The body of Salamatu Jalloh lies on a straw mat on the floor of a small, earth-colored room. After the 13-year-old died, police warned villagers not to bury her before a post-mortem could be carried out. But four days later, in the scorching heat, the corpse continues to lie here, tightly wrapped in a blue and pink cloth, a foot poking out at one end.

“Open the windows,” says a police officer wearing a white surgical mask, as he enters the room. The smell is suffocating. A swarm of flies buzz incessantly over the girl’s face, disrupting her temporary resting place.

The short dirt road through the village of Kabilor, in Kambia district, northwest Sierra Leone, is largely deserted. Villagers watch solemnly from stoops in front of their mud-brick homes as the police arrive back at the scene, this time accompanied by CNN, the young girl’s father, and a well-known activist, Rugiatu Turay.

“Seeing her decomposing body with flies all over it, and the smell leaves me devastated,” says the father, Mohamed Jalloh, crying inconsolably.

Local police tell CNN that Jalloh is believed to have died from excessive bleeding in the Bondo bush – a place where a weeks-long secret initiation and rite of passage into womanhood (and into membership of the Bondo Society) takes place. In Sierra Leone, this initiation begins with Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) or Female Genital Cutting.

Jalloh’s mother and grandmother took her to the initiation, the officers say. They have now been arrested, along with the Sowei, the woman who leads the ritual and performs the crude operation.

Her father is furious. “I never wanted my daughter to go through Bondo. I am opposed to it,” he says. “I was never informed about it. They just did it on their own. All I was told was about her death and her dead body.”

When the call came about a dead girl, CNN had been meeting with Turay in her hometown about an hour south of the scene. She is the founder of an organization working to end FGM in Sierra Leone not simply by decrying its harms but by recognizing the value of ritual and offering the community an alternative rite of passage. As a result, she is well known by local anti-FGM activists who alerted her to another tragic death.

“The lifeless body of Salamatu has been here for almost five days and nobody cares,” Turay tells CNN with tears in her eyes. “Whenever I hear that somebody – a child or a woman — died because of FGM, I feel so devastated, I feel so broken. We need to continue talking to save others.”

This woman is trying to stop girls' genitalia being cut. But not everyone approves

200 million girls and women around the world have undergone FGM

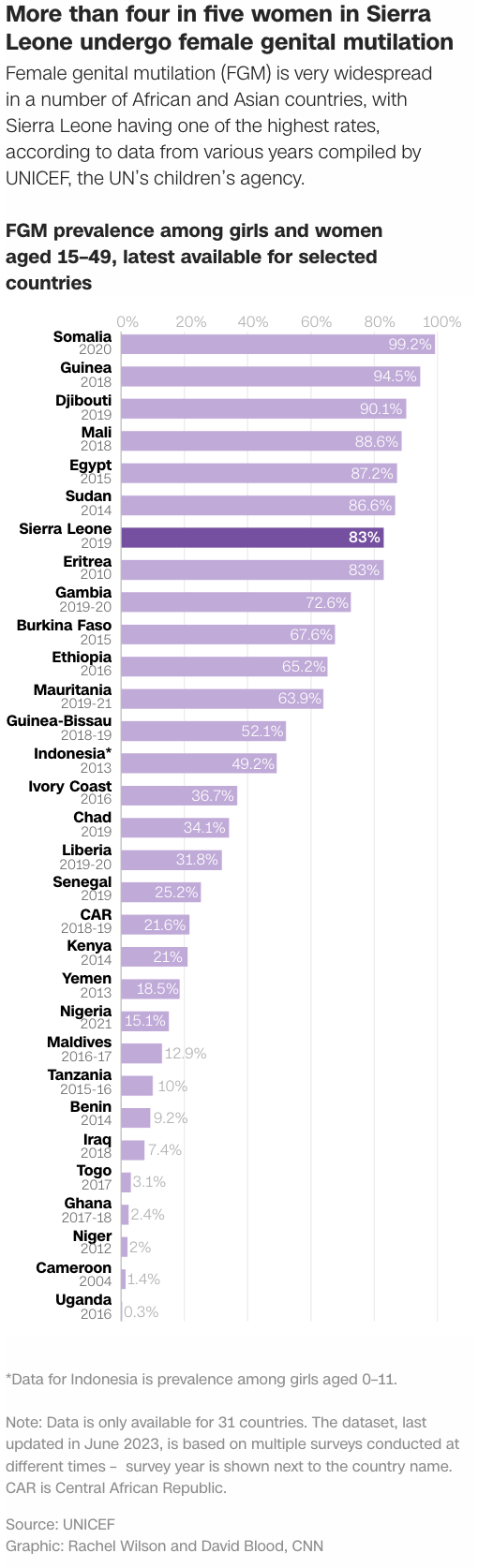

FGM involves the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia. There are differing numbers from various UN agencies (due to inconsistent data collection in-country) about prevalence rates but the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that at least 200 million girls and women in 31 countries have undergone one of four types of FGM. The practice is said to be happening on every continent, though it is most prevalent in the Arab states and in Africa.

While the outcomes from FGM depend on many different factors, ranging from the skill of the practitioner to the hygiene levels of where it takes place and the general health of the girl or woman undergoing the procedure, cutting can lead to a range of complications. These include: severe bleeding, problems urinating, menstrual disorders, infertility, and prolonged labor that can result in the death of the fetus.

Sierra Leone has the seventh highest FGM rates in Africa. According to UNICEF, nearly one in ten girls aged 0-14 have been cut (as reported by their mothers) – though, the agency cautions that “the data on prevalence for girls under age 15 is actually an underestimation of the true extent of the practice” as girls remain vulnerable to FGM until they reach customary age, which is 18 in Sierra Leone. The practice also spans all of Sierra Leonean society: it is done by wealthy and poor people, urban and rural, across religious groups and educational levels.

It is impossible to know how many girls and young women, like Jalloh, die every year in Sierra Leone after undergoing FGM as the Bondo Society is shrouded in secrecy, and silence is maintained through superstition and fear. A 2017 report into Bondo by Forward a leading African organization working to bring awareness on FGM, revealed that “even talking about the Society, women believe, puts them at risk of ‘curses’ and ‘demons’.”

Passion born from experience

Every week, Turay and her team at the Amazonian Initiative Movement (AIM) receive calls about suspected FGM deaths from local activists who are part of a countrywide network called the Forum Against Harmful Practices. Then they turn up at the scene, in an attempt to prompt police forces to take action. From Turay’s experience, if no fuss is made, a girl is given a hurried burial, the cause of death never investigated, justice never sought, lessons never learned.

Turay’s passion to end FGM was born of personal experience. As a young girl, she’d always loved what she’d known of Bondo — the singing, dancing and celebration — but she remembers her mother telling her things like: “Never let someone touch your vagina,” and “The day you go to Bondo, you’ll know what Bondo is.”

That day came when Turay was 11. Her mother had recently died and she was asked to join her elder sisters at an aunt’s who lived across town. “They said ‘your auntie wants to see you and she has prepared food,’” Turay recalls. “While we were going, somebody grabbed me at the back and they stripped me naked.”

Her mother’s voice ringing in her head, Turay says she “put up a strong resistance,” but was blindfolded as several people pinned her down. She tells the story in disjointed vignettes as people who have endured traumatic events often do: “Then I felt the sharp cut. I started fighting and when I woke up, I saw my sisters, the two of them on the floor, bleeding. Just two days later, I started bleeding excessively. I could not walk for seven days because I lost so much blood.”

At the end of the 14-day initiation, the girls returned to school. Like all who have been initiated before them, they were expected to keep the reality of what happens in Bondo Society secret, but Turay resolved to tell her friends about what she’d endured. Also concerned about her wound which had become swollen, Turay told her father as well. She would spend three months in hospital recovering from the infection.

It wasn’t until 2000, two years before the end of Sierra Leone’s brutal civil war, that Turay’s desire to reveal the truth about FGM started to take shape. While in a refugee camp in neighboring Guinea, she met other survivors of FGM and formed the AIM. Many of those women later sought asylum and moved abroad but Turay was adamant about returning to Sierra Leone and soon went into politics. At the height of her political career, in 2016, she was Deputy Minister of Social Welfare, Gender and Children’s Affairs.

“It was out of my experience that I decided to speak out as a survivor to make sure I protect other women,” Turay says. “There are a lot of girls dying silently.”

Today she works full-time on AIM, supported by a staff of 20, their work funded by donations from within Sierra Leone and abroad, including aid from the German government.

Preserving culture, removing cutting

Campaigners say that the prevalence of FGM around the world has been falling for 25 years (though individual numbers may be rising because of fast-growing populations) but in Sierra Leone, part of the reason the practice has remained entrenched is because of the limited power it gives to initiated women in a society where they are otherwise, largely powerless.

The 2017 Forward report into Bondo put it this way: “Initiation into Bondo is seen as necessary for the progression of women, in terms of their own self-worth and worth to the community. In a poor society where girls face such hardship, Bondo is one of the few times in their lives when girls are celebrated and at the center of attention.”

Turay recognized that for many women, Bondo Society was about empowerment, and knew even from her own experience that inside the Bondo bush initiates were taught life lessons, such as how to cook and how to look after a family.

So, in order to preserve what is special about Bondo and abandon what’s harmful, in 2016 she decided to start an alternative rite of passage. “Everybody looks at Bondo as FGM, FGM as Bondo, and you have people arguing that if they are not cut, then it’s not Bondo,” says Turay. “So, our work is to make sure they understand that the two can be separated.”

The ‘Bloodless Bondo’ lasts 14-days, like the traditional ceremony (though not all are that duration). In keeping with tradition, the bush remains a sacred place, where young women bond with their peers and learn life skills. However, Turay’s alternative is only held during the school vacations and only girls over 18 can take part, to ensure autonomy and responsibility.

Five years since she began by asking a group of Soweis to make a public declaration to stop cutting and lay down their knives, around 200 young women have now been initiated without being cut.

For now, Turay and the team work in seven districts of Sierra Leone’s 16 districts, holding educational sessions in villages, often hosting discussions, sometimes showing a graphic documentary, because “seeing is believing,” Turay tells CNN. Everyone’s invited: the Paramount Chiefs, who are the custodians of local customs and grant licenses to the Soweis; fathers, mothers, girls and the cutters themselves.

The Soweis have traditionally wielded political as well as cultural power, but as Bondo has become increasingly commercialized, with families reportedly entering into debt to initiate their daughters, Soweis are also growing in economic power. So, it’s important for AIM to find alternative sources of income for cutters.

Kadiatu Bangura made her living as a Sowei. “I was very fast,” she tells CNN, claiming she could cut 25 girls in just minutes. But she adds, “the bleeding I saw going on never left me in good conscience. How could I cut children and then come home and see my own children?” she asks, referring to her daughter who asked not to be cut at the age of 12. Instead, when the young woman turned 18, she took part in Turay’s 2019 alternative initiation, and her mother decided to put down her blade for good.

Now, Bangura says Turay’s organization has provided skills training for former Soweis in her village so they can find new jobs in farming, soapmaking and sewing. In other villages, Turay’s organization has built schools and helped women start savings associations.

Facing criticism

Not everyone agrees with Turay’s methods or her message.

“Let her come and sit with us and discuss what is the reality,” says Dorris Fambulleh, “But if she continues to go about to say whatever she likes, she will be disappointed.”

Fambulleh, Secretary General of the Southern Region Sowei Council, denies that FGM takes place during the initiation rituals. She tells CNN that it is instead Turay who’s using Bondo for personal gain, saying: “All her focus is: ‘I want to do business on Bondo Society.’”

Turay refutes this. “I am in this because of the passion,” she says, explaining that many of her recent activities have been paid for with the money she received from an award. (In 2020, Turay won the Theodor Haecker Human Rights Prize and was awarded $11,900, worth almost a quarter of a million Leones.)

Nassau Fofanah is a former presidential adviser on gender issues who says she was initiated at 15. She tells CNN she refuses to use the term FGM, saying she does not feel “mutilated.”

“The same way I value your experience of trauma… you should be able to not attack me or anybody if we have a different experience,” she says from her office in the country’s capital, Freetown.

Fofanah believes that cutting should be banned for children, but over-18s should be allowed to make their own choice. To this, Turay argues that even at 18, it’s difficult to have informed consent when the practice is so secret — coupled with enormous societal pressures that limit the choices of young women. She adds: “If your experience was good, you cannot say FGM is good.”

Sierra Leone’s government has debated legislating against FGM for decades.

Isatah Mahoi, Sierra Leone’s new Gender and Children’s Affairs Minister, says a proposed amendment to the Child Right Act, that would ban cutting for under-18s, should be tabled this year, but cautions that change will take time. “We are looking forward to seeing it come to an end. (But) you prepare communities. You don’t just go and stop a practice in one day.”

In the meantime, Turay remains highly motivated to keep going because of what she’s accomplished so far. “We will climb the mountain and all of us will be at the mountain top to say ‘FGM has ended’ … in our generation,” she states. But the reality is that cutting in Sierra Leone is also continuing—with more tragic consequences.

On the same day CNN is with Turay in Kambia district, she hears that in a village just an hour’s drive away, another young woman lies in a freshly dug grave, having allegedly died during a Bondo ceremony. Arriving at the scene, the victim’s sister tells Turay that 17-year-old Kadiatu Bangura bled after she was cut and that they tried to take her to hospital, but she died on the way. But the village chief, also at the burial site, claims the death was weeks ago.

Standing near the mound of earth where Bangura was buried before the police could even be informed, Turay angrily tells CNN: “The community members are still trying to hide the truth.”

Turay may have not been able to help this young woman in life but perhaps she can secure some justice for her in death. On Turay’s recommendation, the police later ordered the teenager’s body to be exhumed.