Story highlights

Eritrea's capital Asmara is home to one of the world's best collections of futurist architecture.

The is bidding to become the nation's first UNESCO World Heritage site.

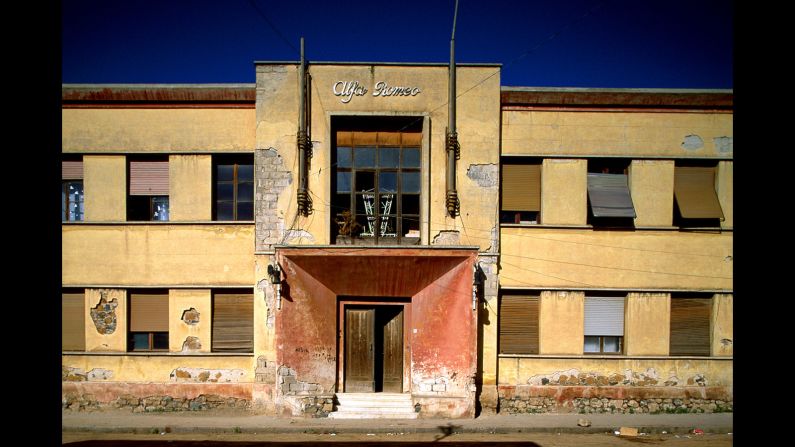

Once a sleepy corner of the Italian Empire, Eritrea’s capital Asmara is home to one of the world’s best collections of futurist architecture. Now, the city is bidding to become the nation’s first UNESCO World Heritage site.

Asmara certainly deserves the distinction; its architecture – built in the modern era and informed by the school of futurism – is some of the most beautifully preserved in the world. And the city owes it all to Fascism.

A Futurist haven

Italy developed an urban plan for the capital of its colony as early as 1913, though it was under Mussolini’s fascist government that modern architects built the city into what it is today, earning it the nickname “La Piccola Roma.”

“There was a very intense period of architectural development from 1935-1941,” notes Edward Dension, a lecturer at the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL).

Everything from cinemas to cafes to prisons were constructed in rapid succession, an entire city popping up inland from the Red Sea. Little was left untouched my modernist hands – the Fiat Tagliero, Asmara’s most iconic construct, is on paper one of its most mundane: a service station.

“It’s that combination of urban planning and modernist architecture that makes Asmara so interesting,” Dension argues, “because it was a whole city, not part of a city, like Casablanca, or Tel Aviv.” As for why, he is uncertain.

“Were [the architects] there to champion fascism, or colonialism, or were they there to run away from it and just get on with what they liked to do, which was design buildings? We still don’t know enough about that, but I suspect it’s the latter.”

“By the 1930s [futurism] fell out of favor with the fascist government of Italy,” he explains. “And so one thinks, those who espoused futurism and wanted to articulate it in architectural form, could do so only in the colonies.”

What’s independence got to do with it?

Africa's amazing architecture: Do these buildings represent freedom?

Italy’s loss was Eritrea’s gain, but in the years since it has been an uneasy road for the East Africa nation. From Italian colony to British administration to Ethiopian federation, the “process from colonialism to independence was uniquely protracted” for Eritrea, says Dension. And it is arguably why Asmara is in such good condition.

Dension suggests that Eritreans “probably view their colonial architecture a lot differently than say Libya does with Tripoli, or Somalia does with Mogadishu, where some of the colonial buildings were deliberately destroyed, or disregarded… which a newly-independent country would want to do away with.” Because of the lengthy path to independence, “those strong feelings against the colonial ruler were perhaps not quite so strong when independence arrived.”

Proud heritage

Eritreans today maintain a close relationship with their modernist heritage, spurred on by an unlikely source: ex-prison inmates.

Caserma Mussolini, a military barracks that served as a detention center during colonial rule, was due to be razed in 1996 and replaced with a German-designed high-rise.

“It was the former inmates of that prison that said ‘You can’t destroy this building, it’s part of our heritage’,” Dension explains. “It was the inmates who really started focusing Eritrean minds, and started them thinking ‘What do these buildings actually mean to us?’”

A World Bank-funded project, the Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project, ran between 2001 and 2007 and started preservation work, an initiative continued by the Asmara Heritage Project (AHP), established in 2014.

Dension has played a part in both teams, the latter under coordinator Medhanie Teklemariam, and says that on February 1 the AHP submitted Asmara for consideration as a UNESCO World Heritage site – what would be a first for Eritrea.

“Africa is underrepresented on the UNESCO World Heritage list, and also in modernist history,” he argues.

“Our understanding of modernism is very much framed by a Western-centric, Euro-centric perspective. It does reveal a problem in the way that we understand Modernism and the way we understand colonial history. Asmara’s bid is just one of many that will increasingly try to redress this imbalance.”