As biotechnology advances, so too may our ideas of what it means to be human.

Today, we can alter our bodies in previously unimaginable ways, whether that’s implanting microchips, fitting advanced prosthetic limbs or even designing entirely new senses.

So-called transhumanists – people who seek to improve their biology by enhancing their bodies with technology – believe that our natural condition inhibits our experience of the world, and that we can transcend our current capabilities through science.

Ideas that are “technoprogressive” to some are controversial to others. But to photographer David Vintiner, they are something else altogether: beautiful.

“Beauty is in the engineered products,” said Vintiner, who has spent years photographing real-life cyborgs and body-modifiers for his upcoming book, “I Want to Believe – An Exploration of Transhumanism.”

Made in collaboration with art director and critic Gem Fletcher, the book features a variety of people who identify, to some degree, as “transhuman” – including a man with bionic ears that sense changes in atmospheric pressure, a woman who can “feel” earthquakes taking place around the world and technicians who have developed lab-made organs.

Fletcher was first introduced to the transhumanist subculture via the London Futurist Group, an organization that explores how technology can counter future crises. Upon meeting some of its members, the London-based art director approached Vintiner with the idea of photographing them in a series of portraits.

“Our first shoot was with Andrew Vladimirov, a DIY ‘brain hacker,’” Vintiner recalled in a phone interview. “Each time we photographed someone new, we asked for referrals and introductions to other key people within the movement.”

Though the photographer admitted that the transhumanists’ claims can seem outlandish at first, he soon saw the appeal of technological self-enhancement. “If given the chance, how would you design your own body and what would you want it to say about you?” he asked.

Redefining human experience

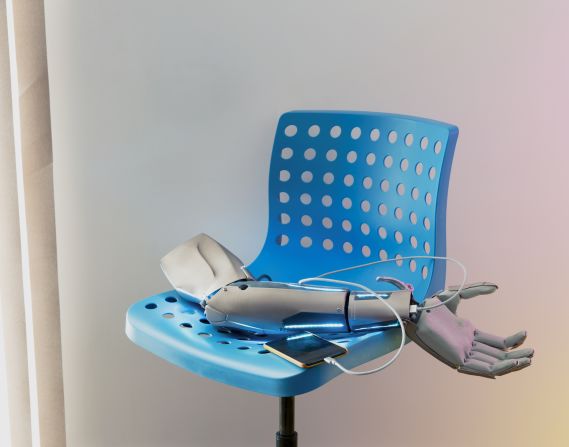

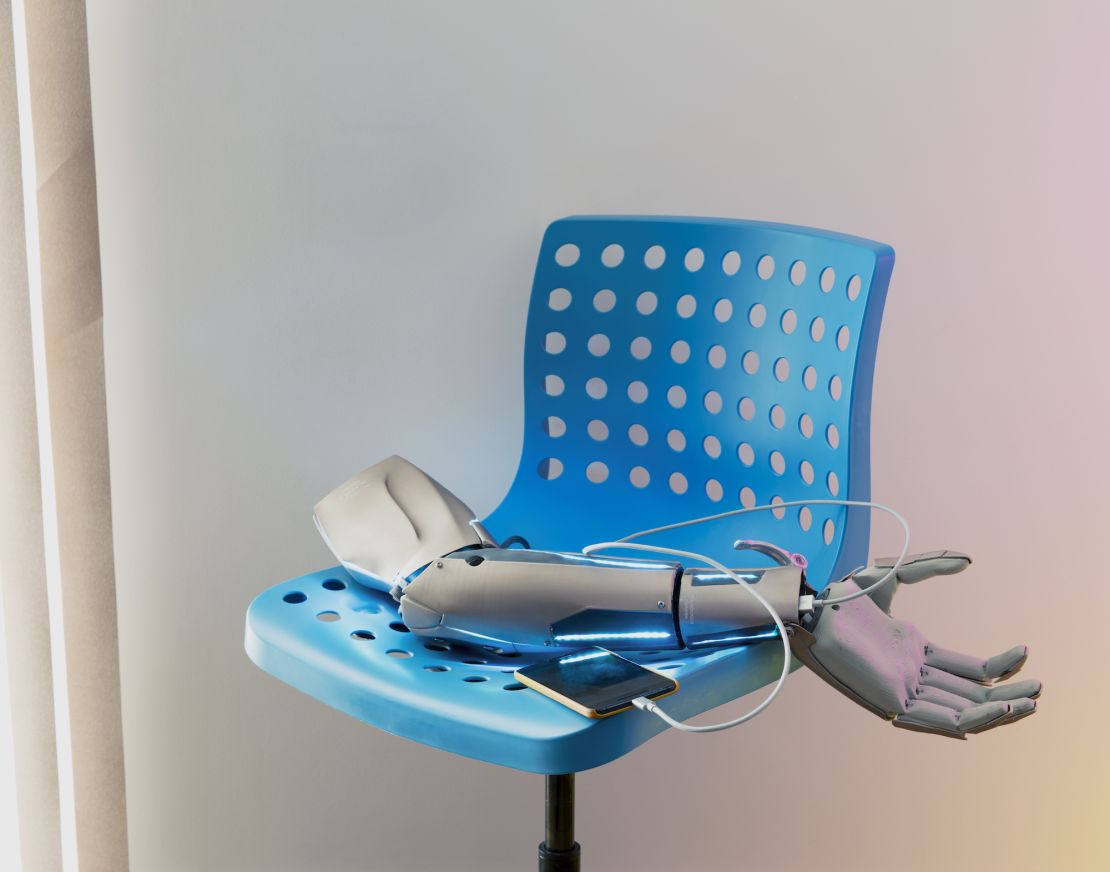

One of Vintiner’s subjects, James Young, turned to bionics after losing his arm and leg in an accident in 2012. Young had always been interested in biotechnology and was particularly drawn to the aesthetics of science fiction. Visualizing how his body could be “re-built,” or even perform enhanced tasks with the help of the latest technology, became part of his recovery process.

But according to the 29-year-old, the options presented to him by doctors were far from exciting – standard-issue steel bionic limbs with flesh-colored silicone sleeves.

“To see what was available was the most upsetting part,” Young said in a video interview.

“What the human body can constitute, in terms of tools and technology, is such a blurry thing – if you think about the arm, it’s just a sensory piece of equipment.

“If there was anyone who would get their arm and leg chopped off, it would be me because I’m excited about technology and what it can get done.”

Japanese gaming giant Konami worked with prosthetics sculptor Sophie de Oliveira Barata to design a set of bionic limbs for Young. The result was an arm and leg made from gray carbon fiber – an aesthetic partly inspired by Konami’s “Metal Gear Solid,” one of the then-22-year-old’s favorite video games.

Beyond the expected functions, Young’s robotic arm features a USB port, a screen displaying his Twitter feed and a retractable dock containing a remote-controlled drone. The limbs are controlled by sensors that convert nerve impulses from Young’s spine into physical movements.

“Advanced prosthetics enabled James to change people’s perception of (his) disability,” said Vintiner of Young, adding: “When you first show people the photographs, they are shocked and disconcerted by the ideas contained within. But if you dissect the ideas, they realize that they are very pragmatic.”

Young says it has taken several years for people to appreciate not just the functions of advanced bionic limbs but their aesthetics, too. “Bionic and electronic limbs were deemed scary, purely because of how they looked,” he said. “They coincided with the idea that ‘disability is not sexy.’”

He also felt there was stigma surrounding bionics, because patients were often given flesh-colored sleeves to conceal their artificial limbs.

“Visually, we think that this is the boundary of the human body,” Young said, referring to his remaining biological arm. “Opportunities for transhumanists open up because a bionic arm can’t feel pain, or it can be instantly replaced if you have the money. It has different abilities to withstand heat and to not be sunburned.”

As Vintiner continued shooting the portraits, he felt many of his preconceptions being challenged. The process also raised a profound question: If technology can change what it is to be human, can it also change what it means to be beautiful?

“Most of my (original) work centers around people – their behavior, character, quirks and stories,” he said. “But this project took the concept of beauty to another level.”

Eye of the beholder

Science’s impact over our understanding of aesthetics is, to Vintiner, one of the most fascinating aspects of transhumanism. What he discovered, however, was that many in the movement still look toward existing beauty standards as a model for “post-human” perfection.

Another subject of Fletcher and Vintiner’s book is Sophia, a robot designed by scientists David Hanson and Ben Goertzel at Hanson Robotics. Sophia is one of the most advanced humanoid robots to date.

Speaking to CNN Style in 2018, Hanson said that Sophia’s form would resonate with people around the world, and that her appearance was partly inspired by real women including Hanson’s wife and Audrey Hepburn, as well as statues of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti.

But with her light hazel eyes, perfectly arched eyebrows, long eyelashes, defined cheekbones and plump lips – Sophia’s appearance arguably epitomizes that of a conventionally beautiful Caucasian woman.

“When I photographed Ben Goertzel, he vocalized how he took no time to consider how he (himself) looked – it was of no interest to him,” the photographer recalled of the photo shoot.

Vintiner saw a certain irony: that someone who was unconcerned about his own appearance would nonetheless project our preoccupation with beauty through his company’s invention.

It also served as a reminder that attractiveness may be more complex than algorithms can ever fathom.

“I fear that if we can design humans without any of the ‘flaws’ that occur in our biological makeup, things will be pushed further and further towards a level of perfection we can only imagine right now.” Vintiner said. “Look at how plastic surgery has altered our perception of beauty in a very short space of time.

“If the transhumanists are right and we, as humans, can live to be several hundreds of years old, our notion of beauty and the very meaning of what it is to be human will change dramatically.”

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the launch of “I Want to Believe – An Exploration of Transhumanism,” as well as a Kickstarter campaign and accompanying photo exhibition, have been temporarily postponed.