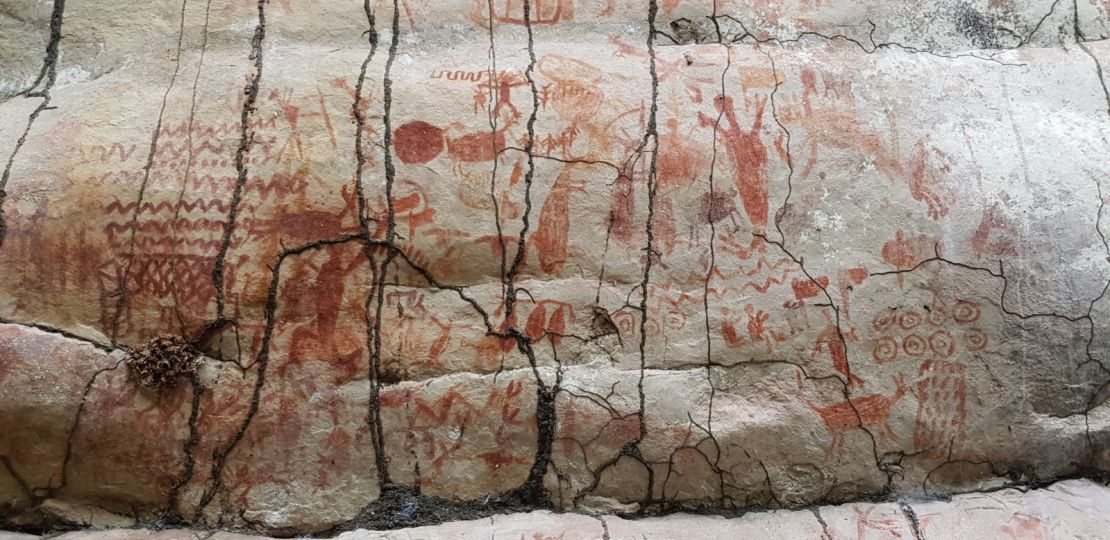

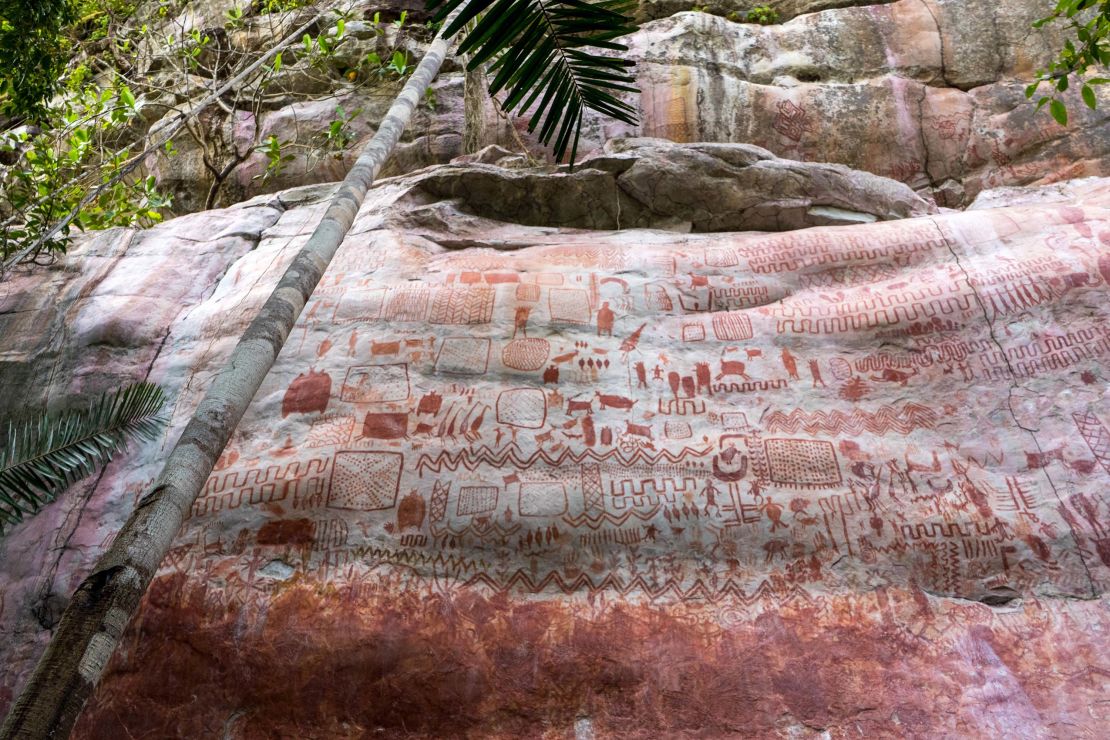

Thousands of rock art pictures depicting huge Ice Age creatures such as mastodons have been revealed by researchers in the Amazon rainforest.

The paintings were probably made around 11,800 to 12,600 years ago, according to a press release from researchers at Britain’s University of Exeter.

The paintings are set over three different rock shelters, with the largest, known as Cerro Azul, home to 12 panels and thousands of individual pictographs.

Located in the Serranía La Lindosa in modern-day Colombia, the rock art shows how the earliest human inhabitants of the area would have coexisted with Ice Age megafauna, with pictures showing what appear to be giant sloths, mastodons, camelids, horses and three-toed ungulates with trunks.

“These really are incredible images, produced by the earliest people to live in western Amazonia,” said Mark Robinson, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter.

“The paintings give a vivid and exciting glimpse in to the lives of these communities. It is unbelievable to us today to think they lived among, and hunted, giant herbivores, some which were the size of a small car.”

Other pictures show human figures, geometric shapes and hunting scenes, as well as animals such as deer, tapirs, alligators, bats, monkeys, turtles, serpents and porcupines.

The red paintings, made using pigments extracted from scraped ocher, make up one of the largest collections of rock art in South America.

At the time when the drawings were made, the Amazon was changing from a patchwork of savannahs, tropical forest and thorny scrub into the broad-leaf tropical forest we know today.

The artists would have used fire to exfoliate the rock and make flat surfaces on which to paint, experts say. While the paintings are exposed to the elements, they are protected by overhanging rock, which means they remain in better condition than other rock art found in the Amazon.

Some of them were painted so high up on the rock that “special ladders crafted from forest resources would have been needed” to create them, according to the press release.

The people who painted the pictures were hunter-gatherers who ate palm fruit and tree fruits, as well as fishing in the nearby river for piranha and alligators. Bones and plant remains also reveal they ate snakes, frogs, armadillos and rodents, including paca and capybara.

Researchers on the project are working to find out when humans first settled in the Amazon region, and how their presence affected biodiversity.

José Iriarte, Professor of Archaeology at Exeter, told CNN that the findings are an initial stage in a project that will run for five years.

One of the immediate aims is to document all of the rock art in the area, and work out what other animals are depicted, he said.

“These rock paintings are spectacular evidence of how humans reconstructed the land, and how they hunted, farmed and fished,” Iriarte said in the press release.

“It is likely art was a powerful part of culture and a way for people to connect socially. The pictures show how people would have lived amongst giant, now extinct, animals, which they hunted.”

Iriarte was impressed by the realism of the paintings, which were produced during a rare window in which early humans lived alongside megafauna.

“The level of observation of the fauna was incredible,” he said.

The rock paintings feature in a new TV series, “Jungle Mystery: Lost Kingdoms of the Amazon,” on the UK’s Channel 4, and the findings are also described in an article in the journal Quaternary International.

Robinson and Iriarte worked on the project alongside Javier Aceituno of the Universidad de Antioquia in Medellin, Colombia and Gaspar Morcote-Rios of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogota.

Communities in the local area knew of the rock paintings, and helped researchers document them in the wake of the 2016 peace deal between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrilla group, which disarmed after 52 years of conflict. Researchers worked at the site in 2017 and 2018.