Architects are – sometimes to their dismay – confined by the limits of engineering. In turn, engineers are confined by the limits of physics.

So perhaps the art world is better placed to push the boundaries of architectural imagination. Now, a new breed of digital artists is combining photography with image manipulation techniques to bend, twist and distort cities to their will.

Their illusory worlds might not be strictly possible, but they can offer new commentary on our cities, forcing us to reassess buildings and urban spaces in the process.

Making art from architecture

Spanish artist and photographer Victor Enrich began transforming architectural photos during a trip to Riga, Latvia. In what would become the first image of a series called “City Portraits,” he photographed one of the city’s road bridges before sending the structure soaring into the sky at a 90-degree angle.

The artists bending cities to their will

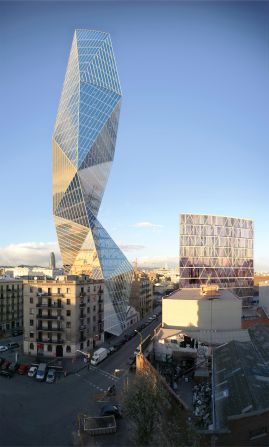

Other pictures in the “City Portraits” series saw Enrich twisting tower blocks into fantastical shapes, attaching stories-high slides onto residential blocks and creating impossibly top-heavy skyscrapers that appear to stand without structural support.

Having spent more than a decade as a CG artist and visualizer for architecture firms in Barcelona, Enrich was already familiar with the 3D modeling software needed to distort his pictures.

“I thought that it was time to start using the techniques that I’d been learning, but on the streets,” he said in a phone interview. “So I quit (my job) and began to experiment with the same tools, without any specific goal other than to explore the possibilities.”

Once he has photographed a building, Enrich digitally maps the perspective and the building’s architectural lines. After bending or otherwise altering the structure, he must painstakingly apply texture, color and shading to make the changes appear as realistic as possible.

A single image can be completed in three weeks, though his 2013 project “NHDK” – in which Enrich manipulated a single photo of Munich hotel into a series of 88 different shapes – took over eight months to finish.

“I had to model everything – not only what I was seeing, but everything that was hidden (by the building),” he said. “Imagine modeling the roof of a skyscraper that you don’t have access to, and the only thing you have is a satellite image which is blurred and pixelated.”

The tradition of architectural painting has, since its popularization during the Renaissance, focused on faithfully replicating buildings or creating idealized visions of cities. But while Enrich’s art is quintessentially modern – in both method and outcome – he sees links between his work and that of conventional artists.

“One of the things I really enjoy doing is tracing – like the Old Masters,” he said, referring to the disputed theory that Renaissance painters first traced out pictures using a lens. “They weren’t memorizing what they were seeing and then transferring it – everything was being projected onto a surface and then painted.

“I mostly do the same thing, but instead of doing it in real life, I do it in a digital environment.”

Works of ‘architectural fiction’

This type of urban digital art is rarely discussed in terms of being an explicit genre. But if it were, it might include anything from Laurent Chehere’s “flying houses” to the photomontages of Filip Dujardin, who builds impossible structures using collaged images of existing buildings.

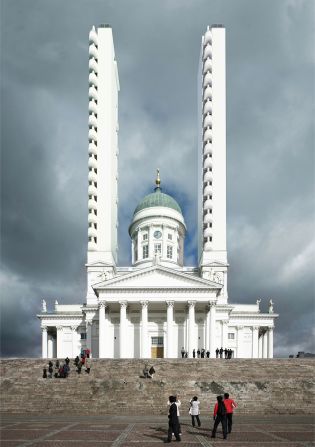

Referring to the style as “architectural fiction,” Brussels-based artist Xavier Delory sees commonalities and differences running through all of their work.

“In recent years, there have been quite a few artists working on images of architecture using similar computer tools,” he said in an email interview.

“But with conceptual and formal approaches that can be quite different. I think these artistic approaches make architecture more popular with neophytes.”

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Delory often focuses on the impact of urban decay on buildings. In one of his best-known series, “Pilgrimage Along Modernity,” he modified pictures of famous modernist buildings – including Le Corbusier’s iconic Villa Savoye – to appear vandalized, smashed or covered in graffiti.

“With (the) series, I question the fragility of history and the choice of societies to grant importance, or not, to the preservation of the creations from the past,” Delory said. “But also, I am fascinated by the aesthetics of ruins and their beauty. I like this state because it shifts architecture towards sculpture.”

Changing contexts

The possibilities of the genre are wide-ranging. Having spent over three years twisting and bending structures, Enrich now focuses on a process he calls “dislocating” buildings – transporting them to entirely new surroundings. The resulting photos explore how changing a structure’s context can alter our perception of it.

In 2016, he created a series of images that placed Frank Lloyd Wright’s celebrated Guggenheim building in various new locations. One sees the museum attached to the side of central London’s “Cheesegrater” skyscraper, a critique of money’s impact on art. Another transports the modernist masterpiece to a run-down part of Colombia’s capital, Bogotá, drawing attention to the differences North and South America.

Enrich has also re-imagined the White House in solid gold and set beneath a Broadway-style sign bearing the word “Trump.” His creation was then superimposed onto a desert and enclosed by a secured perimeter fence.

But despite his increasingly provocative output, the photographer has retained the mischievousness sense of fun seen in his earlier work.

“Maybe what I’m trying to do is invite people to play with me,” Enrich said, “to invite people into my world.”