In the 1930s, hundreds of thousands of poverty-stricken Dust Bowl refugees poured into California from the parched Midwest in search of food, jobs and dignity. Meanwhile, much of the country, mired in its own Depression-fueled misery, was oblivious to the ecological and social catastrophe at hand. Armed with a camera and a good dose of outrage and compassion, Dorothea Lange set out to change that.

It’s a recurring theme throughout modern history, the downtrodden and their advocates. For Lange, photographing the subjugated was her way of aiding them. She pioneered a use of the camera as a powerful catalyst for social change, and in an era erupting with humanitarian conflict, her legacy resonates.

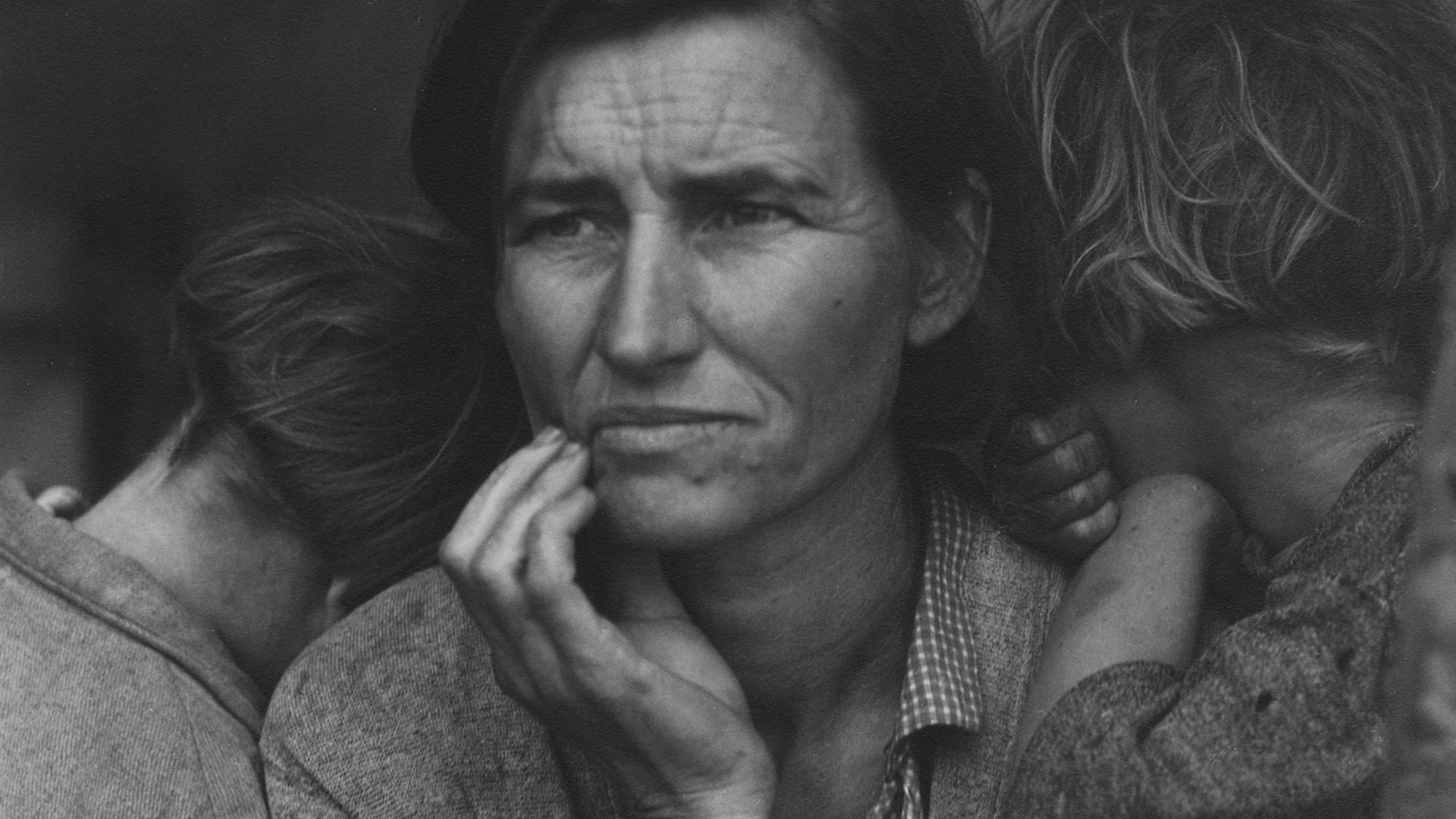

Lange’s Depression-era photos are so tightly woven into the fabric of American culture that, for many of us, our memories of that period are inseparable from the scenes she captured with her camera, from her iconic portrait of maternal demoralization and perseverance, “Migrant Mother” (1936), to her over-farmed fields, ramshackle lean-to tents and dusty jalopies.

Her mission was not just personal: Lange had been hired by the photographic unit of the Farm Security Administration – a progressive New Deal agency founded to alleviate poverty – to document the growing migrant crisis. But her images went far beyond bureaucratic reportage. A skilled portraitist, Lange famously possessed an ability to return a sense of dignity to a group that had been routinely dehumanized. She had also come of age during the modernist transformation of photography into an art form, and turned her lens on America’s social ills with an aesthetically gripping style that captured the country’s imagination.

“She and the FSA were clearly dedicated to improving the lives of migrants and drought refugees by creating public sympathy through the use of powerful imagery. And of all the FSA photographers, I think Lange was the most successful at making images that were factual, but which also packed an emotional wallop,” Drew Johnson, the curator of photography and visual culture at the Oakland Museum of California, said in an email. Johnson curated “Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing,” a major traveling exhibition now on view at the Barbican in London (organized by Alona Pardo and Jilke Golbach).

Lange might not have been able to effect policy changes at the government level, but her images for the FSA, picked up by newspapers across the country, conveyed the crisis to a wide audience in relatable terms. (The author John Steinbeck used them for inspiration in his epic 1939 Dust Bowl tale “The Grapes of Wrath.”)

“The political impact of her work was felt in much the same way as that of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ before the Civil War in creating a heightened public awareness of injustice,” said Johnson. “As Lange’s boss at the FSA, Roy Stryker, said, ‘We introduced Americans to America.’”

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1895, Lange contracted polio as a young girl and walked with a noticeable limp – an ordeal that some credit with fostering her fierce determination. She learned professional photography skills while working in New York in her early 20s, and then landed in San Francisco. There, she fell in with the era’s bohemian artists and writers, including the painter Maynard Dixon, who she eventually married. This crew frequented her studio, where she ran a successful portrait business catering to the city’s wealthy elite.

When the Depression hit, a humanistic call to arms led Lange to the streets, where she famously captured crowded breadlines. Her second marriage, to the agricultural economist Paul Taylor, helped get her out into the fields with the destitute pickers, who she’d treat like portrait subjects.

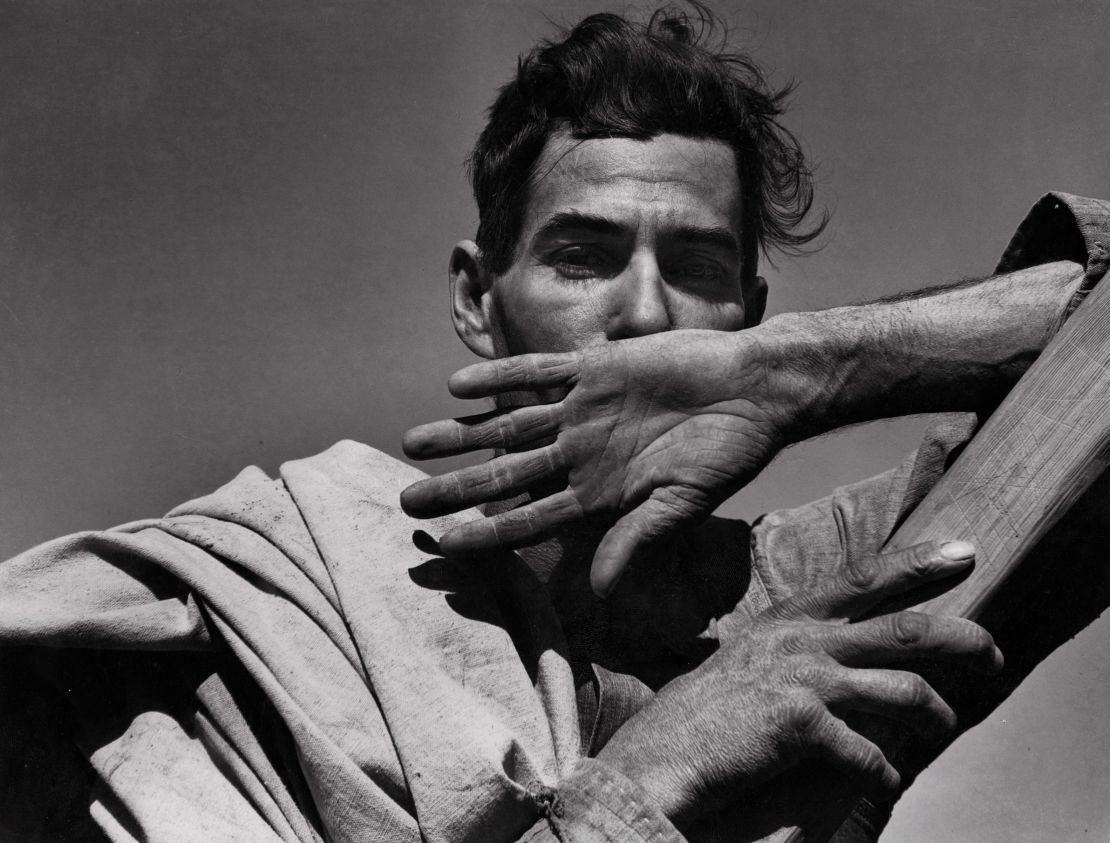

“She encouraged empathy and identification with her subjects using techniques such as shooting from a low angle to emphasize a person’s strength and dignity, and moving in close to crop out superfluous details,” Johnson said. “Most of all, she spent time with people, establishing rapport and getting their story, often before even taking out her camera.”

If Lange’s photos introduced Americans to America, to many, they also introduced the country’s systemic racism, from her images of black sharecroppers and segregation in the South, to subjugated Filipino and Mexican farm laborers in California, to her early 1940s series documenting the forced relocation and internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

“There are the striking echoes in her work of issues we’re reading about in today’s headlines. Refugee crises, immigration, racism, separation and imprisonment of families, migrant farm workers,” Johnson said.

Those uncanny parallels aside, in our highly divisive political climate, where words seem to have lost their meaning and the truth is in constant question, the kinds of images that Lange pioneered feel especially urgent in the effort to expose widespread social injustice.

“I honestly cannot think of a photographer who has had a more powerful legacy of inspiring younger generations of socially motivated photographers,” says Johnson. “Her combination of integrity, empathy, and concern for truth – all presented with a beauty that does not overwhelm the larger story – never seems to become dated.”

And in an era when images have a nearly instantaneous and incomparably vast reach, whether coming from professional photojournalists or more amateur talents, the visual has never had so much power to influence public perception. And Lange’s legacy can be seen everywhere. Take, for instance, John Moore’s photos of border patrol agents and immigrant families, Lynsey Addario’s portraits of Syrian and Iraqi refugees, or viral images documenting the escalating tensions between law enforcement and black communities by such photographers as Devin Allen in Baltimore, and Patience Zalanga in Ferguson, Missouri.

For Magnum photographer Matt Black, whose ongoing series “The Geography of Poverty” captures America’s urban and rural poor in a way that inevitably summons Lange, his photography comes out of “a desire to make certain realities more visible, both for myself and because I think they need to be seen.”

“Many things are different. Photography is more accessible, more voluminous, and the visual language is maybe a bit more fluent,” he said in an email, referring to the world in which Lange’s photos first circulated.

“But the main question remains the same: Where do you stand, and which direction do you point your voice, up or down?”

“Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing” is on at the Barbican in London until Sept. 2, 2018.

Top image: Close-up of “Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California” (1936) by Dorothea Lange