Editor’s Note: Craigh Barboza teaches film journalism at New York University and writes about race, entertainment and culture.

Following the wave of demonstrations sparked by the killing of George Floyd, many of us have been thinking about the history of race in America, and the ongoing narrative of police violence. We are all looking for resources to help better understand the moment.

Each of the movies below offers a different perspective on how African Americans have contended with white authority over the decades and centuries. They both speak to and echo what is happening now.

The films range from underground classics to big-studio productions, all of which put a human face on timely and difficult social justice issues that have shifted the conversation on racial equality in America in a way that only movies can do.

If you’ve seen the films on this list, you can rewatch them in a new light. And if it’s your first time, you might recognize something that resonates with the hundreds of Black Lives Matter and anti-racism protests that have erupted worldwide calling for wide-reaching reform.

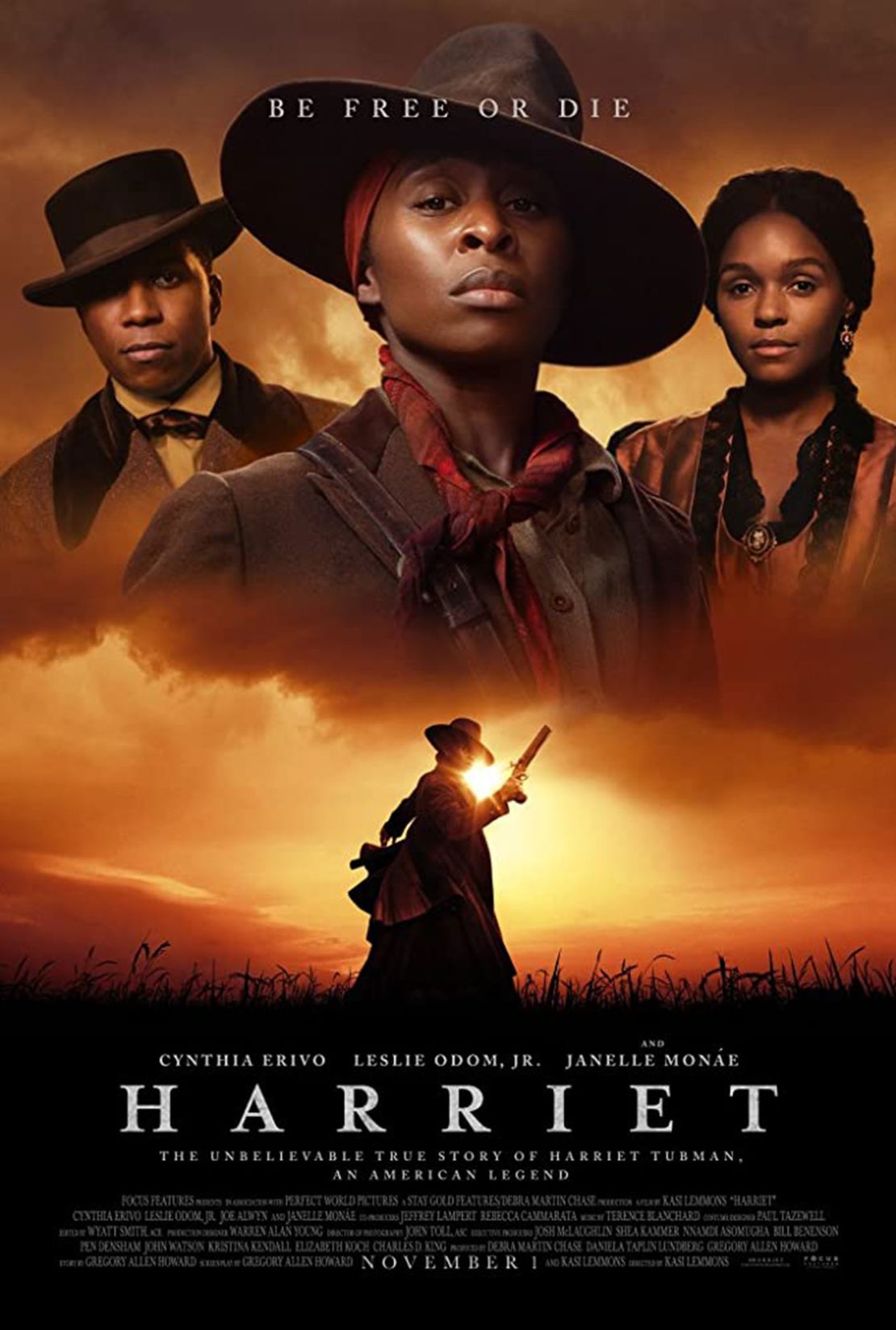

“Harriet” (2019)

Kasi Lemmons’ recent biopic portrays the famed abolitionist Harriet Tubman (Cynthia Erivo) as a young, gun-toting heroine prepared to die for the freedom of her people. Starting out in 1849, “Harriet” explores the monstrous institution of slavery and how it seeped into American law enforcement in the form of marshals and paid trackers – sometimes seen as glorified slave catchers.

“What you see in the movie are these armed posses that are after black people,” said Donald Bogle, the film historian and author of “Hollywood Black,” via email.

“There’s that sequence on the bridge when Harriet is cornered, after an escape, and she says, ‘I’m going to be free or die’ and jumps into the river. I think we can draw a connection to what’s happening today and a system of pursuers, these violent white men who, in some ways, are sanctioned to murder us.”

Erivo’s breakout performance as Tubman (she was a double-Oscar nominee last year for best actress and original song) is worth the price of streaming alone. After making it to Philadelphia, she joins the Underground Railroad, where she becomes its most famous conductor. We learn about the prophetic visions that helped her lead approximately 70 enslaved people to freedom, as well as Tubman’s command of a black army that freed 150 more in the Combahee River Raid.

“Harriet” underscores the important role African American women have played in history, and how they continue to suffer discrimination and persecution. “We’ve had these instances, like Sandra Bland, who was stopped by the cops for something so minor and, we have it on film – the way the cop spoke to her and she spoke back – and she was taken into custody and ended up dead,” Bogle said. “There’s this idea that this whole system violates African American men but it can do this to African American women as well.”

“Rosewood” (1997)

John Singleton’s “Rosewood” tells the true story of how, in 1923, a prosperous black town in Florida was burned to the ground. The fuse was lit by a white woman (played by Catherine Kellner) who falsely claimed that she was raped by a black stranger – a story whipped up to explain the bruises inflicted by her extramarital lover. Throw in some trumped-up talk of a race riot by one of the local officials and it’s not long before a group of Klansmen are swarming the town in search of a mysterious black war veteran (played by Ving Rhames).

The result is a week-long massacre of torture, shootings and lynchings that Singleton shows in grisly ways on a scale that had never been done before in movies depicting slavery or its legacy. Survivors, many of them children, fled through the nearby swamps. The official death toll was eight, although many believe the final number was much higher. “‘Rosewood’ effectively captured the real-life horror of racism,” said the activist and author Dr. Umar Johnson in an email. “The lynchings of thousands of African Americans, from the end of slavery in 1865 until the death of Malcolm X in 1965, shows just how inhumane White America can be.”

The film is a powerful reminder that black lives, even entire communities, can be destroyed when someone “weaponizes [their] whiteness,” as the cultural critic Roxane Gay recently put it in reference to the news last month of a white woman who called the cops on a black birder in New York’s Central Park after he asked her to leash her dog, which is the law. (The call was made on the same day that George Floyd was killed.)

“Selma” (2014)

Real change in society has often been the result of a political alliance between inside and outside forces. In addition to a citizen-based movement it’s necessary to have government operatives or, even better, leaders like Martin Luther King who can stir the people in power to change laws.

As the central figure in “Selma,” King (David Oyelowo) is a virtuoso combination of grace, intelligence, rhetorical power and persistence. In an early scene inside the Oval Office, he implores a reluctant President Lyndon Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) to push through the Voting Rights Act of 1965, intended to dismantle barriers that had been put in place to stop some black citizens from voting. Without it, he explains, African Americans would not have the same legal rights, but would continue to be murdered by white people, who would either be protected by white officials or acquitted by all-white juries. “All white,” King says, “because you can’t serve on a jury unless you’re registered to vote.” Told he’ll have to wait, King organizes a massive voting rights demonstration in the South.

The scenes in Ava DuVernay’s protest drama are played in a stately, but intimate style. The most powerful images are of the scores of activists marching peacefully through the segregated streets of Alabama. “Ava’s film reminds people that no change has ever happened in America without a movement, and struggle, and that it is never easy,” said writer-activist Kevin Powell, whose new book of essays, “When We Free The World,” is out later this month.

You can feel what it must have been like to be on the front lines – along with would-be voters (Oprah Winfrey, LaKeith Stanfield) and future Congressman John Lewis (Stephan James) – standing up to a horde of state troopers brandishing rifles, electric cattle prods and whips.

“Selma” went on to win an Oscar for best original song (“Glory” by Common and John Legend) and is the rare studio movie directed by an African American woman.

The film is set around the march on Bloody Sunday in 1965, and the maneuverings and events leading up to it, including the church bombing that killed four little girls in Birmingham, which was a major turning point in the civil rights movement.

“‘Selma’ is a case study in leadership,” added Powell. “It’s actually a blessing to have a film to point people to as a teaching tool, to root folks in history, so they understand this is not just for us now, but for those not yet born.”

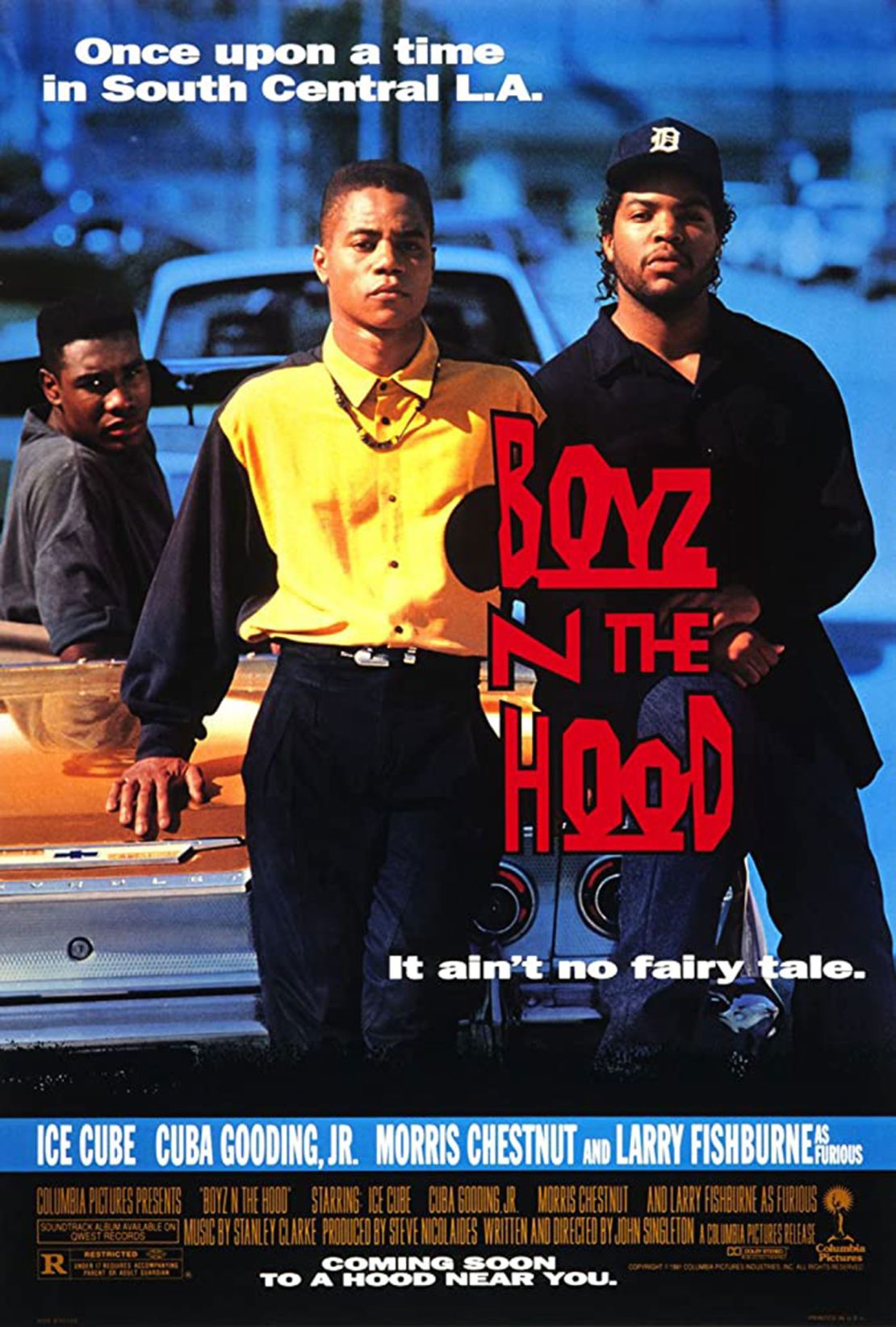

“Boyz N the Hood” (1991)

Gang violence was visible on the nightly news and MTV when this searing drama about the challenges black men face while growing up in South Central Los Angeles arrived in 1991.

“Boyz N the Hood” was by no means the first film to tackle the subject. But it had often been done poorly: for instance, when the story is told from the perspective of the cops – see “Colors.” (Better yet, don’t!) “Boyz N the Hood,” on the other hand, was notable not just for its nuanced, insider’s perspective of black life on the margins, but for who was behind the camera. John Singleton was fresh out of USC film school when he became part of a new generation of black filmmakers in Hollywood to find success with mainstream audiences.

In his semi-autobiographical debut, Singleton used the structure of a coming-of-age tale to show what it’s like to live in a world where a trip to the corner store could end in a homicide by shotgun. The film earned him two Oscar nominations, for writing and directing, and also introduced several future stars, including Cuba Gooding Jr., Regina King and Ice Cube, who had recently launched a solo rap career after parting with the gangsta rap group N.W.A.

One of the most contemptible characters in “Boyz N the Hood” is a black police officer (Jessie Lawrence Ferguson) who responds an hour late to a 9-1-1 call by the main character’s father, Furious (Larry Fishburne).

“Homeboy shows up drinking a cup of coffee,” said director Malcolm Lee, whose movies include “Undercover Brother” and the upcoming “Space Jam: A New Legacy.”

“He feels he’s better than hood Negroes because he’s in law enforcement, and thinks the world would be better if Furious had killed the intruder,” Lee said via email. “He says, ‘It’d be one less n**ga out on the streets we’d have to worry about.’”

Years later Furious’s college-bound son, Tre (Gooding), is driving home at night when he’s stopped by that same officer, who mistakes Tre for a possible gangbanger. Hot-headed and volatile, the cop draws his Smith & Wesson and threatens to blow Tre’s head off. We watch as a single tear trickles down Tre’s face. In his anguish you can sense the trauma many black people experience after encounters with the police.

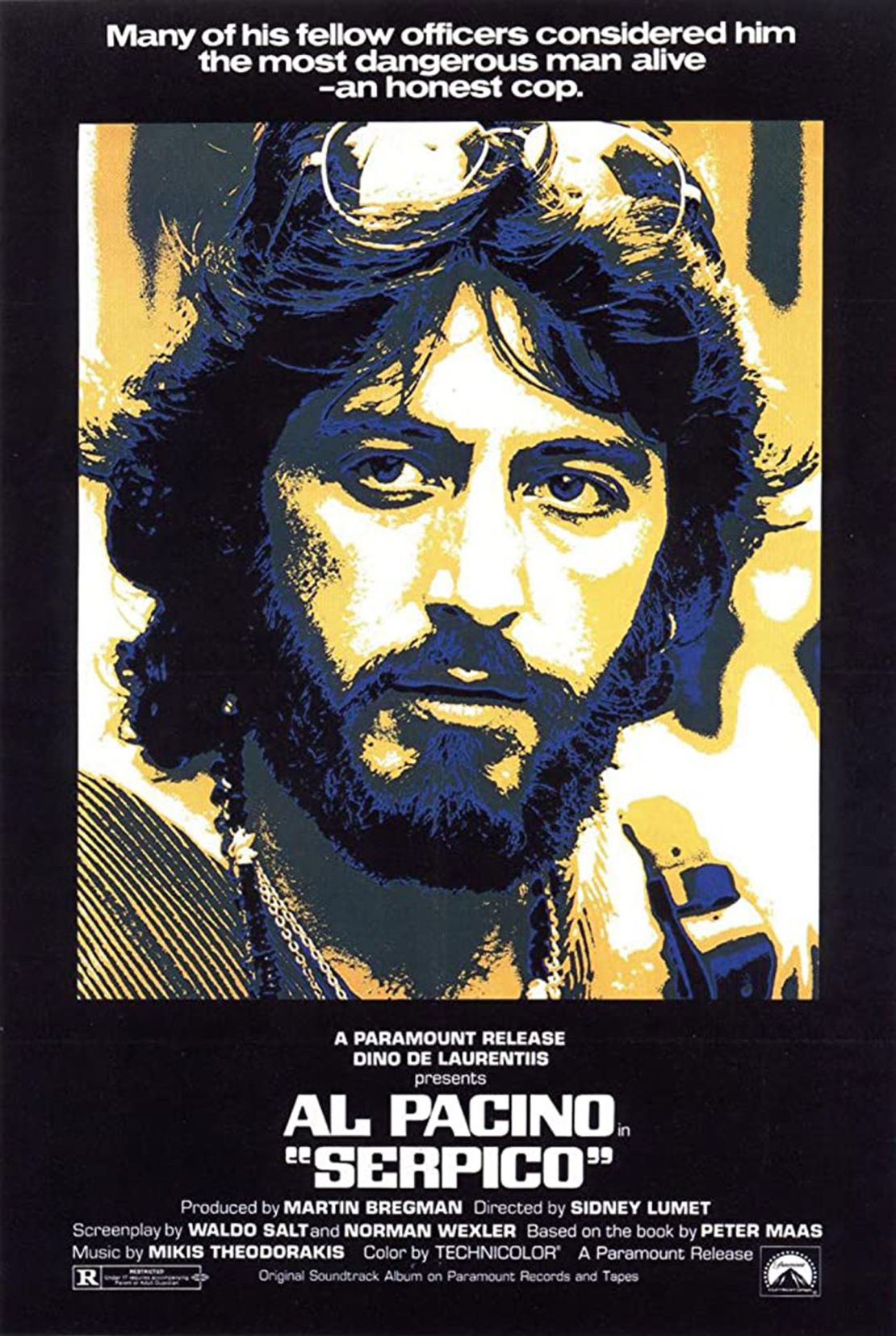

“Serpico” (1973)

Last week former President Barack Obama called on local governments in the U.S. to embrace police accountability and said that, in his view, the “vast majority” of police officers are not violent. But the fact is that good cops can sometimes find themselves ostracized if they break rank.

One of the first films to give us a realistic glimpse into life on the force was “Serpico,” with Al Pacino in the title role, an incorruptible detective with a fondness for wild disguises. The fact-based thriller not only turned Pacino into a star when it was released in 1973, it also depicted an out-of-control big-city police department where dirty, racist cops work over perps and take bribes from gamblers and drug dealers.

“Hey, Frank, you want a piece of this?” asks one cop, who’s assaulting a black suspect. “No, I’m going to fill out the police card,” Serpico replies.

“‘Serpico’ is a really powerful depiction of how hard it is to reform policing,” said Touré, the writer and host of the podcast Touré Show, featuring in-depth interviews with successful black people. “It shows how much the police will fight against those who demand more from them. The real-life Serpico risked his life to expose wrongdoing.”

At first, Serpico is persuaded, then repeatedly pressured, by fellow officers to “go along,” before he blows the whistle on graft and corruption in the department. High-ranking city officials reportedly tried to block the investigation, which blew the lid on the documented “code of silence,” or blue wall, that many precincts are accused of maintaining.

“The police don’t want to be policed!” said Touré, who believes that it is how you end up with three other officers standing by as Derek Chauvin dug his knee into George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds. “It rips at the core of (the police’s) culture.”

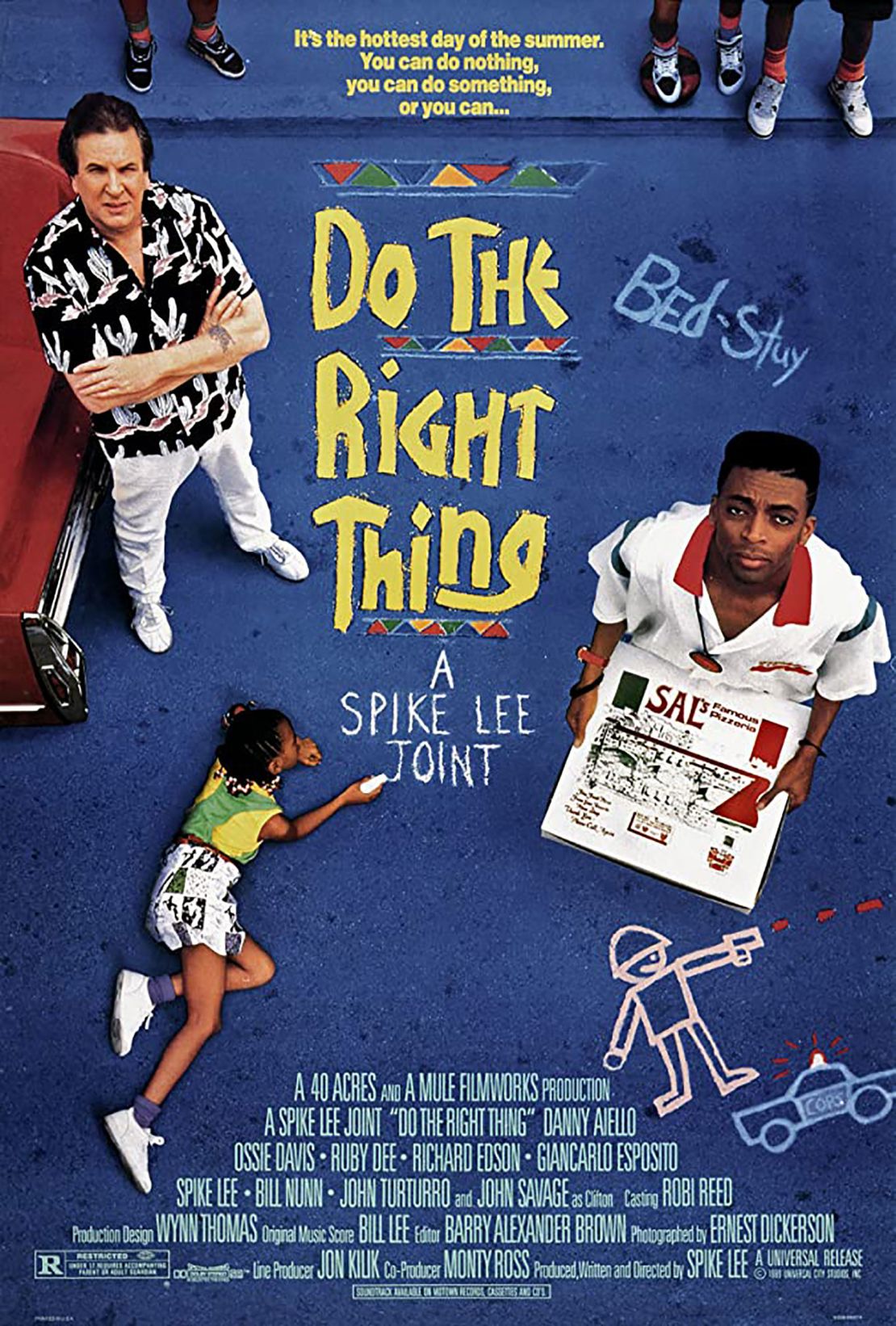

“Do The Right Thing” (1989)

New York’s police force also played a critical part in Spike Lee’s infernal of race, class and power in 1980s Brooklyn. Dedicated to the families of several black city residents who have died at the hands of police officers, including Michael Stewart (killed in custody in 1983 after graffitiing a subway wall), and Eleanor Bumpurs (shot twice a year later while being evicted from her public housing apartment), this controversial classic established Lee as a major director and unofficial spokesperson for the African American community.

He wrote, starred in and directed “Do The Right Thing.” The film, which is set up like a play featuring a collage of different voices, tries to show how unchecked racism and xenophobia can fester within a community because of economic inequality and intense social divisions. We get a parade of confrontational scenes between the multi-ethnic cast, which included Danny Aiello, Giancarlo Esposito, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee and Rosie Perez in her first role, all doing vivid characterizations.

The premise is simple: a slice-of-life film set on one block on the hottest day of the year. The climax is a neighborhood riot, triggered by the killing of a black man by the NYPD. The images of Brooklynites clashing with police and vandalizing a storefront look like they could’ve been ripped from the current protests. The soundtrack is Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” which plays throughout the film.

On June 1, Lee, who won the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar in 2019 for his film “BlacKkKlansman,” posted a short film on Twitter called “3 Brothers” (he debuted it on a CNN special report with Don Lemon), that intercuts cameraphone footage of Eric Garner (a police officer was accused of Garner’s death after choking him in 2014), and George Floyd, with a scene from “Do The Right Thing,” in which Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) dies in a police chokehold. The short starts with the words, “Will History Stop Repeating Itself?”

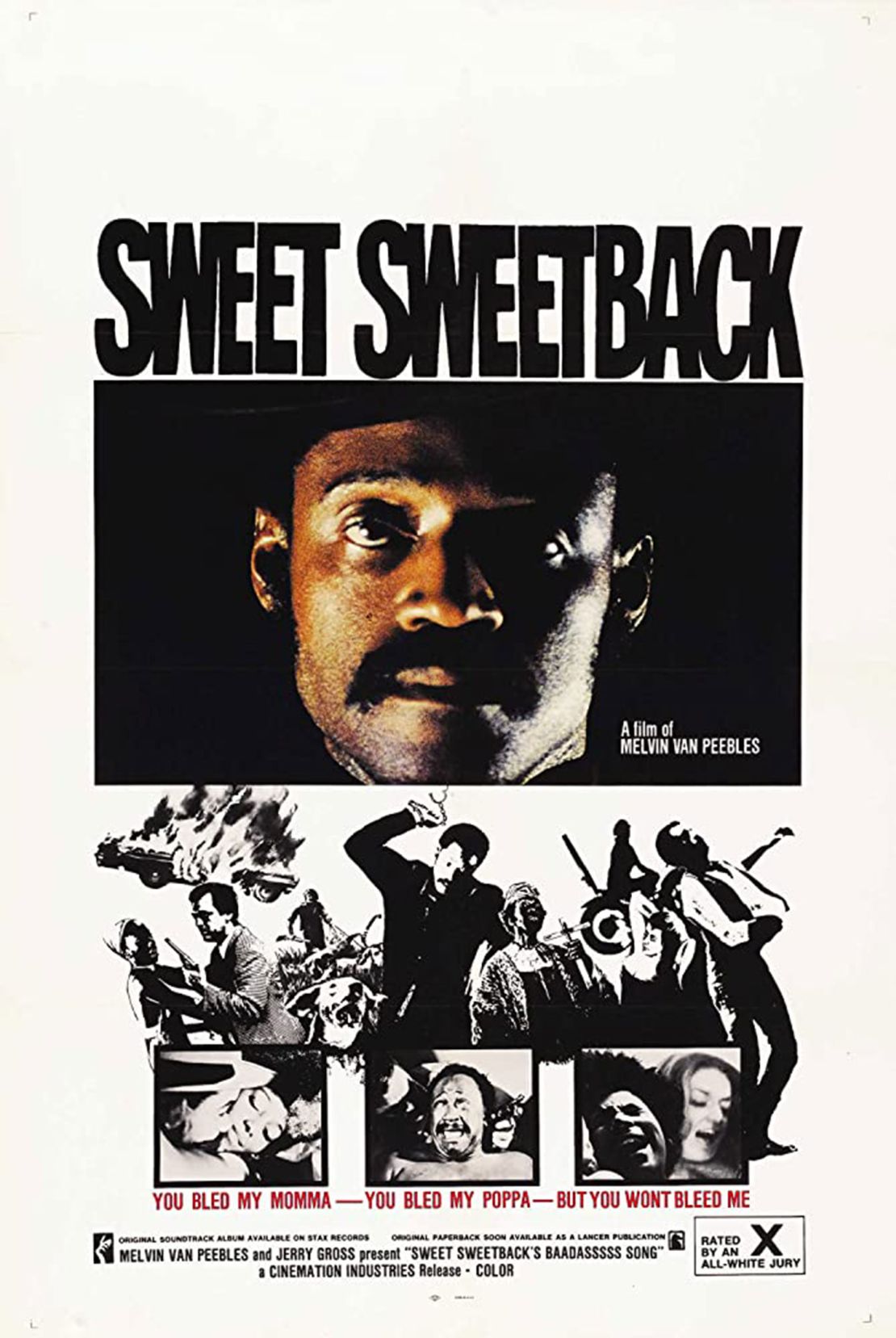

“Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (1971)

Many of the people who have turned out in droves at recent protests have expressed their anger at police violence – some have themselves clashed with baton-swinging police or have been tear-gassed or hit by rubber bullets – and they are ready to take action. That’s the kind of story Melvin Van Peebles set out to tell in “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song,” a scrappy independent film from 1971 that made a then-impressive $10 million at the box office.

The tough but silent protagonist here is played by Van Peebles, who also served as writer, director, composer and editor. In sharp contrast to previous black stars like Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte (whose characters were often neutered), Sweetback is a sexual dynamo with the ladies. For the first ten minutes, the film feels flamboyantly risque. Then Sweetback becomes radicalized – has a full-on political awakening– after witnessing two white officers brutalizing an innocent black militant. He intervenes, saving the brother, but kills the cops in the process. At that point the film begins to feel like a Molotav cocktail to white authority.

“Van Peebles’ film was groundbreaking for its depiction of Sweetback’s blatant sexuality, which poses a threat to the system,” said film and TV producer Stephanie Allain, a longtime advocate for equity and inclusion in Hollywood, and whose credits include “Dear White People” and last year’s Oscars telecast.

“But his cop killing separates him from society and puts him on the run, probably forever. To me, it’s a statement that black male strength is frightening to ‘the man.’ And it still is.”

“Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” was the first movie to reflect the politics of the Black Arts Movement, one tenet of which is for black people to promote empowering images of themselves in the media. And with its funk-soul soundtrack and shots of the black community aiding Sweetback, as he runs for his freedom, the film also seemed to hint at a grassroots revolution in cinema. It was, and it wasn’t.

While Van Peebles did introduce a defiant new hero who triumphed over a brutal white power structure, paving the way for the blaxploitation era of the 1970s (which at its unprecedented peak saw more than 40 black-themed movies produced over a two-year span), few films since have matched its cultural resonance.

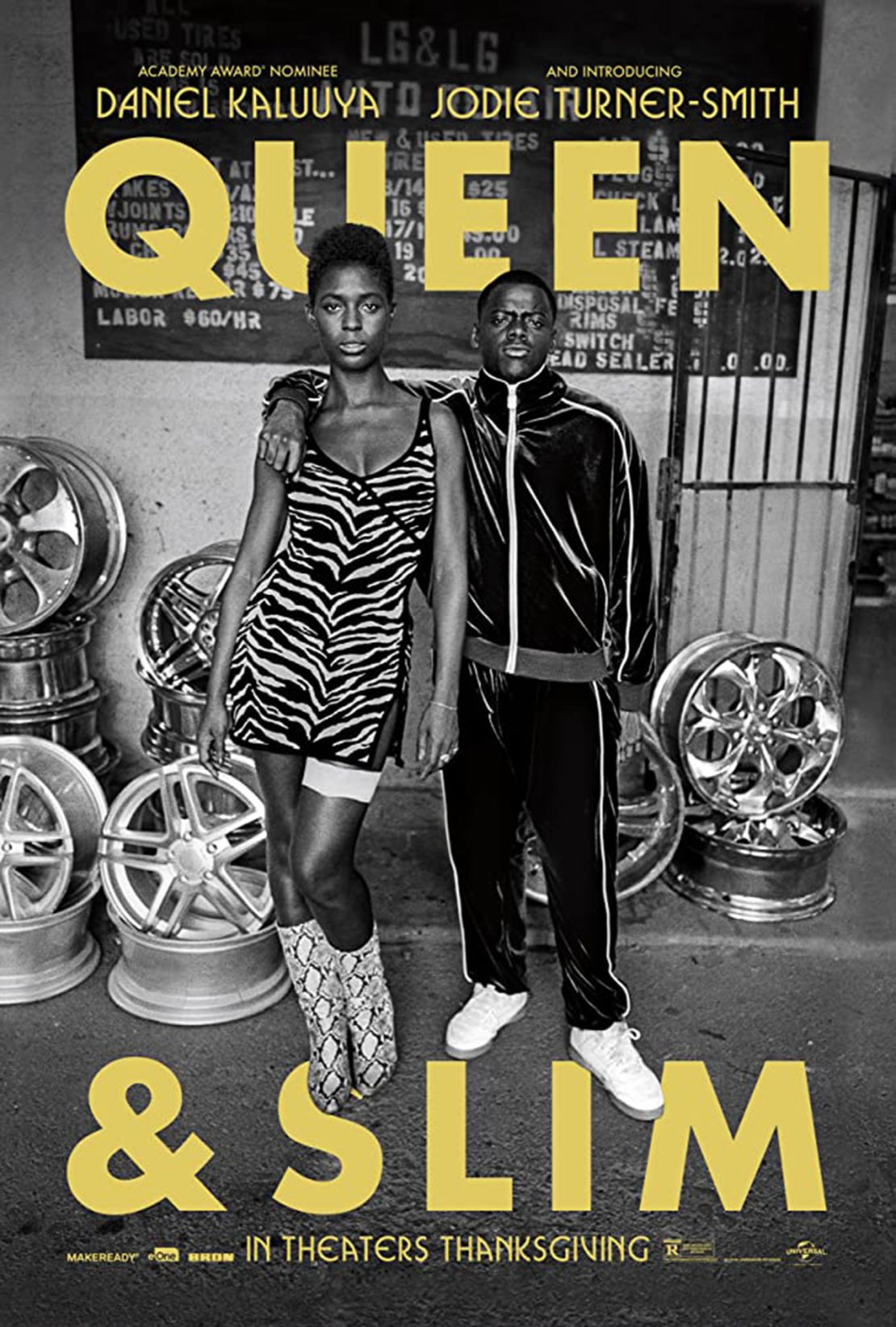

“Queen & Slim” (2019)

If Sweetback had any offspring they would be “Queen & Slim.” The title characters in this intriguing drama from 2019 start out at an Ohio diner, where they are on an awkward first date. She (Jodie Turner-Smith) is a black defense attorney; he (Daniel Kaluuya) works at Costco. While heading home their car is arbitrarily pulled over by a racist police officer. A scuffle ensues and they shoot and kill him in self-defense. Shell shocked, they flee the scene.

The comparisons to “Bonnie and Clyde” are unavoidable. (“Well, if it isn’t the black Bonnie and Clyde,” says one of the characters.) Like that classic about the real-life, white, Depression-era bank robbers, “Queen & Slim” has outlaws who fall in love while eluding the authorities and become accidental folk heroes, in this case, because of a viral video of the officer’s dashcam footage.

But whereas the thrill-seeking and sex-starved antiheroes in “Bonnie and Clyde” were excited to see their pictures in the paper, Queen and Slim are just the opposite. They are on the lam because of the same police abuse and systemic injustice that have ignited the current protests.

By making a terrifying menace out of what is assumed to be a protective force – the police – the filmmakers have created an audacious, lyrical film that should be required viewing for anyone who wants to understand the grief and rage of the Black Lives Matter generation.

“Queen & Slim” was the work of director Melina Matsoukas, a young woman of color on the rise whose stylistic music videos for Beyoncé have mixed documentary and fantasy elements, and “The Chi” TV series creator and LGBTQ activist Lena Waithe, who called her original script “protest art.”

The filmmakers said the goal with “Queen & Slim” was to realistically portray what it means to be African American today, where you feel the need to regularly contemplate your own mortality, in hopes that you don’t become the next hashtag, while following your own path to happiness. One criticism of the movie, however, is that it might be a little too real, or not optimistic enough anyway.

“‘Queen & Slim’ was very powerful and effectively communicated the psychological and emotional conflicts that exist within the black community toward the police,” Dr. Umar Johnson said. “On another level, I feel that the movie did a disservice to the black liberation struggle by not allowing the two protagonists to escape. It reinforced the idea that we can never successfully revolt against the white police power structure.”

That may be what the film says, but then, new scripts are being written every day.