Editor’s Note: Aric Chen is curator-at-large at M+, a new museum of visual culture under construction in Hong Kong, and professor of practice at Tongji University’s College of Design & Innovation in Shanghai.

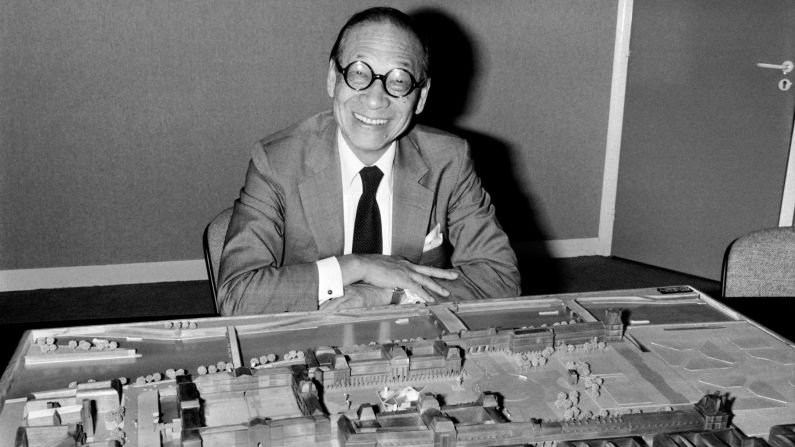

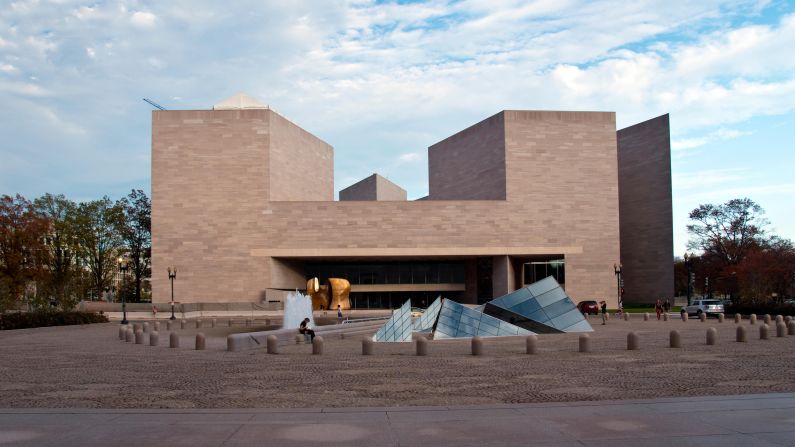

I.M. Pei, who died Thursday at the age of 102, was an architect of singular vision. One of the great figures of 20th century modernism, he was perhaps best known for his powerful use of geometry. He employed it to create forms and spaces of exquisite refinement, from his glass pyramid at the Louvre in Paris to the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

He brought to his work the notion that good architecture served a higher civic purpose. But at the same time, Pei was an architect of multiple dimensions.

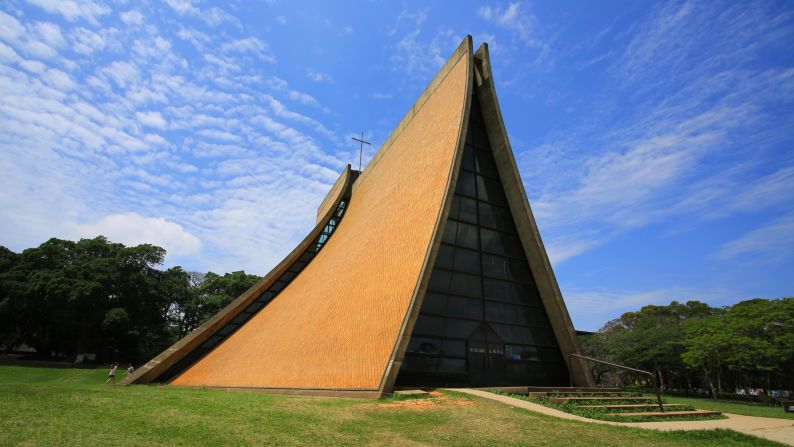

He did not plan to stay in the US when he arrived from China to study in 1935. His thesis projects at MIT and Harvard – a mobile media and recreation center for rural China and a modern art museum for Shanghai, respectively – signaled his intention to return to his native country.

Nevertheless, war and upheaval got in the way. Pei and his wife Eileen Loo, a Harvard classmate, would call New York home for the rest of their lives.

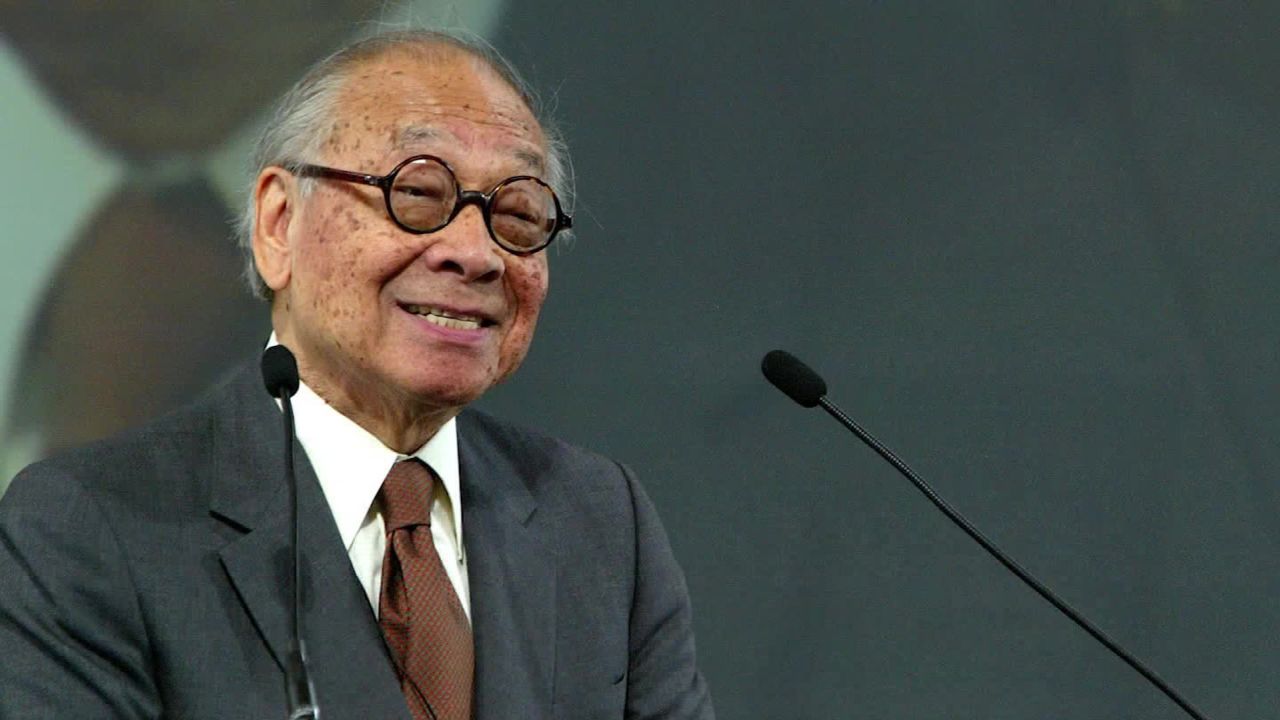

Famously charming, with dapper style and a beaming smile, Pei easily straddled, and found clients in, the worlds of both culture and commerce. However, success did not always come easy.

Celebrating the life and work of I.M. Pei

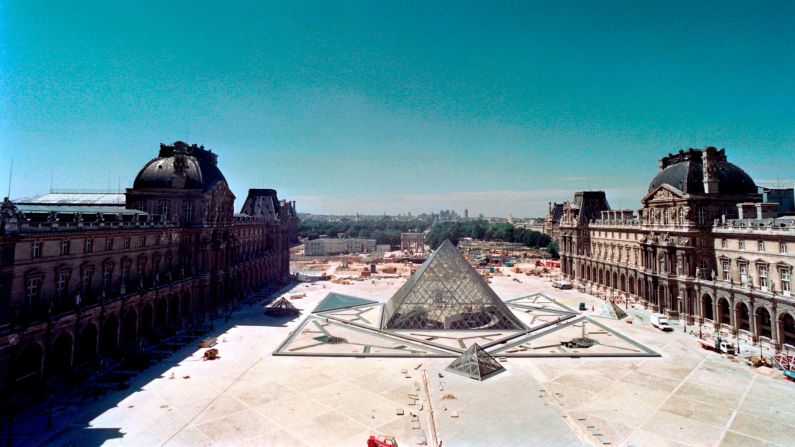

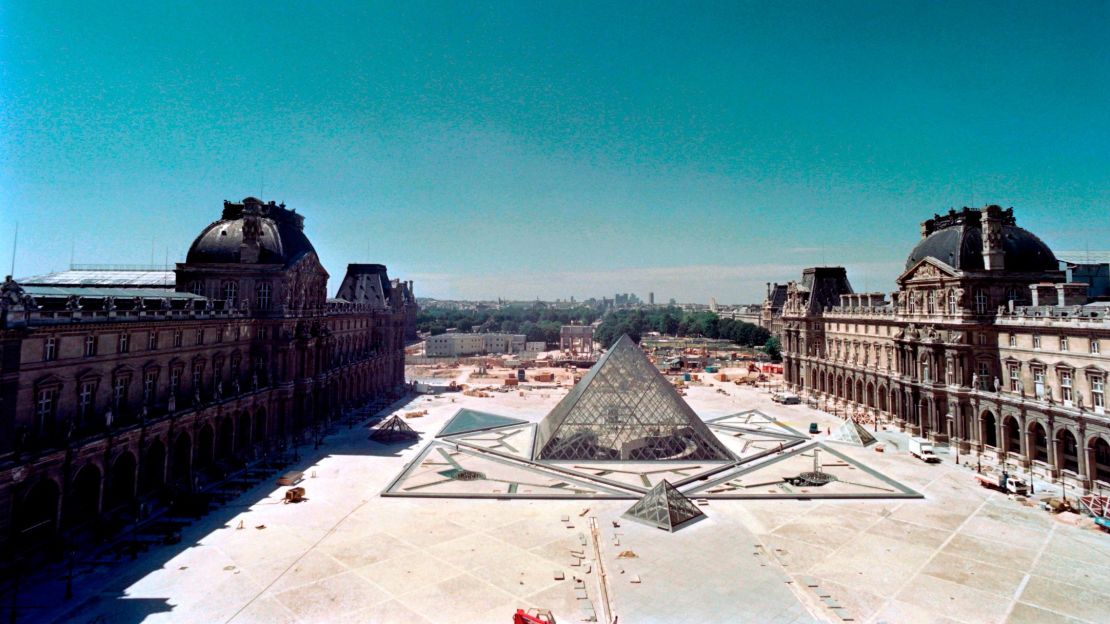

Before seducing Paris, he utterly scandalized the city with his proposal for a glass pyramid at the Louvre, a then-radical proposal for a site seen by many as representing the soul of France. (And by a Chinese-American architect, no less!) His John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston was, for years, mired in controversy, and he considered the construction of the Fragrant Hill Hotel outside Beijing – one of the first buildings designed by an international architect in reform-era China – to be one of the most painful experiences of his professional life.

But with these projects, and others, Pei sought timelessness and, at this point, it seems fair to say he achieved it.

He did so, often, by forging his own path. A student of the revered Bauhaus architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer while at Harvard, Pei broke with his profession’s gentile conventions when, in the late 1940s, he dared to start his career working for a real estate developer: the brash, larger-than-life William Zeckendorf.

Along with a formidable assortment of colleagues and collaborators, he also pioneered new construction techniques, especially in concrete. Later in life, with buildings like the Miho Museum outside Kyoto and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, he deftly translated his modernist vocabulary into different cultural contexts, and perhaps nowhere more so than in China.

Pei returned to China for the first time in 1974 as part of a delegation of American architects. Soon thereafter, officials asked Pei to design a modern high-rise hotel in central Beijing – an aspirational gesture for the then-impoverished nation.

Concerned about the effect such a building would have on the capital’s historic character, Pei refused. Instead, he selected a site on the city’s wooded outskirts and produced a low-rise complex, the Fragrant Hill Hotel, whose white walls and relationship with its landscape were inspired by the classical architecture and gardens of Suzhou, the Pei family’s ancestral home. (There, the architect would later design perhaps his best project in the country, the Suzhou Museum.)

Pei always referred to himself as an American architect, but he never forgot that he was also Chinese. Perhaps this dual sense of identity helped him operate so fluidly in multiple worlds.

I had the good fortune of meeting Pei, though only once, when he was a sprightly 95-year-old. I simply wanted an interview. But against the better judgement of his son, he insisted that we have lunch beforehand at his old haunt, the Gramercy Tavern in Manhattan.

Lunch with Pei, I learned, always meant plenty of good wine, and this time was no exception. The interview suffered as a result, but, true to Pei’s reputation, it was a pleasure nonetheless.