For years, Chinese artist Badiucao has operated anonymously, wearing a mask whenever he appears in public. But now, on the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown, he has revealed his face for the very first time.

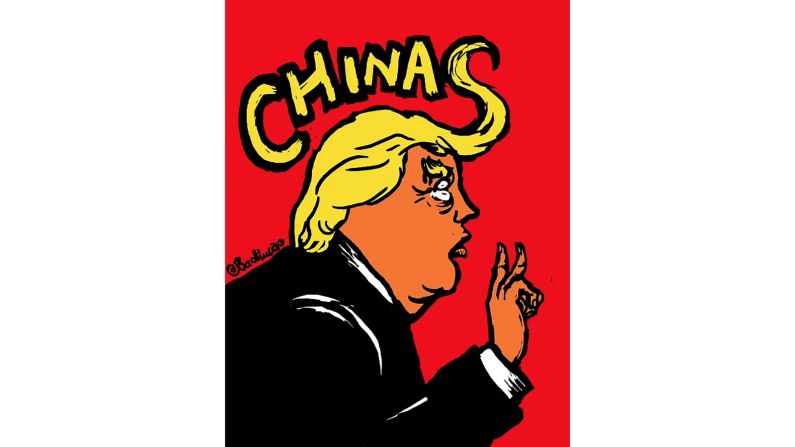

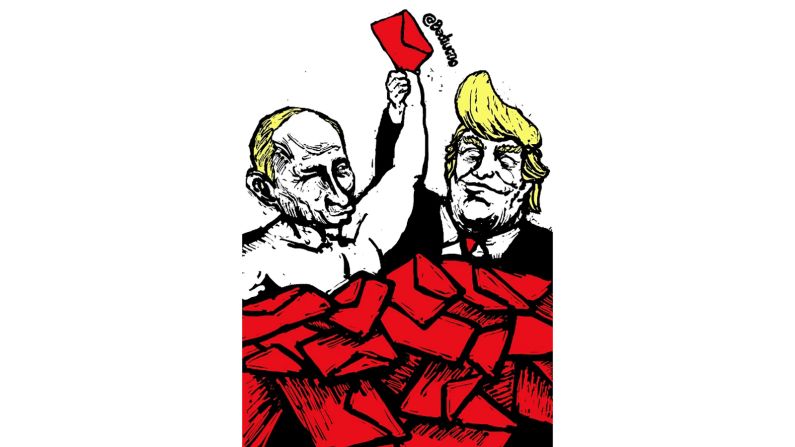

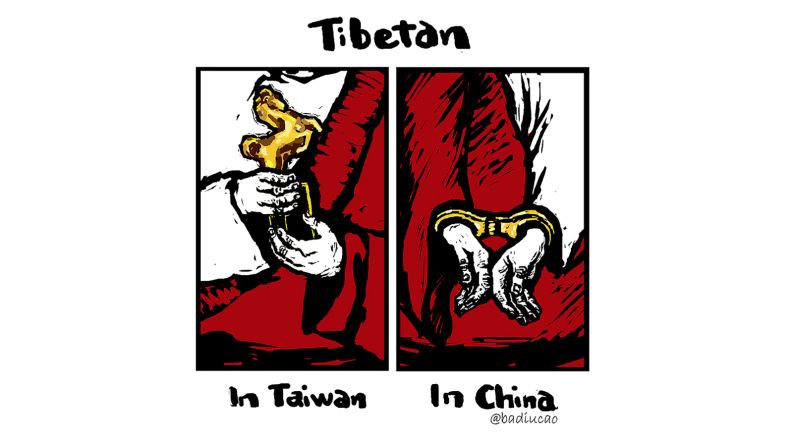

Badiucao’s name is a pseudonym adopted years ago, when he began posting caustic political cartoons lampooning the Chinese Communist Party online. He was quickly banned from Chinese social media and forced to operate outside the Great Firewall, China’s vast online censorship apparatus.

In 2009, Badiucao moved to Australia, where he has since become a citizen, renouncing his Chinese passport. But even then, he did not reveal his identity. Like the UK-based graffiti artist Banksy, he operated in the shadows, carrying out most of his work online or on the streets, and only appearing at exhibitions in heavy disguise.

During the filming of a documentary about his work – which aired Tuesday night on Australian television – Badiucao and director Danny Ben-Moshe initially went to extreme measures to maintain this secrecy. At home in Melbourne and during a year working with world famous Chinese artist Ai Weiwei in Berlin, Ben-Moshe filmed Badiucao from behind, or in disguise, taking care to avoid anything that could be used by the Chinese authorities to identify him.

“Most of the shots were of my back, avoiding showing the shape of my body,” Badiucao told CNN in a phone interview. “We were also aware of showing my fingerprints or the shape of my ear. AI technology has evolved so much that I was worried even a bit of my body could compromise my identity.”

Badiucao's political cartoons

As he reached the end of the process however, Badiucao realized that his hard fought anonymity no longer offered the protection it once did. In November last year, he was forced to pull out of a Hong Kong show at the last minute, amid concerns for his safety.

“My identity had been compromised,” he said. “The choice is clear: I either disappear or I step out and confront (the Chinese government) face-to-face.”

The documentary shows Badiucao receiving news that members of his family in China had been contacted by the country’s authorities. He wrestles with the decision to cancel his Hong Kong exhibition, with organizers, including Hong Kong Free Press and Reporters Without Borders, eventually taking the decision out of Badiucao’s hands, fearing for the safety of his family and show attendees.

In one of the last shots of the film, the camera pans out to show Badiucao unmasked. His hair is cropped short, and he wears round glasses and a goatee.

“They know me now, this is me,” he says, as the camera zooms in on his face before fading to black.

Speaking to CNN about his decision to show himself, Badiucao said he didn’t think continued silence “would bring me any protection or peace.”

“This is my new reality,” he added.

New reality

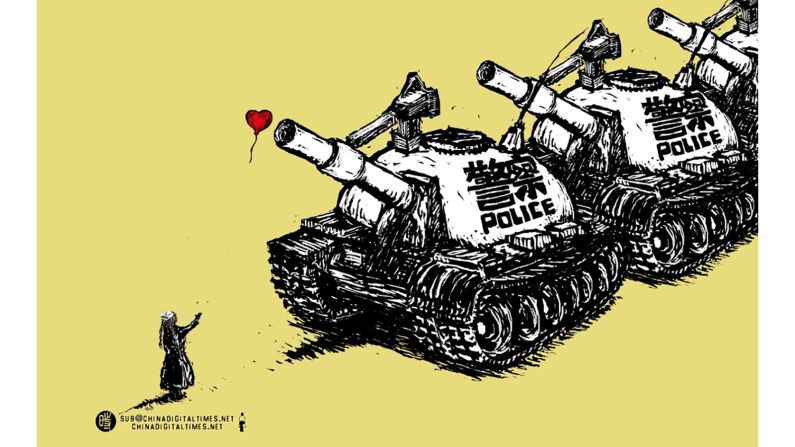

The documentary, “China’s Artful Dissident,” aired on June 4, the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, in which hundreds of pro-democracy protesters were killed by soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army.

June 4 is always one of the most sensitive times in the Chinese calendar, as the authorities seek to suppress any commemoration of the crackdown.

Badiucao has always made Tiananmen a key part of his work, staging recreations of the iconic “Tank Man” photo in Australian cities, and producing numerous artworks around the topic.

Now he has tied the date indelibly to his identity.

“I want to choose the brave way,” Badiucao said. “We need dumb people to step out and see if the world is still hopeful. I’m willing to be that dumb person.”

What remains to be seen is how the Chinese authorities react to the revelation. Badiucao’s parents also live in Australia, and he is not in touch with other family members still in China.

He hopes that, by publicly revealing his identity, he can reduce pressure on people no longer in any position to influence him. A public profile may also help protect him against any future retaliation, he said.

“Because I will be monitored by media and human rights NGOs, in that way I will be safer,” he said. “In that case, I don’t think being public is a bad thing.”

The artist is, however, concerned that he may become a target for what he described as “ultranationalists” in China, who may seen his actions as a challenge to Beijing.

Moving forward

Whatever the reaction, Badiucao’s decision is now made, and his face has been broadcast worldwide.

While the circumstances around the decision have been uncomfortable and stressful, the artist expressed a sense of relief about going public. Following the cancellation of his Hong Kong show, he went quiet for almost six months, worrying in private about what to do.

“Showing my face (is) definitely a release for me,” he said. “I don’t need to live a double identity life anymore, it also removes barriers (in) my social life, and makes it easier to develop my career as an artist.”

One thing he won’t be changing is his name. Badiucao – or Badi for short – has gotten so used to the moniker, once adopted as a deliberate nonsense term to hide his identity, that it feels more familiar than the one he was given by his parents.

“I have been Badiucao for at least six years,” he said. “I’m not used to being referred to by my real name.”