A collection of British royal portraits, some of which have never been shown outside the UK, has gone on display at a US museum.

The exhibition, which opened Sunday at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, charts how the royal family has been depicted over the last five centuries – from Tudor portraits to recent photographs of Prince William and Prince Harry.

The survey of 150 images and objects was created in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery in London, which lent a large number of the works on display, according to the Houston museum’s chair of conservation, David Bomford.

“The monarchs are the history of the country, and what they achieved – or what they failed to achieve – is the story of the nation,” said Bomford, who co-curated the exhibition, in a phone interview.

“(The exhibition is) about character and personality, and what these monarchs were like as human beings. We’re trying to cover the personal, the political and the historical.”

From Tudors to Windsors

The exhibition begins with the House of Tudor in the late 15th century, a period in which the monarchy’s modern portrait tradition was born.

“Before that, royal portraits were not realistic, they were just generic depictions of majesty,” Bomford said. “But with the Tudors we begin to get accurate portraits – actual likenesses of real people.”

Accurate perhaps, but still subject to exaggeration. Among the exhibition’s early images is an iconic painting of Henry VIII, by the renowned German artist Hans Holbein the Younger, in which the king’s physical presence and intimidating expression are deliberate projections of power. Such images were created in the knowledge that they would be be copied and distributed around the land.

Portrayals of Henry’s daughter, Elizabeth I, present a comparable, though altogether different form of propaganda: one that reinforced the idea of her as a “Virgin Queen.”

“She never married a person – she married the country,” Bomford said. “And so she’s depicted in white clothing because she’s the bride of her nation. There’s a huge amount of propaganda going on.”

Changing depictions

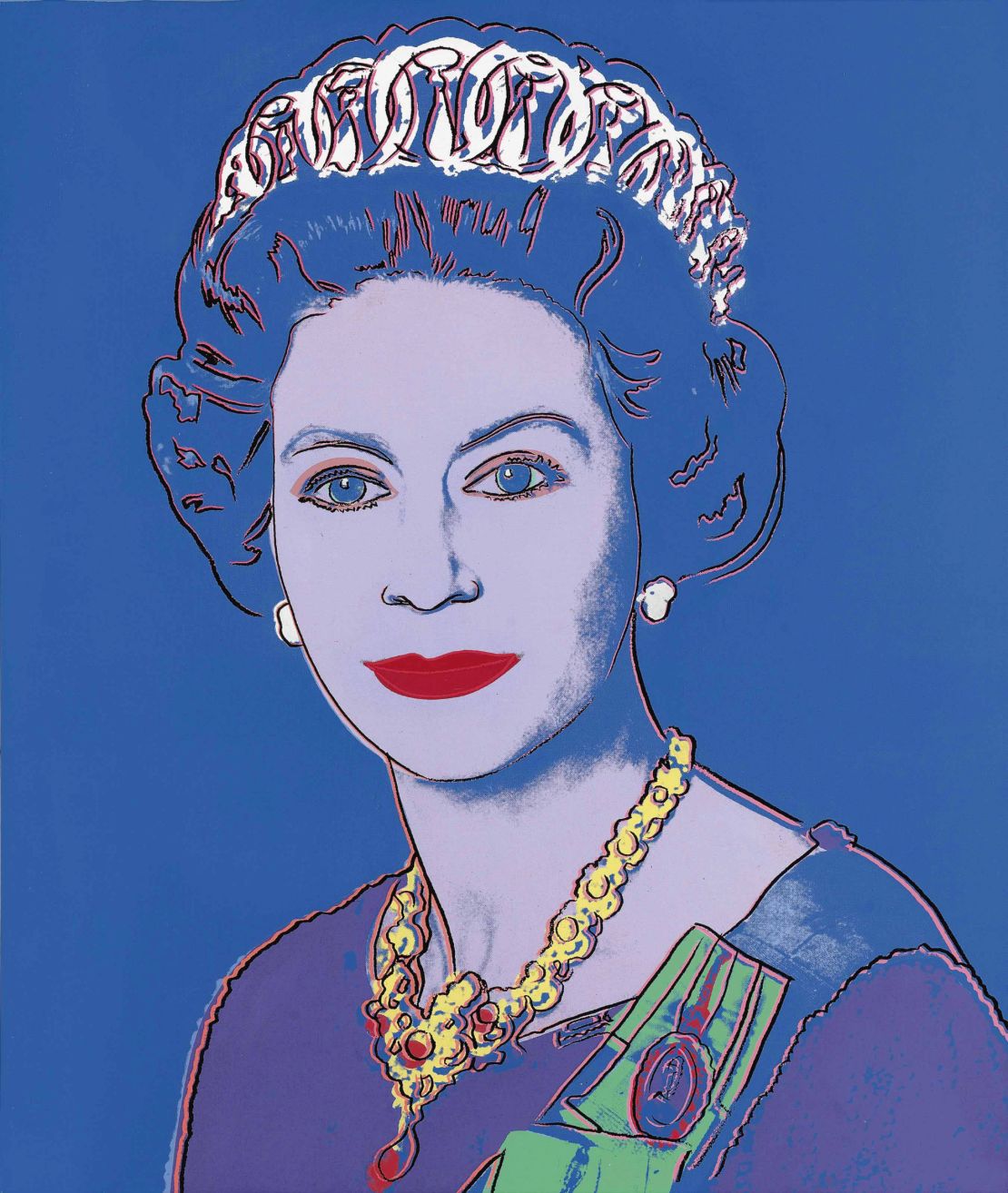

Although many of the pictures on display were commissioned and released by the royal houses of their day, the Houston exhibition also includes independent artworks, like Andy Warhol’s pop-art depiction of Queen Elizabeth II.

Their inclusion is a reminder that monarchs, princes and princesses no longer enjoy a monopoly over how they are portrayed.

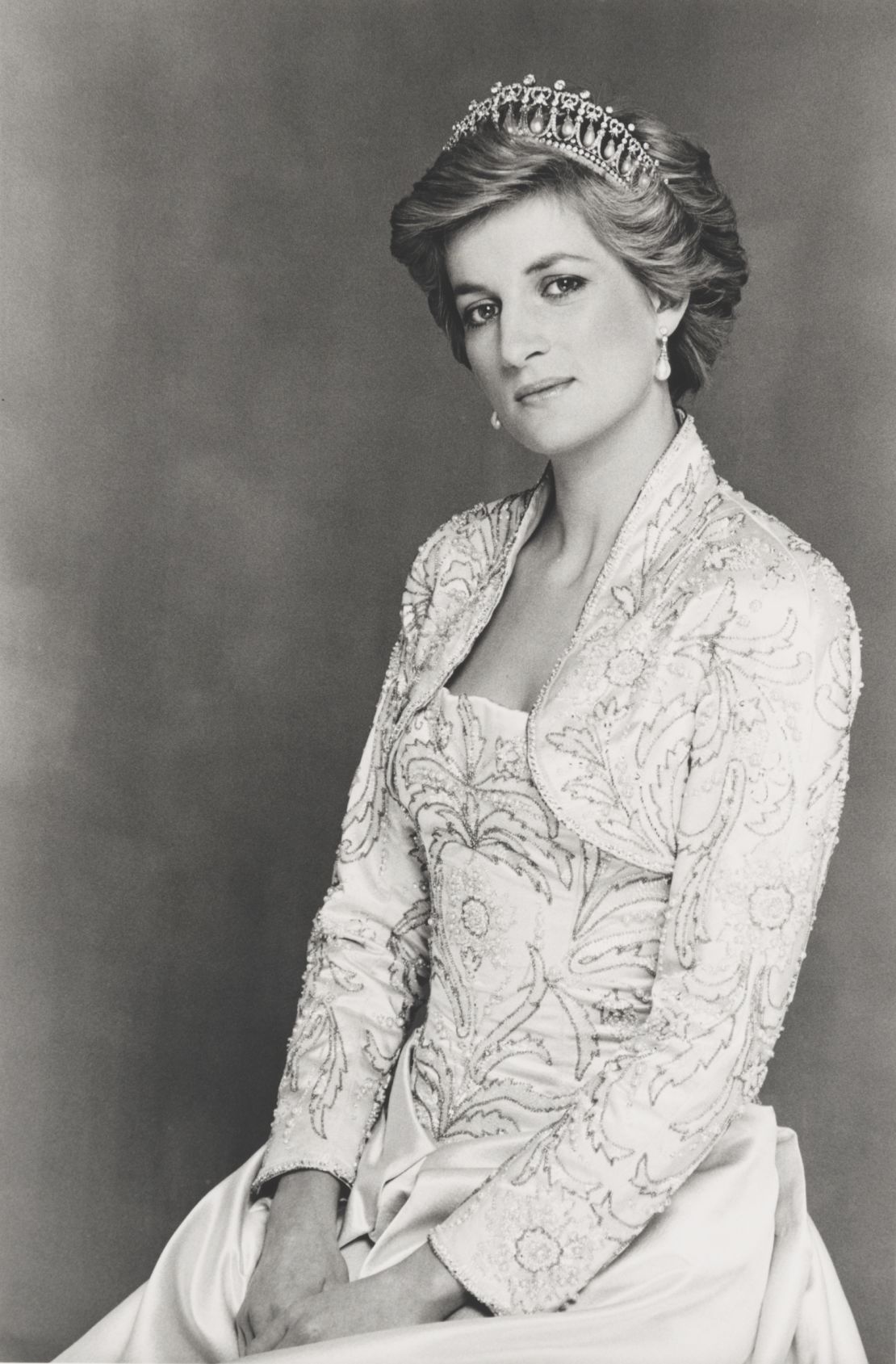

This process began, according to Bomford, with the invention of photography, which left less room for artists’ imaginations. But these photo portraits nonetheless offer insight into the times and are illustrative of how royalty wanted to be publicly received.

“The family of Queen Victoria and (her husband) Prince Albert was the first royal family that was recorded in photographs, and Albert encouraged the taking of informal photographs,” he said.

“But he wanted to show that they were just like any other family in the country, a sort of middle class concept of a family, and he deliberately manipulated the photographs – or what they recorded – to give this impression.”

Photography dominates the modern portion of the exhibition, which includes images of Edward VII, George V and Edward VIII, who abdicated in 1936. A recent photo of Queen Elizabeth II by Annie Leibovitz, and an iconic image of Princess Diana by British photographer Terence Donovan, also feature in the show.

Yet, these too should be considered in the context of how and why they were created.

“All royal portraits (are propaganda) to some extent,” Bomford added.

“Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits from Holbein to Warhol” is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, until Jan. 27, 2019.