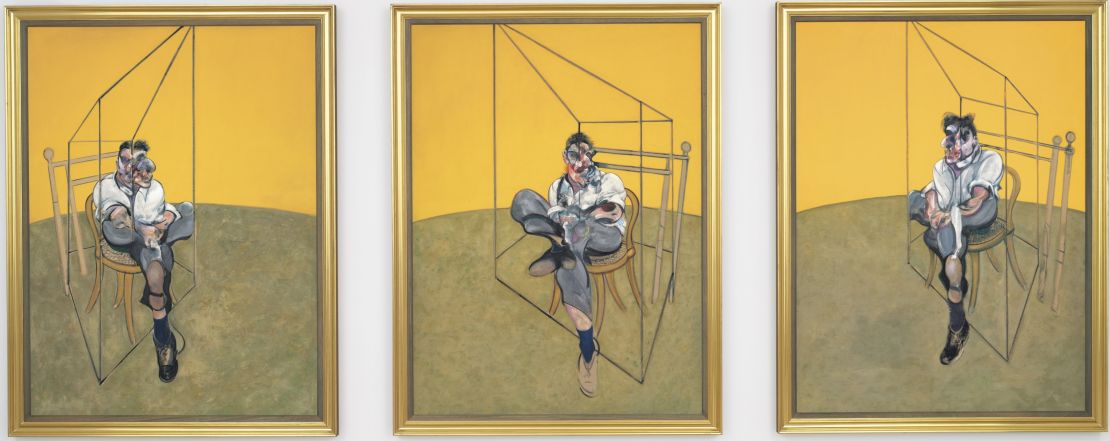

Bacon’s market value has risen by leaps and bounds since his death in 1992. Damien Hirst collects, telling the Guardian in 2006 that he owned five of his paintings. In 2013, “Three Studies of Lucian Freud” (1969) sold at Christie’s in New York for $142.4 million, then a world auction record for a work of art. From September 2019, the Pompidou Centre in Paris is putting on a new show of Bacon’s work.

Bacon told Sylvester that “no artist knows in his own lifetime whether what he does will be the slightest good, because I think it takes at least seventy-five to a hundred years to sort itself out.” But he was nonetheless aware that he had made an impact. Three retrospectives were held during his lifetime: in 1962 and 1985 at Tate Britain, and the 1971 show at the Grand Palais.

I was filming the 1985 Tate exhibition when Bacon and his then companion (and later heir) John Edwards suddenly wandered into the space. Bacon quickly spotted the camera and they swiftly turned around. We missed the shot. Francis Bacon was essentially a private man who wasn’t remotely interested in celebrity. But he definitely wanted his work to be seen.

Top image: “Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X” by Francis Bacon. “Francis Bacon: Couplings” is on at the Gasogian in London until August 3, 2019. “Bacon: Books and Painting” opens at the Pompidou Centre on September 11, 2019.