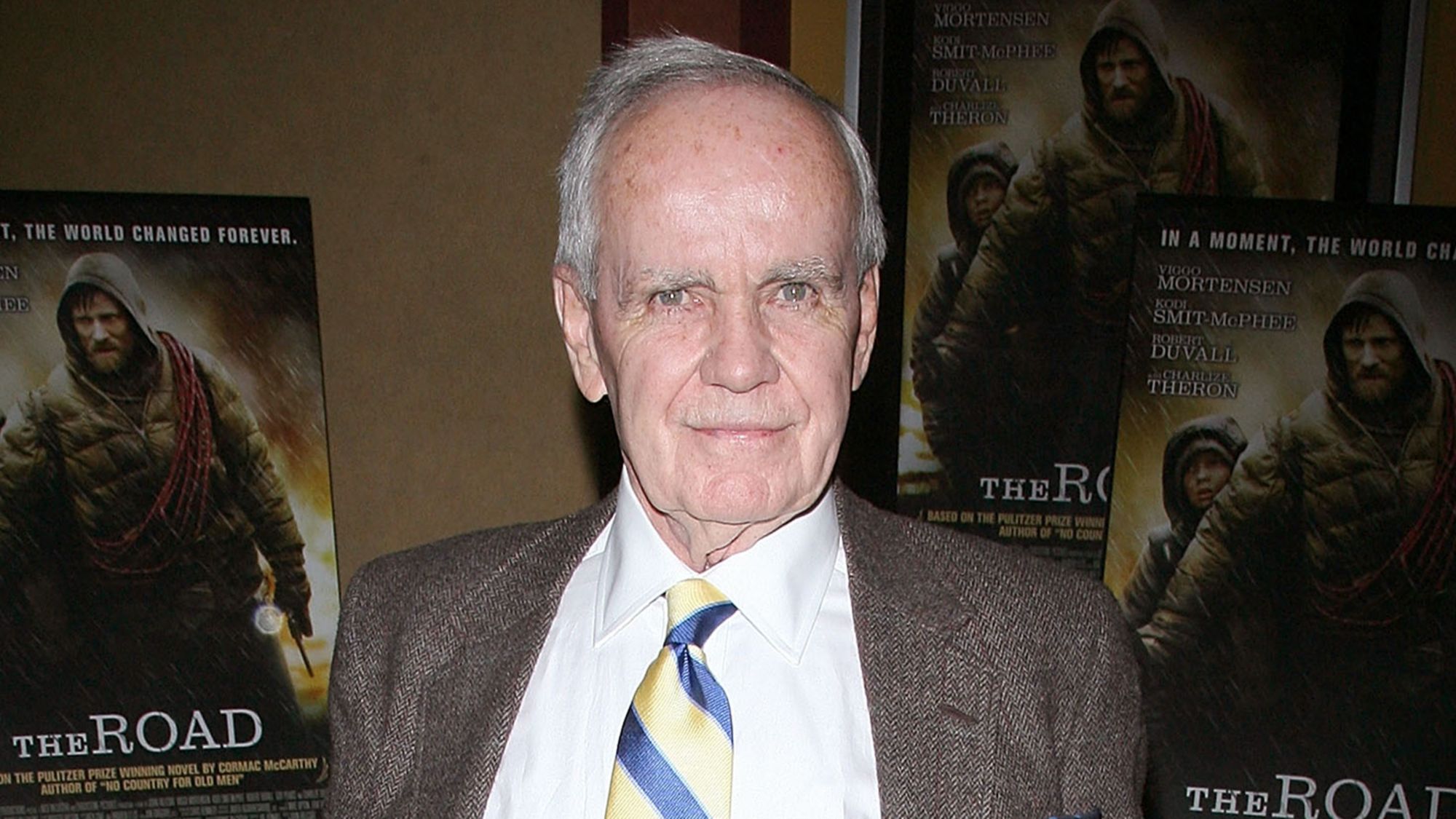

Cormac McCarthy, long considered one of America’s greatest writers for his violent and bleak depictions of the United States and its borderlands in novels like “Blood Meridian,” “The Road” and “All the Pretty Horses,” died on Tuesday, according to his Penguin Random House publisher Alfred A. Knopf. He was 89.

McCarthy died of natural causes at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Knopf said.

Over a nearly 60-year career, McCarthy – hailed by the late literary critic Howard Bloom as the “true heir” of Herman Melville and William Faulkner – wrote a dozen novels, many of them critically celebrated if not commercial hits, though he would eventually achieve both. For years, he wrote while living on grants, most notably the MacArthur “genius grant,” which he was awarded in 1981.

Despite accolades, McCarthy remained relatively obscure for much of his career; as recently as 1992, 27 years after his first book was published, the New York Times Book Review said he “may be the best unknown novelist in America.”

Both before and since, McCarthy was seen and portrayed in the media as reclusive, eschewing the kind of book tours, signings, interviews and lectures other renowned writers would see as professional obligations. But McCarthy famously abhorred talking about his books, which principally featured male characters and profuse violence, as well as sparse punctuation.

Still, he was a “writer’s writer,” the Times reported, with a cult following and a reputation “far out of proportion to his name recognition or sales.”

“I never had any doubts about my abilities,” McCarthy told the Times in one of his few interviews. “I knew I could write. I just had to figure out how to eat while doing this.”

That obscurity changed with “All the Pretty Horses,” the first installment of his “Border Trilogy,” which became a bestseller and won the 1992 National Book Award, at last marrying the critical acclaim he’d enjoyed with mainstream success.

His Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Road,” which followed a father and son traveling through a post-apocalyptic America, further catapulted McCarthy to popularity, thanks in part to Oprah Winfrey selecting the novel for her book club. McCarthy, in turn, granted Oprah his first and only television interview.

“The Road” was also one of several of McCarthy’s books adapted for film, most notably the Coen Brothers’ adaptation of “No Country for Old Men,” which won four Academy Awards, including best picture.

The author was born Charles McCarthy Jr. on July 20, 1933, in Providence, Rhode Island. His family moved when he was still young to Knoxville, Tennessee, where his father was an attorney for the Tennessee Valley Authority. His was a relatively comfortable childhood, one that played out on a plot of wooded land in a large white house with maids.

“We were considered rich,” he told the Times, “because all the people around us were living in one- or two-room shacks.”

For all his later literary achievements, McCarthy was not a voracious reader in his childhood or adolescence. It wasn’t until he served in the US Air Force after dropping out of the University of Tennessee that McCarthy began reading extensively, in his barracks while stationed in Alaska, he told the Times.

He would later move to Chicago, where he finished his first novel and in 1961 married his first wife, Lee Holleman, with whom he had a son. They soon divorced.

That novel, “The Orchard Keeper,” was published in 1965, after shepherding by the famous Random House editor Albert Erskine, who also edited Faulkner. Erskine, who died in 1993, would go on to edit McCarthy for two decades despite the fact, Erskine admitted to the Times, that McCarthy’s books never sold.

“Outer Dark” followed in 1968 and “Child of God” in 1973, after a stint in Ibiza and McCarthy’s subsequent return to Tennessee with his second wife, Annie DeLisle. But still, they lived in “total poverty,” DeLisle once said, “bathing in the lake.”

“Someone would call up and offer him $2,000 to come speak at a university about his books,” DeLisle told the New York Times. “And he would tell them that everything he had to say was there on the page. So we would eat beans for another week.”

But McCarthy didn’t become a writer to make money, instead “maybe simply, because I can do it,” he told the Maryville-Alcoa Times, a Tennessee newspaper, in 1971. “There are a lot of easier ways to make money. I could sell tickets to people and let them watch while I was run over by a truck.”

His next novel, “Suttree,” was published in 1979. McCarthy was awarded the MacArthur Fellowship two years later, giving him financial security to focus on writing. McCarthy left DeLisle and used the money to abscond to the Southwest, where he spent the next several years steeped in research for “Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West,” published in 1985.

The historically based novel – widely regarded as McCarthy’s masterpiece – follows a brutal gang of scalp hunters as they journey across the Southwest, massacring Apache and members of the Mexican Army.

“All the Pretty Horses” was published in 1992 and was followed over years by “The Crossing” and “Cities of the Plain,” which together comprise “The Border Trilogy” – in all a more idyllic ode to the region that recounted the adventures of two young cowboys.

“No Country for Old Men” in 2005 received a less positive critical reception than McCarthy’s earlier novels, though its standing improved with time. The book, which the author began as a screenplay, did well as a movie under the direction of Joel and Ethan Coen, with the talents of Tommy Lee Jones and Josh Brolin, as well as Javier Bardem as the fearsome but unforgettable killer Anton Chigurh, a role that won Bardem Academy Award for best supporting actor.

McCarthy’s attention turned away from the American West for 2006’s “The Road.” The book, dedicated to his then-young son – he had by then divorced and remarried again – was conceived on a trip to El Paso, Texas, he told Winfrey, as he looked out the hotel window one night.

“I just had this image of these fires up on the hill and everything being laid waste, and I thought a lot about my little boy,” he said, and wrote a couple pages. Revisiting the idea several years later, he realized those pages were the beginning of a book about a man and his son traveling through that ashen landscape while staving off the threat of cannibals.

The book wrote itself, he said, in a few weeks’ time.

The ensuing years were quiet ones, with little in the way of new material. By this time, McCarthy was spending much of his time at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, an independent research group of mostly scientists where he eventually became a lifetime trustee.

McCarthy, whose interest in the sciences was well-documented, enjoyed the company of the physicists, biologists and geologists at the institute, and it was there he was often seen writing on his Olivetti typewriter, working on his next novels, “The Passenger” and “Stella Maris,” released just six weeks apart in 2022.

The books dealt with the same story from different perspectives and featured a female main character as McCarthy’s dearth of well-developed women protagonists in his writing had long been a point of criticism. After being married three times, he told Oprah, “I don’t pretend to understand women.”

But he alluded to the twin novels and their story’s female protagonist in an interview with the Wall Street Journal in 2009, saying, “I was planning on writing about a woman for 50 years. I will never be competent enough to do so, but at some point you have to try.”

As for the lavish amounts of violence in his work, McCarthy told Vanity Fair in 2005 he didn’t know what resonated with him about that theme, only that he felt death was the principal motif at the heart of all our lives.

“Death is the major issue in the world. For you, for me, for all of us,” he said. “It just is. To not be able to talk about it is very odd.”

CNN’s Justin Lear contributed to this report.